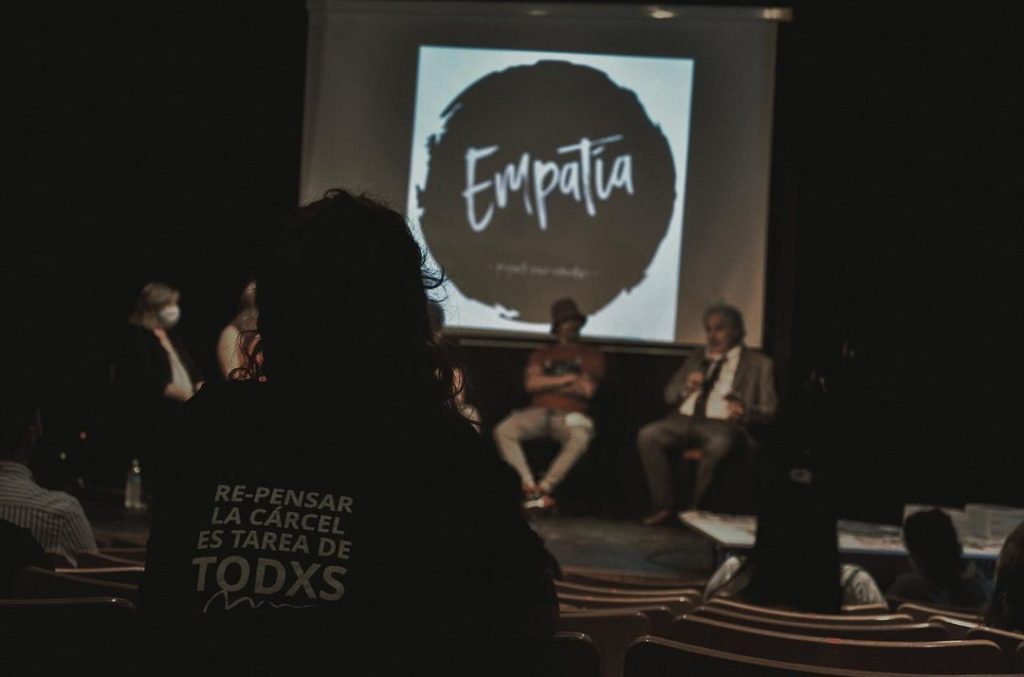

I recently had the pleasure of virtually meeting Rodrigo Ayçaguer, a 23-year-old social work student and coordinator of Proyecto Empatía, with the intention of getting to know more about this essential grassroots project that is trying to change a reality that society has built and put aside.

Proyecto Empatia (Project Empathy), is an Uruguayan grassroot socio-educational project led by young people for young people that are deprived of liberty in juvenile prisons. A week prior to the sanitary emergency declared in Uruguay, on March 7 of 2020, Proyecto Empatia started, hoping to deconstruct the belief of marginalized young people being responsible for the country’s insecurity, a belief that after a wave of attempts to toughen punishments in recent years has been established in the Uruguayan society.

When I asked Rodrigo about the role of empathy in their work since the word is part of their name, I was surprised to find a new way to conceive empathy, not just the typical conception of understanding someone else’s situation but as they call it “critic empathy” that amplifies social and individual responsibility by perceiving yourself as part of the problem and by problematizing the discourses that we legitimize and the realities we help to build.

Realities that are closer than we think and that what divides us from them is just, as Rodrigo said, “an invisible thread.”

The folks at Empatia are trying to go beyond the simplistic take that insecurity is just someone committing a crime but also as a reality where there’s no access to housing, to health care, to education, etc.

THEIR WORK

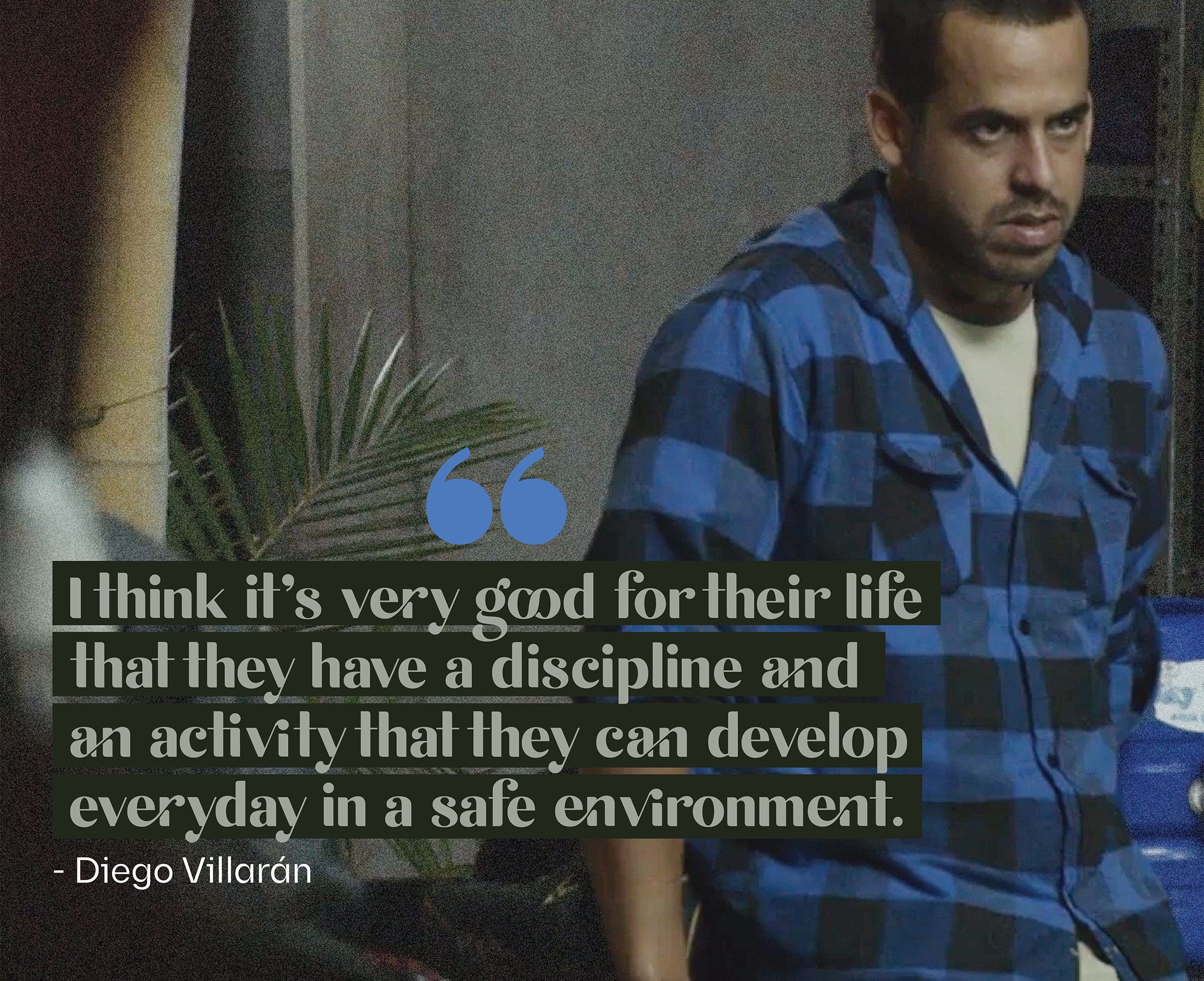

Proyecto Empatia works at the centers of Colonia Berro, where there are 190 out of the 300 teenagers across the country that are deprived of liberty. They impart Communication and Expression workshops aiming to “offer, identify and build skills together.”

These socio-educational reflexive and integrative spaces where they share their life experiences, discuss how they ended infringing the law, and work on the opportunities they can build are well received by the folks at the center. During the workshops, they also contributed writing songs and phrases for T-shirts and sweatshirts that were sold to help cover the expenses Proyecto Empatia faces when imparting these workshops.

“In a world of bubbles, no one wants to poke” and “If there’s inequality, there will be insecurity” were some of the phrases you could read on the T-shirts and sweatshirts.

With the pandemic, the weekly visits were reduced from two to one, with children and older people not being allowed to visit when many of the inmates are parents or their closest ones are older, so these workshops are an escape for them, an escape from confinement and a way to have more contact with people. Their next round of workshops will go from August to December, Rodrigo told me that this time the workshops will feature a more artistic and cultural view.

Proyecto Empatia’s last workshop had the presence of hip hop group AliemRap. Their song below “Es un llamado,” which translates to “It’s a wake-up call,” calls for everyone to seek participation in a social change, to mobilize themselves against hatred and discrimination.

A REALITY THAT NEEDS TO CHANGE

Sometimes when talking about these topics, it all seems to be just a discourse of a certain type of thinking, but the reality where Proyecto Empatia works really does need to change. Fighting against a social construct is hard, and when that social construct has been institutionalized, it’s even harder.

I mentioned, at the start, that teenagers and young people that infringe the law are seen by the Uruguayan society as a “public enemy” when there are only 300 teenagers deprived of liberty across the whole country.

Even UNICEF Uruguay is rolling out a campaign called “Adolescents” after a study found that the Uruguayan society sees teenagers negatively.

These discourses hurt and legitimize places where teens are thrown in with no mental health approach, where violence gets reproduced, where they hurt themselves and social reintegration gets really hard. Where “minorities live in the darkness” as Rodrigo told me when we were discussing how invisibilized and unsafe minorities are inside the centers and how they punish and condemn themselves.

We can’t forget that those who are in juvies, and in the adult system, are people with family and friends, that have or want to have a life project and that sometimes insecurity is the only reality they know.

Thinking of new systems that are not a result of prejudice is possible. As the folks at Proyecto Empatia say, “rethink the prison is a task for all of us.”