Pink and I have always had a rocky relationship.

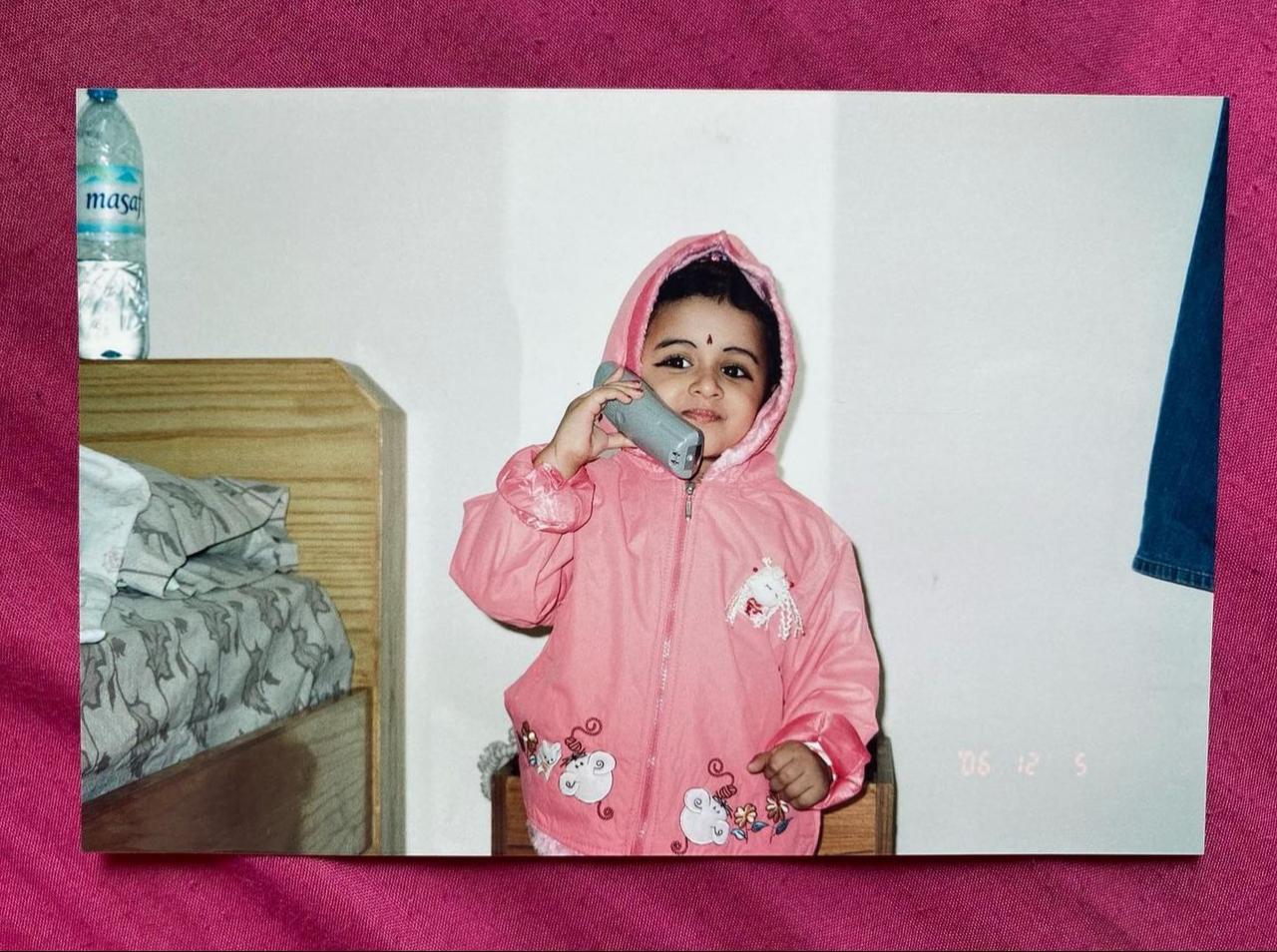

When I was 5, I painted the walls of my world with a million hues of pink.

When I was 9, I told a boy in my class to stop crying because “crying is for girls and girls are weak.” That’s when the thought occurred to me: if girls are weak, and pink is associated with girls, wouldn’t liking pink automatically translate to being weak?

So, I distanced myself from the color. I like black, I said to myself. Black was safe; it didn’t make me a “girly girl” – someone who, in my estimation, was light-headed and airy and weak.

7 years later, I would learn that what I felt when I was 9 and what I told that boy was, in fact, internalized misogyny. I would realize that some of the bravest, strongest people I know are pink-loving, makeup-loving, rom-com-watching girls. However, it took me a while to reach this realization, and for years, I remember struggling to wrest who I really was from this utterly misconceived notion of who I wanted to be. I was in constant turmoil of pink or no pink, boy bands or no boy bands, makeup or no makeup, all while I was a preteen.

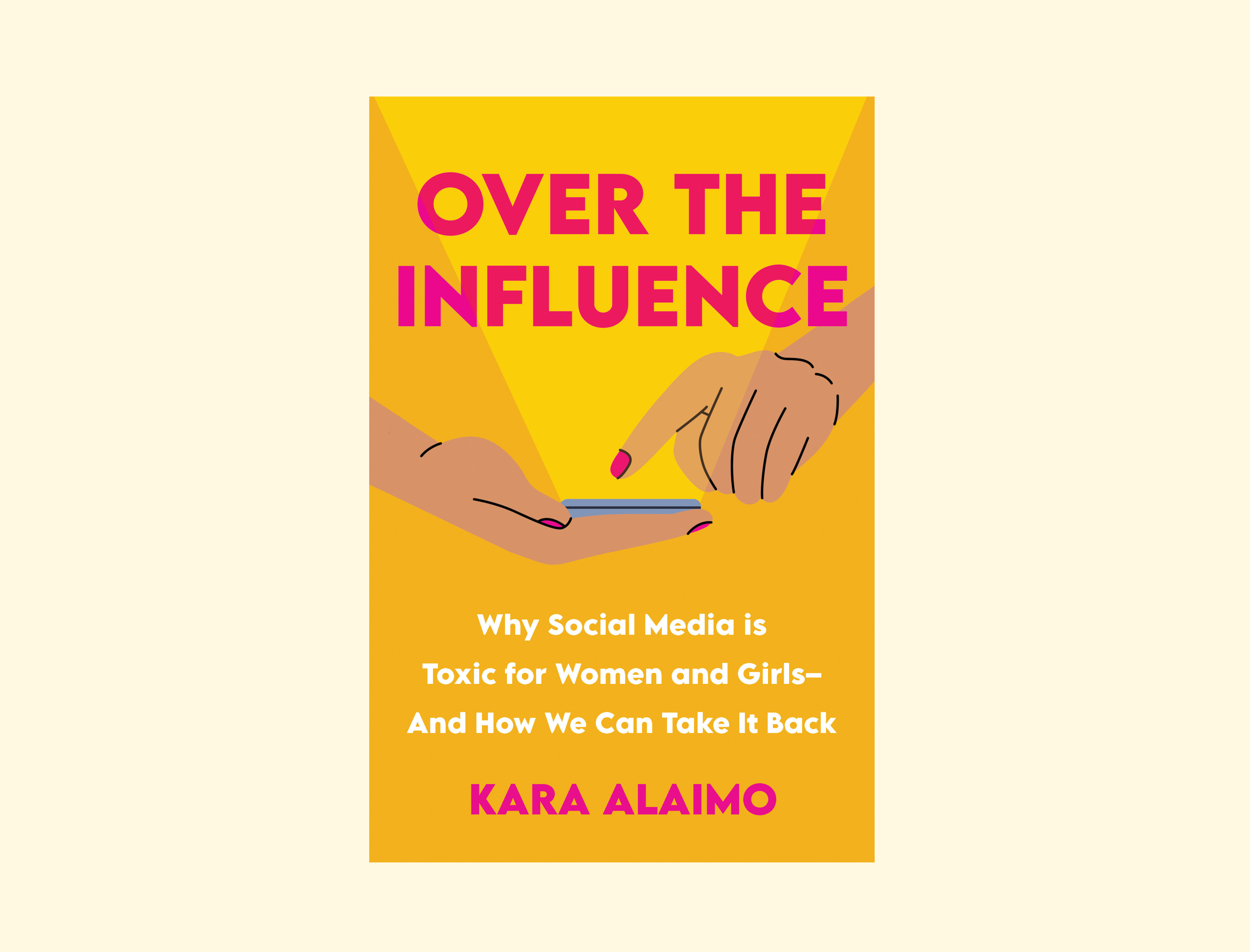

What helped me most in reconciling these identities – and subsequently improved my mental health – was seeing women tell their stories openly and authentically. What stood out, in particular, in this regard, was 2023, which can only be described as the “year of girlhood.” From Barbie to Taylor Swift to Beyoncé, there was so much boisterous celebration in being a girl and embracing every aspect of your personality, “girly” and otherwise. What helped tie a nice pink bow on it was the resurgence of Julia Roberts’ famous Notting Hill line (“I’m also just a girl”) and No Doubt’s bubblegum pink hit Just a Girl on Instagram and TikTok. Coquette core was suddenly trending (see bows drawn on dense calculus problems) and the era of honoring female friendships was finally in.

2023 did more than just heal my inner girl; it sparked real conversations in my circles about female mental health and joy. Women’s stories crept into the limelight through rhetorics on girlhood that were previously used to dismiss them as weak, and this storytelling rippled into the way women chose to express themselves.

This Women’s History Month, we need to make a firmer commitment to listen to women’s stories, and recognize just how much of a positive impact this has on female mental health. We need to infuse these stories with more intersectionality. We need to make the effort to help female stories that spring up from different regions – and not just the West – feel seen and heard. This is, perhaps, one of the greatest acts of service we can do to women’s mental health.

Over the years, my friends and I have remained staunchly united in our love for pink, actively picking apart every stigma we felt was attached to the color. As pink ribbons, earrings, and bracelets accumulate in my jewelry boxes, my five-year-old self has been having a great year, a fact I’m proud of.