Striking findings have emerged from new research conducted by Born This Way Foundation and Benenson Strategy Group about youth mental health, peer and parent relationships, resource availability, and perceptions of community kindness.

Drawing upon recent interviews from over 3,000 youth (ages 15 to 24) and over 1,000 parents, researchers found three overarching themes…

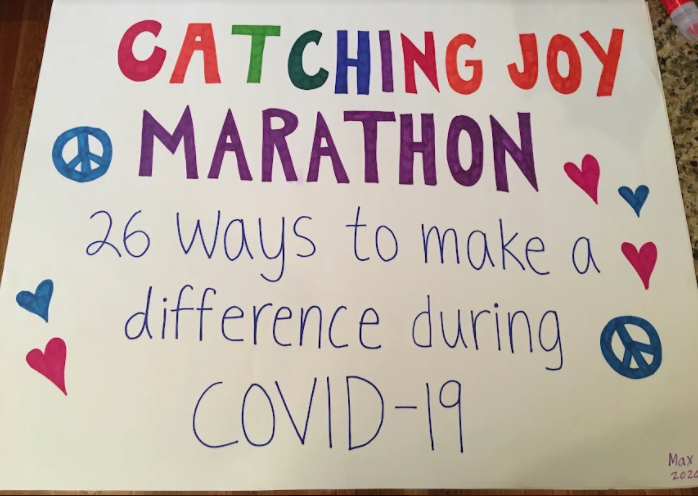

- Kindness in the environment is related to youth mental health.

- Youth identify mental health as a top priority, but also report a scarcity of resources.

- There is a disconnect between young people and parents, especially on issues of identity and mental health.

Compared to people of other age groups, teens and young adults are especially attuned to their social environment. Consequently, living in an environment perceived as hostile or unkind can have particularly detrimental effects on youth.

It comes as no surprise, then, that youth who scored high on mental health status also reported a kinder school or work environment. The opposite was also true. This trend persisted across high school students, college students, and working youth, though high school students were most heavily impacted.

How should we interpret this? Are happy kids simply overestimating how kind their school is, while sad kids underestimate it? Or are there a lack of resources contributing to mental health and a climate of kindness?

The newly released research, and current economic climate, favors the latter explanation. Youth who reported a lack of social (e.g., “Teachers say ‘hi’ to students when students get to school”) or institutional (e.g., “There are free mental health/counseling resources…”) resources reported feeling less empowered to change their community and reported it as less kind.

It isn’t simply a matter of youth perception, either. School-based programs like the arts and physical education (both of which youth described as important ways to take care of mental health) have already been cut from many schools nationwide. According to an APA report, mental health personnel, such as school psychologists, are also facing cuts.

Researchers also found a general trend of disconnection between youth and parents. Youth were more likely to turn to their friends to discuss body image or having unprotected sex, but more likely to turn to parents to discuss a medical diagnosis, physical bullying, or sexual assault.

In other words, youth seem comfortable discussing traumatic experiences with parents, but not the day-to-day issues of identity and sexuality that all young people go through.

Parents also overestimate how likely their children are to talk to them about a number of issues, how kind their child’s community is, and how stressed their child is feeling.

While it’s a good sign that youth feel comfortable approaching parents about trauma, they should also feel comfortable discussing issues of identity, sexuality, and mental health. Parents have more life experience dealing with such issues, and often live with their children, making them an ideal candidate for having these conversations.

Broadly, the new research can be summarized in a few short phrases: kindness matters, mental health matters, and communication matters.

With this new information, what do we do next?

A friend and fellow activist once told me, “There’s a difference between advocating with a community, and co-opting a movement.”

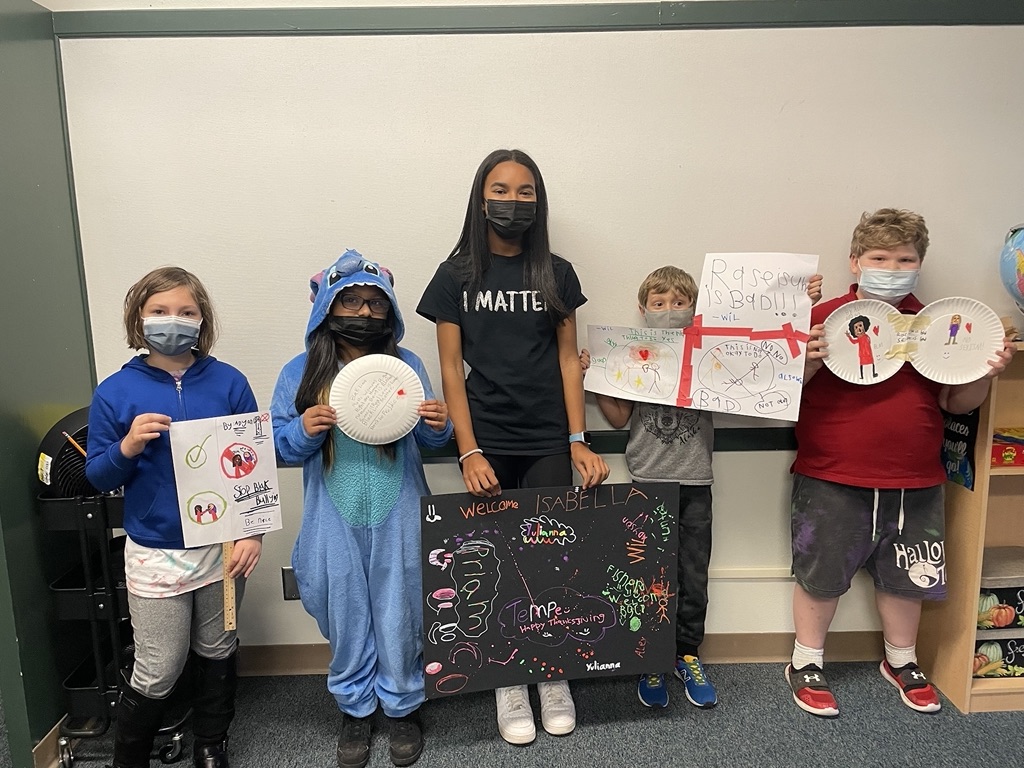

If this research demonstrates anything, it’s that young people know what the problem is and what their needs are. They prioritize mental health and kindness in communities. They are aware of the lack of resources available to them. They aren’t having the conversations with parents that they might like to have. They are ready to take action.

As adults, we don’t have to do much guessing, and certainly no co-opting.

To all the young people out there, know that we have heard you and that your needs are important to us. We are ready to advocate with you!