I became a certified lifeguard by the Red Cross when I was 14 years old.

The phrase “Emergency Action Plan” (EAP) was drilled into my consciousness. CPR’s 30 compressions to two ventilations ratio morphed into my own muscle memory. I could recite the mnemonic device RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) in my sleep.

During the summers that I spent monitoring patrons and their interactions with the water, I had my tool kit. If I needed to save a life, I could.

My training course taught me that when people are in danger, you don’t question it. There was no blame or judgment applied to those who fell to a stroke or stopped breathing. My goal was to preserve life. Always.

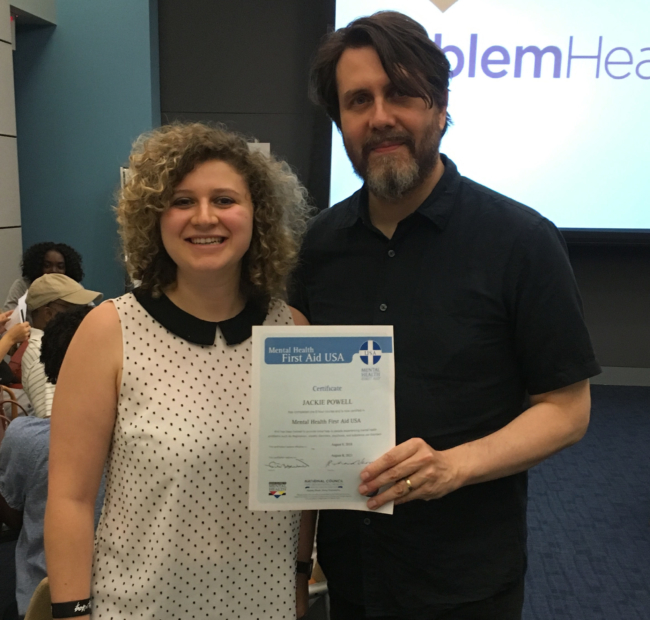

Seven years later on a weekday morning, I found myself surrounded not by rescue tubes, AED machines, and ACE bandages, but instead by chart paper, a plush koala bear named ALGEE sitting on a podium, and a group of 22 people.

The scene had changed, but the goal was the same. I returned to learn how to save lives.

“I want you to think about this course like Red Cross First Aid,” said Peter Gudaitis, the Executive Director and CEO of New York Disaster Interfaith Services (NYDIS), and a certified instructor of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA).

In 2001, Betty Kitchener and Anthony Jorm developed the MHFA Training and Research Program in Australia. Participants become proficient in mental health assessment and referral for various mental health problems including depression, anxiety, psychosis, substance abuse, and eating disorders. The aim is to keep others safe.

A mental health problem is an umbrella term that includes both mental disorders and the presence of symptoms that may not necessarily warrant a diagnosis. A person’s mental health problem could include anything from a Schizophrenia diagnosis to bouts of anxiety.

According to the National Alliance of Mental Illness, a mental health crisis refers to any situation where someone’s behavior puts them at risk to hurt themselves or others. This could impede an individual from being able to function adequately.

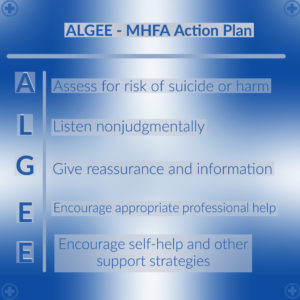

Peter turned to the projector, clicked the remote and an acronym appeared. It read A-L-G-E-E. I looked back at the koala bear and it made sense. ALGEE.

A woman in front of me jumped up from her seat, and scrambled for a photo of the slide containing our new mnemonic. Was I back in lifeguard class?

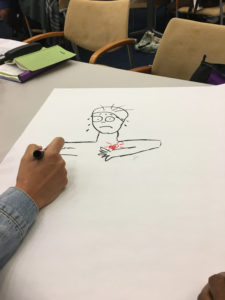

Peter got our attention. He instructed us to draw a person going through an anxiety attack. We needed to understand that there can be physical reactions to an emotional crisis.

I watched as the other participants drew characters. And hanging around the room were distant cousins of Mr. Potato Head and Marge Simpson. The chart paper featured 2D eyes dilating, hearts racing, sweat running, and joints trembling.

Illustrating these characteristics gave us the legs that we needed to be able to identify and assess a situation in the future.

Now, our focus shifted. We were formally introduced to ALGEE the Koala. “You cannot touch,” Peter said waving the plush animal around. “Let’s read through [the acronym] again… loud and in unison.”

A-L-G-E-E.

We were done with art class and moved on to a game of telephone, or so it seemed. All of a sudden, a man was whispering into my ear, but I was simultaneously trying to pay attention to the woman to my right. She was telling me why she enrolled in this course.

I couldn’t focus and was utterly confused. And apparently, my facial expressions and replies showed it.

“Are you even listening to me?” she asked.

The woman on my right couldn’t see that there was a man whispering something in my ear. In that moment, I was impaired. Well, that’s exactly what’s going on for someone who deals with psychosis, a mental health problem which reveals a person’s disconnect from reality. Psychosis is commonly featured as a function of schizophrenia.

One of the participants, Fraiza Gulomikova, an employee at the Pregnancy Crisis Center of NY, thought that this exercise made her reconsider the realities of someone who lives with psychosis.

“I learned that people with schizophrenia are not a danger to the society—it’s the society that can be dangerous to these people,” she said.

Our game of telephone allowed for all of us to comprehend the challenges associated with psychosis. Now we could listen without judgment to those who are most vulnerable.

Richard Vernon, a co-facilitator of my MHFA course and the Partnerships Manager at the Salvation Army, shared his own story. His message was how we ought to be confident, kind, and brave when we come across those who are most vulnerable.

He described a moment where a shirtless man was wailing, screaming, and incoherent outside of his church.

“I came to say goodbye to God,” the shirtless man said.

Richard stepped forward and addressed the man: “I think your life is worth something.”

Following that exchange, Richard reassured his feelings and encouraged him to seek help. The result: a life was saved.

“Your confidence is contagious … don’t be grossed out by someone else’s distress,” Richard said to all of us. “Someone took what he was going through seriously and acted like he mattered.”

Following the story, Richard asked us all: “Would you ever get mad at a kid if they had the flu?”

Then a lightbulb went off, and I finally understood. When I have a fever or achy joints, there’s neither anger nor judgment. But why do we lose our compassion in response to the symptoms of mental health issues?

“We teach kids and adults about the proper diet, how to maintain physical health, but do very little if nothing to promote good mental health,” participant Amy Donaldson said. “Feelings matter significantly. If people had the names of feelings that they have, then they would be able to process their emotions properly and avoid any out of proportion responses such as self-hatred, anxiety, or alienation.”

Over 40 million adults in the United States experience a mental health disorder. There is a common misconception that healthy people cannot be affected by trauma and that mental disorders are symbols of weakness and personality flaws.

Everyone has trauma. Everyone has personality flaws. Everyone has lapses in health.

–

“Who knows ALGEE by heart and can stand up and recite it to the room?” Richard shouted. “If you know it, raise your hand. We are going to stand.”

All of a sudden, Richard was tossing the grey plush koala to himself around the room. He was singing the Nationwide jingle, but substituted the words with the ALGEE acronym. I looked around and there were laughs amidst a sea of confusion.

At this point, the emphasis on ALGEE was becoming a bit redundant. But I later learned that while the repetition wouldn’t end, there was sagacity to Richard’s silliness.

Well, it was our turn. We had to write our ALGEE jingle. Our song choices were all over the map. Destiny’s Child was in the house, as was Rodgers and Hammerstein.

“Why did I get you to do that?” Richard said with a smile. “You are never going to forget the line you just learned.”

–

At the end of the day, we took a quiz that would certify us as official Mental Health First Aiders. We answered questions about hypothetical close friends, family, and strangers who were hyperventilating, exhibiting gloom, abusing substances, and having suicidal thoughts.

The language of the correct answers to the ten questions reminded me of when I took first aid in lifeguard class. MHFA acknowledges tools that I learned at age 14. For instance, putting someone into the recovery position and knowing when to call 911 can play a role in addressing mental health emergencies.

The language which Mental Health First Aiders accumulate is inquisitive, non-judgmental but also guiding.

As a lifeguard, my eyes were focused. My mind needed to be clear. Surveillance required selective listening. As a Mental Health First Aider, my body language, tone, and voice are focused. My biases and judgments are clear. Effective listening is required.

When I have a stomach ache, it’s pretty damn painful, and I want to treat it immediately. During the course, Richard referred to a study which concluded that the average adult doesn’t treat a mental health problem for around ten years. As a MHFAer, I am tasked with narrowing that window.

Walking out of the course, I grabbed my certificate. My toolkit is slightly different. But, my goal is to preserve life. Always.

Learn more about Mental Health First Aid and sign up take a course to become MHFA certified. Also, you can read about the pilot program Teen Mental Health First Aid, which will teach young people in grades 10-12 how to help their peers through mental health crises.