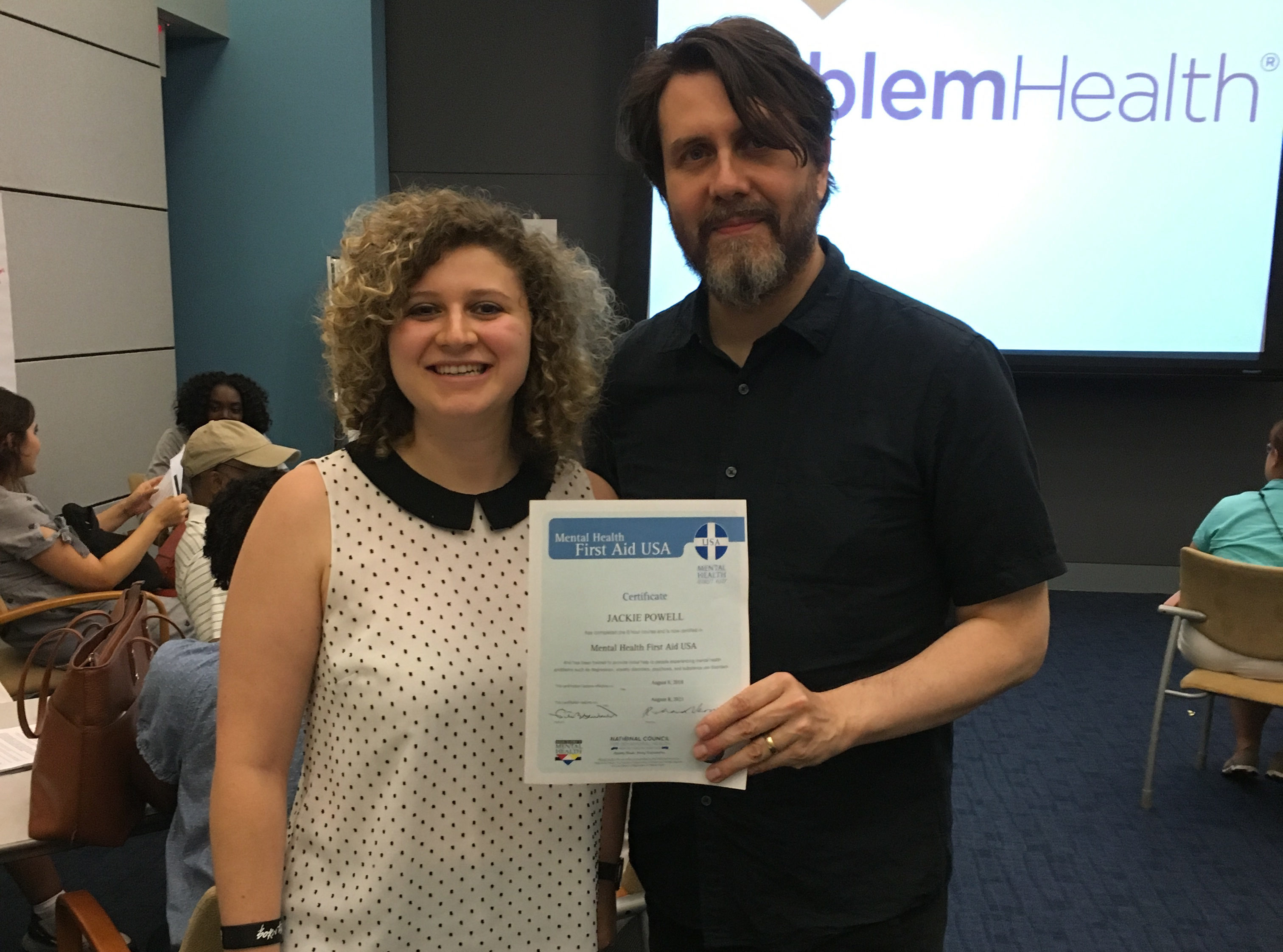

I recently spoke with Jake Sidwell for Channel Kindness Radio about the intersections of mental health and disability. In talking about our experiences navigating chronic pain and illness, we were able to build an environment of solidarity, comfort, and empathy. I hope you feel safe and that your experiences are validated when you tune in as Jake and I share about our mental health and lives!

Please also see the full transcript below:

Voiceover: You’re listening to Channel Kindness Radio.

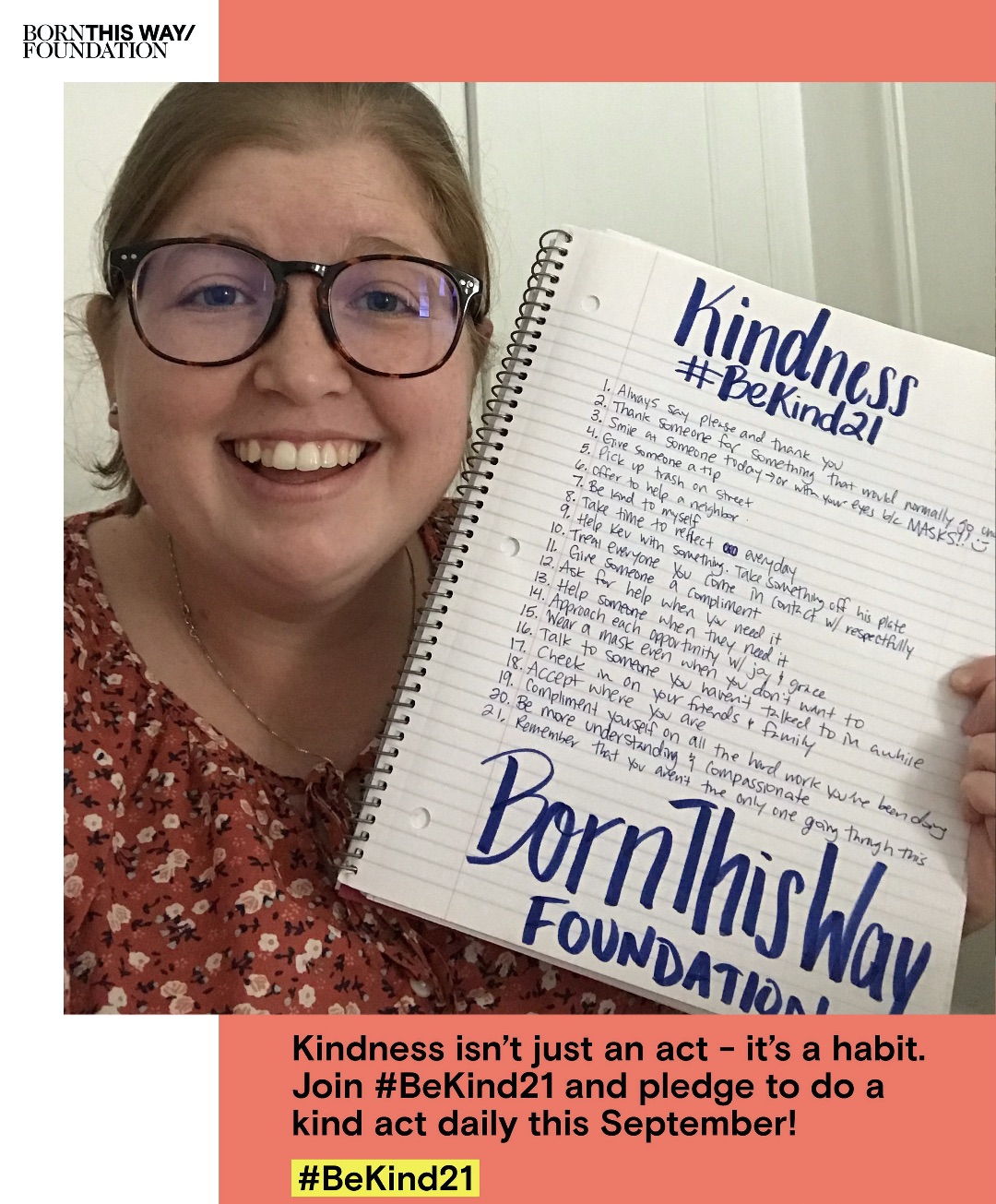

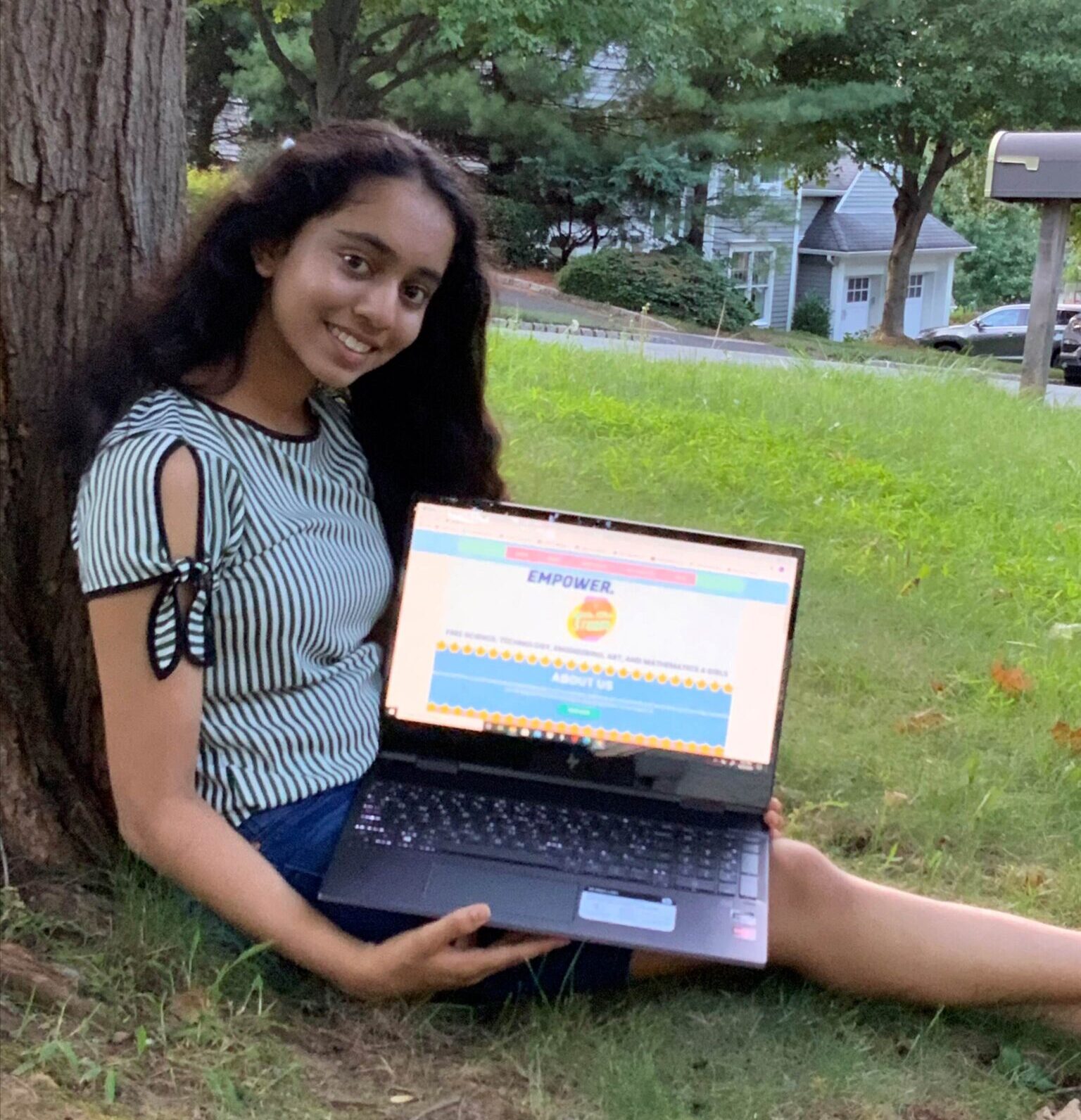

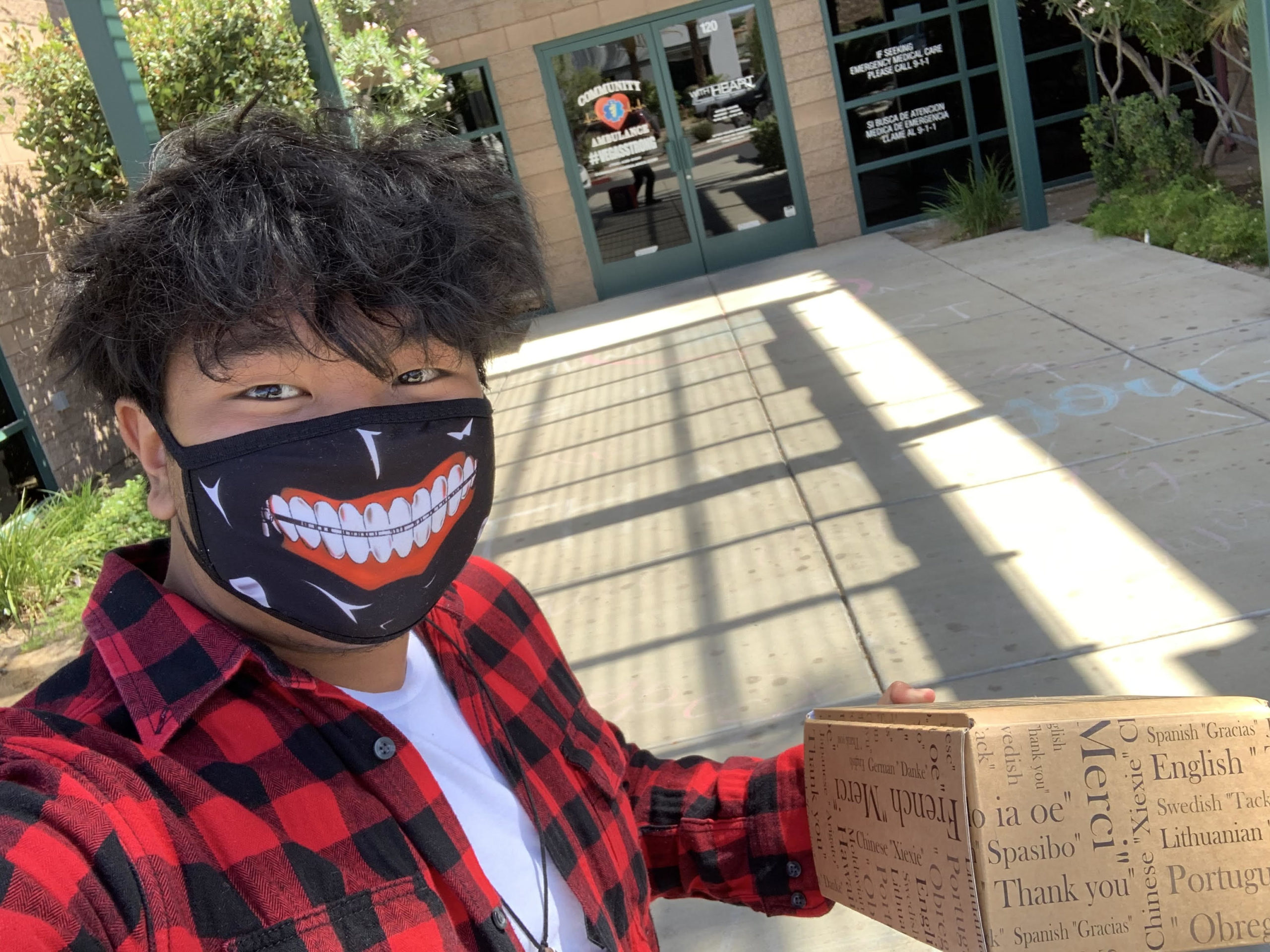

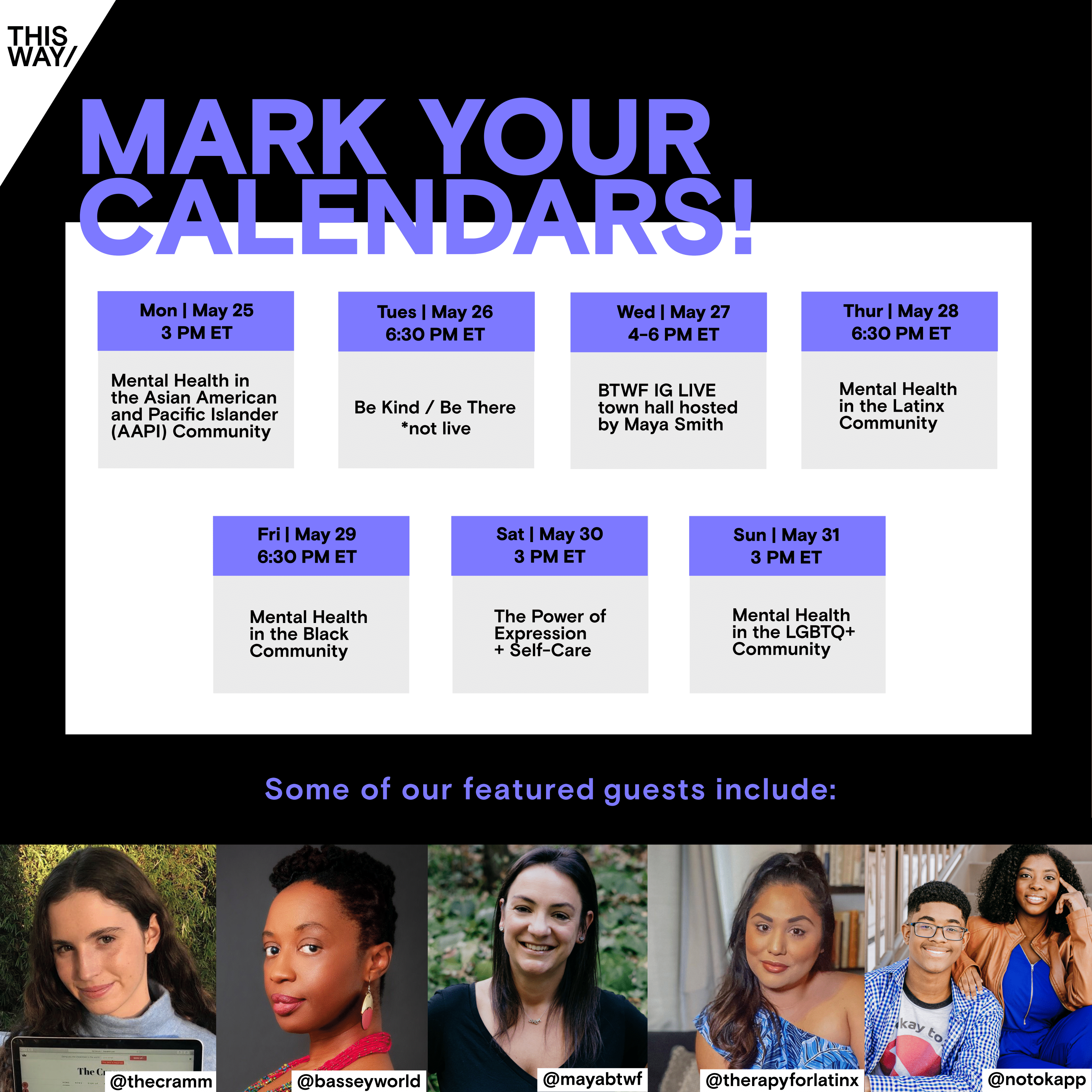

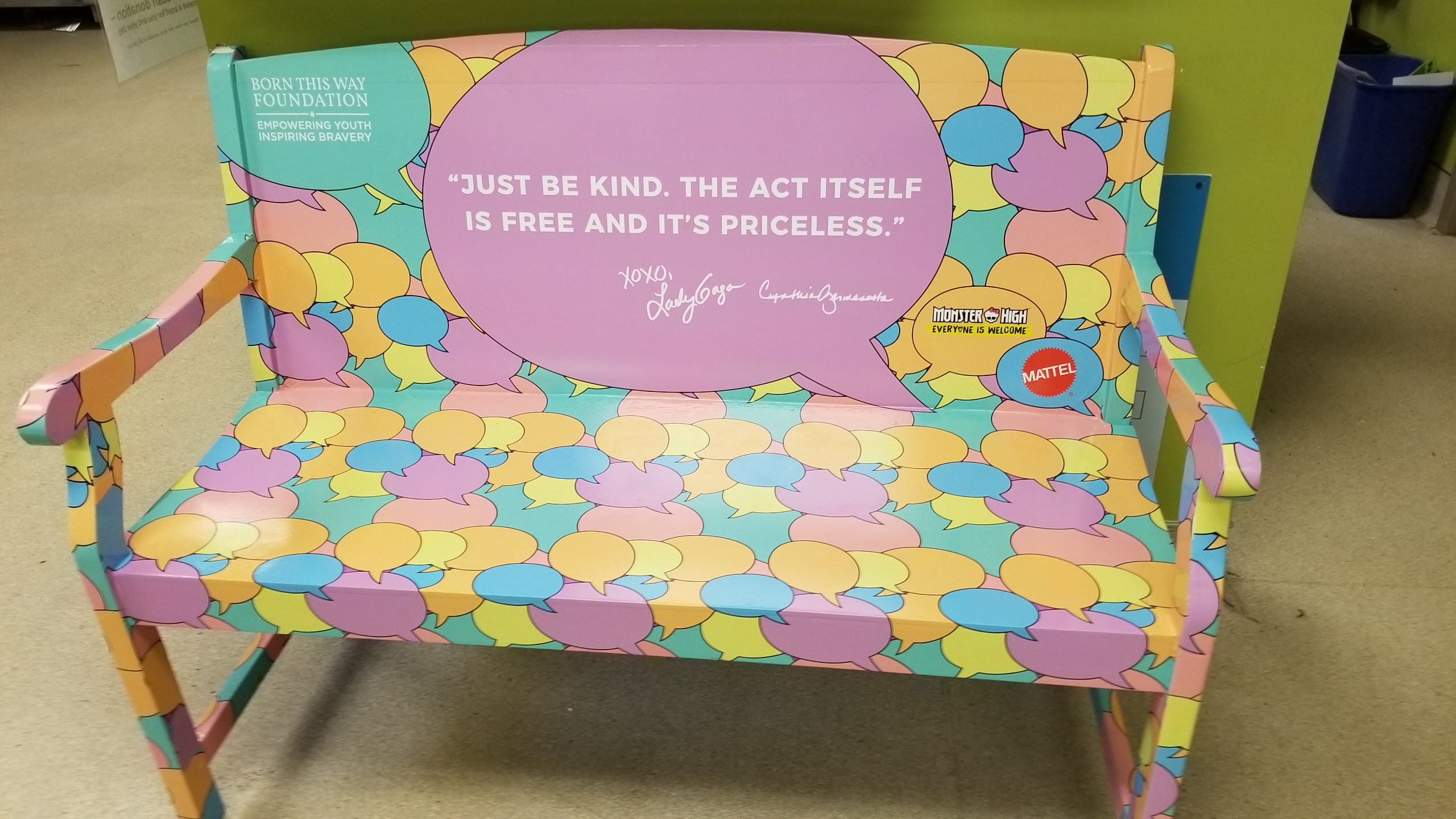

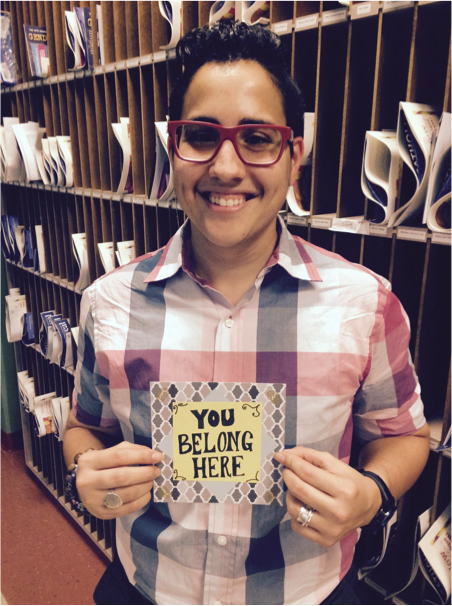

Taylor: Welcome to Channel Kindness Radio. This is Taylor Parker, Program Associate for Born This Way Foundation my pronouns are they/them/theirs, and today I am joined by Jake Sidwell. Jake, I like to start all of these by letting my guests introduce themselves and establish who and how they are in this moment. So why don’t you tell me, who is Jake Sidwell?

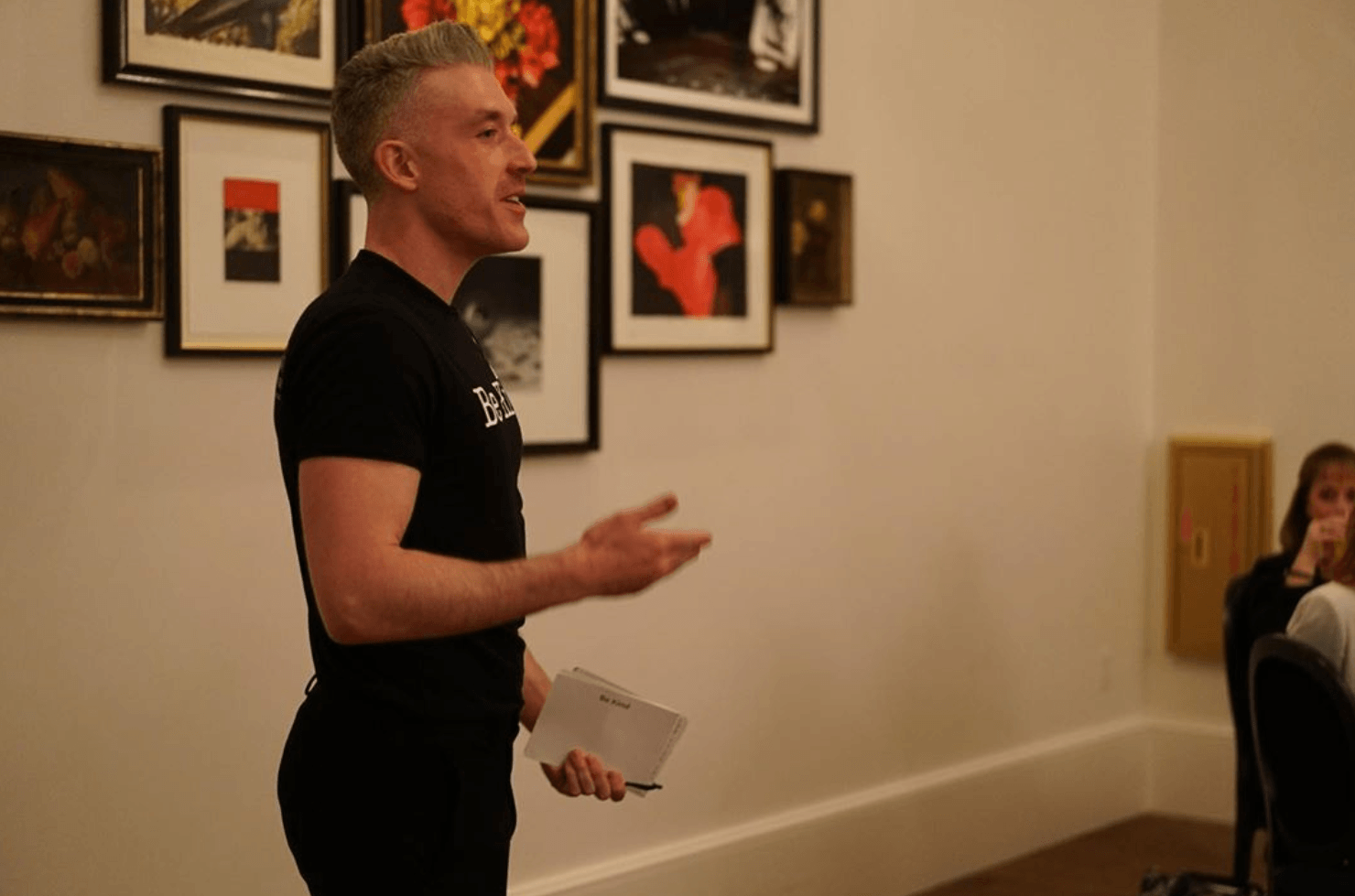

Jake: Sure, yeah, I’m Jake Sidwell. I like to think of myself first as I guess an artist, that’s kind of how I like that’s the lens through which I view the world. Everything kind of filters through that. I’m also a disabled composer – recently disabled within the last five years. Yeah, that’s basically how I view myself and how I like others to consider me.

Taylor: I love that you started with the fact that you are an artist. I love that you are prioritizing your art in this moment and allowing that to flow through how you are asking others to view you and understand you. But that plays perfectly into this first question. So identity is a huge factor in disability and chronic illness and within our community. So what role, for you, has disability played in your identity and why is that?

Jake: Sure. Well, I’d like to start the conversation about that by mentioning how this has been a pretty recent change for me. Most of my life, I haven’t been disabled. I came down with a chronic condition. We’re still figuring out exactly all the pieces to that. But I’m pretty new to the conversation. So I’ve been doing my best to listen since then, because, honestly, a lot of the people who’ve been advocating for people like me for years. The conversations have been ongoing for so long. When I came to the table, most of the work had been done. Obviously, there’s still plenty of work to be done. But what I mean is, I didn’t have to do a lot of advocating on my behalf to be part of the conversation, which I’m really, really thankful for. So as far as like – what was your exact question again?

Taylor: Yeah, so just how does identity or how do identity and disability interact for you? So whether that is your identity as an artist, is that impacted by your disability or has disability impacted other identities within your life?

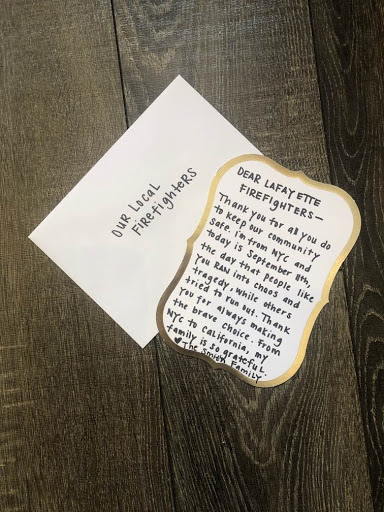

Jake: Yeah, absolutely. It took me a while to even accept a disability as an identity because someone who wasn’t disabled and my sphere of influence didn’t include many disabled people. So my engagement with that community was practically nil. So having to even learn to accept a disabled identity felt like, to me it was a detriment. It felt like it was the wrong way to look at things that maybe I was accepting weakness. And that’s, you know, that’s kind of a lot of the dialogue that’s used around it, that continues to stigmatize it. So for me, it was like a giant weight being lifted off, accepting that the things that I was experiencing the way that I was feeling did not reflect the way that some doctors and some of the public were talking about my own experiences to me. So for me to be able to identify as disabled and to explain that to other people in a way that helps them understand. I mean, it’s like, it’s a night-and-day difference psychologically, like just being able to accept who I am and like, how my identity has been fundamentally changed by my new limitations and having to learn that and, as far as my artistry as well. A few different things have been affected like more recently, I’ve had some moments of recovery, which has been really, really nice being able to sit upright, like right now I’m sitting at my keyboard. I’ve had some moments of recovery where I’ve been able to sit upright and play at this keyboard. But I have behind me here, I think this is an audio podcast. But on the video, there’s behind me this little keyboard on a hospital tray. Well, my wife and her family and some friends and some people, and some anonymous people – I still don’t know who it was who sent me the hospital tray – but helped get me a little setup so I could do all of my music. I do like, scoring compositions for like, short films and little things like that. So I could just do it from bed completely prone, and it was an absolute life-changer, especially in that moment where I hadn’t been playing music for months and months and months, which the first thing I mentioned was that I like to see myself first and foremost as an artist. And so it was really heartbreaking to feel like I couldn’t do that. For people to open up that accessibility to me, was like, it was an absolute dream. Yeah, I couldn’t be more thankful for that.

Taylor: I love that they were able to help you find new ways to still pursue your art in ways that were more accessible to you in that moment, without any sense of shame that was attached to it. To tell a little bit of my own story, so I’ve grown up with chronic illness. I’m 21 years old, I’ll be 22 in just a few weeks. I grew up with chronic illness. Growing up, it was just something that you know, I thought I would have to live with – just take medication for – but I never stopped going, and so I just kept making it worse. And then within the last five years, I became – I like crossed the threshold into disability, and I was completely immobile for a while and it was also just a very sudden life changer for me. So I can 100% empathize with you, in that way of sudden disability not really making the conversation around sudden disability, not really making it something that we can think about long term and we’re just hoping that this is not a part of who we are when embracing it means so much more than we were expecting. But in that vein, what would you say to those who are listening or friends of those who are listening who may still be looking for that diagnosis?

Jake: Sure. When I initially became well, or became ill, and within like, the first couple years, a lot of people experience desperation. For me, it manifested in a bunch of different ways that were almost exclusively unfortunate. And so I know what it’s like to feel completely hopeless without a diagnosis and many people, they don’t understand what it is, what it feels like to get results back that are negative, and to not have a positive experience with that. For a doctor to say, yeah, the test results are fine, you look normal to as many diagnostic tests as we can run, you appear normal. How that cannot be a positive experience for many people who are suffering in ways and degrees that many people can understand. You know, I remember moments of like, hoping that, you know, seeing a hematologist, oncologist like hoping that some tests would come back that would show I had cancer, or that I had somehow contracted AIDS. You know, this isn’t to minimize those illnesses, but to explain that when you know that you are physically ill, and doctors are telling you that you’re well it can be really difficult to manage those expectations, and to be let down when they’re effectively telling you, we don’t know what’s going on, and you’re living in limbo. So I want to say to those people who are still looking for a diagnosis, I’m so sorry that you are experiencing maybe for the first time what it’s like, especially in the American medical system, the fight that you have to do as the most vulnerable population, to do all of the work effectively on your own to try and get a diagnosis. I’m so sorry. You have to deal with that I sincerely understand at the deepest possible level. And yet at the same time, I recognize that as a straight white male in America, like my barrier is pretty dang thin and yet my fight to get there was, I mean, it was tooth and nail, it was hell. So I can’t imagine what it would be like to be a marginalized group and trying to break through that same barrier. You know, I can’t speak to that experience, I have no idea. All I can say is, me, the most privileged in the population, had to fight tooth and nail to get that and yeah, I just express my deepest gratitude for everyone, or my deepest condolences to everyone for having to go through that. And I just ask that you hang on and do as much as you possibly can. And the thing that helped me most more than any doctor I ever talked to, was patient advocacy, other patients who are going through and other people who have been in the chronic illness and disabled communities for years and years and years, do everything that you can to communicate with those people. My first diagnosis that I got that has me upright right now speaking and able to breathe again, kept me out of the ER now for over a year where I was having multiple ER visits every month, were patients that came from patient advocacy, other patients who, collectively now we live in a time where we’ve created this web of all of these people who have information, I’m not talking about just Googling your symptoms, not that that should be stigmatized, either, because doctors are doing the same dang thing. You know, they’re googling your symptoms too. So, you know, we shouldn’t be stigmatizing self-education. But we should also be promoting the idea that creating this giant web especially online Facebook groups, all these patient advocates coming together and talking to each other and communicating their symptoms. I was able to find even just the language to explain to each other and to doctors like to be able to say, this is how I feel in a medical sense. This is what I’m going through. It got me my first diagnosis. So, that would be my number one to you. I mean, there’s a million things that we could say, but my absolute number one to you would be to talk to other patients, find them on Twitter, on Facebook anywhere you can. Google your symptoms and find those Facebook groups and other people. You know, I’m not a super strong believer in medical confirmation bias, especially when it comes to people who are the most desperate because I can tell you even when they were telling me that they thought certain diagnoses might be a fit for me. The ones that I fought for the most, were the ones I ended up having. So believe yourself, you know your body.

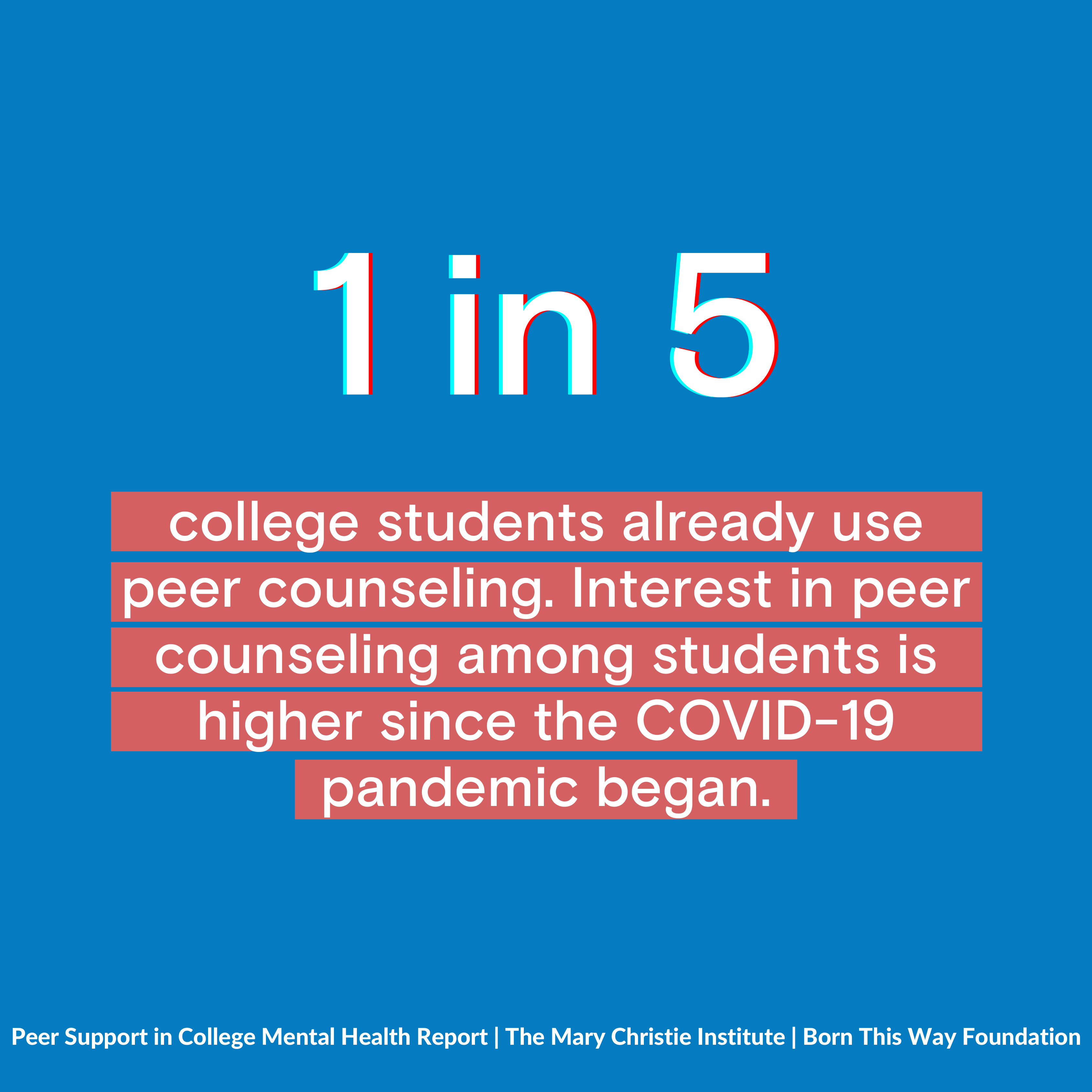

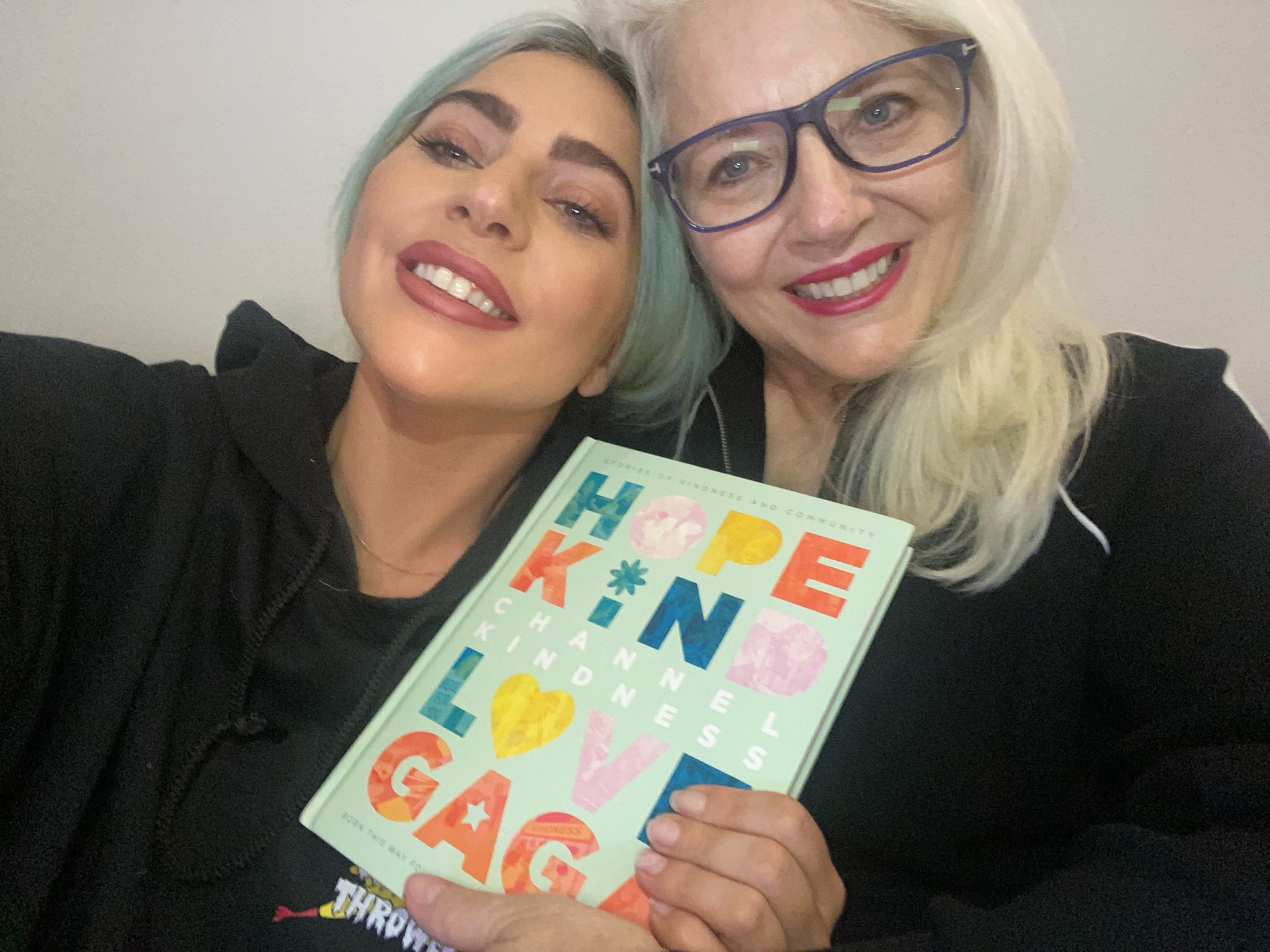

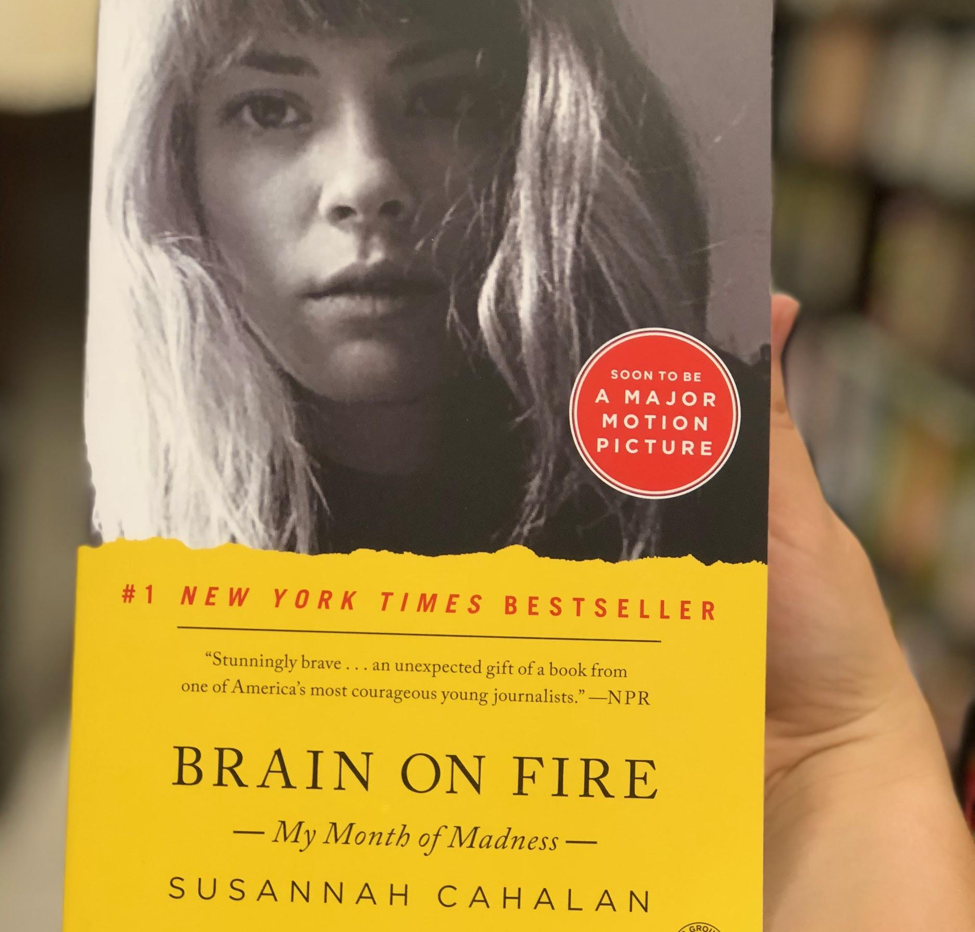

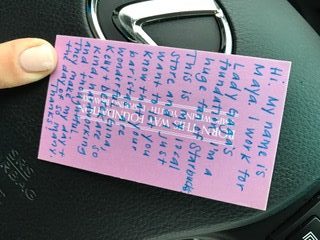

Taylor: That is so, so true. The experiences shared from our community of people experiencing chronic illness are the most life-changing for recognizing your own symptoms because it’s one thing to read it on a website after Googling your symptoms and trying to figure out what this might mean. It’s another to talk to someone and see their lived experience with it. And then see that within yourself. I remember I was already in treatment for other diagnoses when I saw our founder’s documentary on Netflix – Gaga Five Foot Two – not to plug it or anything, but she talks about her life with fibromyalgia and living with her chronic pain. And it wasn’t really until I saw that, that I realized that that wasn’t something everyone else just dealt with behind closed doors. And so I took that to my doctor, and we got a new diagnosis. And since then, I’ve been able to be on a path towards better health. That path may have its ups and downs, but I was able to see that because I was able to see someone else’s lived experience. So what you’re saying is so real and I know that it’s resonating with so many of our listeners. So thank you for your vulnerability in that. Let’s talk a little bit about disability and mental health and how the two interact. So we are coming at this from unique perspectives of people who experience disability suddenly and unexpectedly. But even so, with all that happening, how would you say that your mental health has been impacted by your chronic illness or chronic pain? And how would you say your chronic illness or chronic pain has been impacted by your mental health?

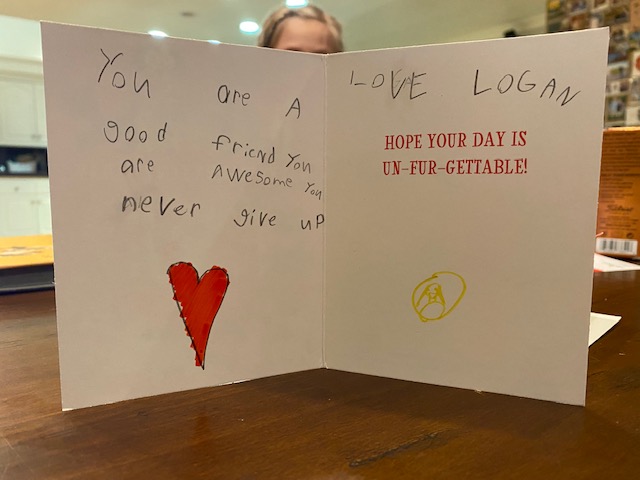

Jake: Well, I do want to talk about first the- my experience between the juxtaposition of those two things and how they often get conflated with one another. So my initial trip to a doctor when I first became ill, when I first started getting all these super bizarre symptoms that I’d never experienced before. The doctor’s initial question was, “Have you experienced a stressful life event recently?,” which I would later realize is effectively the doctor saying either A) he or she does not believe what you’re saying and just wants to send you off to a psych doctor to get evaluated so that they can, you know, prescribe or diagnose you with something that he thinks you might have. I spent 10 minutes in the room with this doctor, and he was ready to diagnose me with depression. I had experienced, and I’ve talked about this on my YouTube channel, many, many years ago, I experienced- it must have been over a decade of pretty severe depression and anxiety to the point where I had severe agoraphobia. Could not leave my room, could not leave my home, was too scared to go outside, it was really, really miserable. But because I had that lived experience, I understood intimately what depression and anxiety feel like and how they can affect the body even physically. You know, just because there’s a mental disorder, does not mean that they can’t affect the body in the physical way. So I understood like the idea of what he was saying, but I wanted him to understand this was something physical. Something was changing in my body that was making me really, really ill. And so yeah, I took his advice, and he gave me some medication for depression and sent me to see a psychiatrist. She, within a few weeks, determined that whatever was going on in my body was not due to mental distress, that effectively I had been dealing with the stress and I had had a stressful event in my life, but that’s basically what life is, is one major stressful event. But she said I was dealing with it in a healthy way. She said I was effectively practicing cognitive behavioral therapy. I didn’t realize that that’s what I was practicing, but I was practicing that, just trying to change the way that I was dealing with the experiences that I was having, even though they were stressful, I was dealing with them in a healthy way. So she said, whatever is going on in your body physically, this is not a result of mental illness. It seems to be something physical going on. At that point, I changed doctors. I didn’t want to see the initial doctor anymore. But since then, I’ve learned that they can exacerbate one another and that one doesn’t necessarily- one doesn’t necessarily mean the other, which was a change that I had to have in my own mind in that if I was experiencing anxiety, it didn’t mean that my physical symptoms were a result of my anxiety, and if I was experiencing- and some of the anxiety that I was experiencing were a result of my physical symptoms. So, for me, the major change in my life is that I don’t deal with chronic anxiety and chronic depression anymore. And even as a result of my chronic illness, even though it was depressing and very difficult to deal with, especially initially when I didn’t understand anything that was going on, all of the language was new to me, all the experiences were new to me. It was considerably more frightening than panic attacks and depression and everything else that I dealt with previously. Despite all that, I am very, very thankful that my mental distress has never reached a point of becoming unbearable. It’s always been bearable for me and I think one of the major reasons is because I’ve had such an incredible system of support, you know, both online with my audience of people who’ve been very supportive of me and, of course, the disabling chronically ill communities that I’ve been able to communicate, but my family and friends as well. Almost across the board, they were all supportive and helpful and loving and also respectful of whatever it was that I needed, understanding it may be distance. Like love at a distance sometimes for chronically ill people is a little bit hard for some people who haven’t experienced that, to understand that. You would think they don’t want to be isolated, and we don’t most of the time, but sometimes it’s a necessity. And I needed that from time to time and I’m really thankful for the people who respected whatever my needs were. It’s different from person to person and you really just have to have to speak to that person. Ask them specifically, “What is it that you need from us?,” because like I said, for me, I think that was the number one. Having a support system kept my mind in a place of as much peace as I could have expected, honestly. So, yeah.

Taylor: I’m so glad you were able to get that support. That is truly wonderful and I’m so, so, so happy for you in that aspect. And I’m really happy that you brought up loving people with chronic illness at a distance, especially right now in the time of this pandemic. There are so many people that don’t, that may not understand or have the knowledge that this is affecting people with chronic illness in such different ways and it doesn’t mean that we, you know, don’t want to spend time with people. We definitely do but we need to prioritize our health and wellness in this way. How would you say we as a people, (not just as the disabled community but all of us on this world), How would you say that we can support each other while also protecting and prioritizing our own wellness without any kind of emotional hindrance? So whether that is guilt or shame, what would be your recommendation for people who are trying to figure this out?

Jake: To like a non-disabled people or what do you mean specifically?

Taylor: Yeah! So it can be for non-disabled people for disabled for both, or any just, you know, blanket messages that you think apply to everyone. Just, you know, what would be your recommendation for people and learning how to prioritize their health without guilt or shame?

Jake: Sure, yeah. Well honestly, I feel like even in the question, you hit the nail on the head, at least that’s been my experience is that what kept me from a lot of the most positive experiences I’ve had from becoming ill, were guilt and shame. Accepting a disabled identity 100% rooted in guilt and shame, which brings on for me a healthy guilt, which is that from my perspective, that was ableism. That was me looking at the disabled community, people who are chronically ill, dealing, dealing with things that I didn’t understand, it was me like not wanting to look at it, not wanting to accept it, thinking, you know, whatever I had been fed over all these years systemically, that I don’t want to be that. I don’t want to be disabled. I don’t want to accept that. That’s weakness and I don’t want to accept that. You know, and it goes along to with what’s going on right now with COVID. There’s this- this is what like gets to me the most about it is people have this idea that I’m gonna quote, –not exactly–but this guy Hank Green, you may be familiar with him, John Green’s brother, they’re both authors now, but they had a YouTube channel, two brothers talking to each other. Hank Green said something recently, and like I said I’m gonna misquote him, but the essence of it was: “Dying from an illness or getting an illness, contracting an illness, is not a character defect. It’s not a failing of the person.” And so there’s this idea going around that–and even the way it’s been framed in the media–that it’s just the elderly, it’s just the sick and the weak–like the herd needs to be culled. And it’s just wild to me that anyone can think that way about other human beings. And to my everlasting shame, I just feel like–and I wouldn’t have gone as far as some people have gone in their thinking–but I know there are parts of me that believed some of the ideas that led people to think that way. Almost in this eugenics sense that it’s like–oh it’s weakness, oh it’s a failing of the person. It’s some moral character defect that they weren’t able to overcome. And even in a lot of the language, “they’re fighting cancer, he lost his battle to cancer.” No! That’s not what happened. The person died from cancer. They weren’t lazy, they didn’t give up. Those ideas just need to be abolished in my mind, 100% across the board. Especially if that is not in your lived experience, you have no room to speak on it. And I’m saying that from someone who lived on both sides of that line. If you haven’t experienced it, you cannot understand it. You can do your best to empathize, but you’ll never be able to understand it–and I hope and pray that that is your lived experience for the rest of your life, that you never have to experience any of the pain or chronic conditions that a lot of people suffer under. But it’s very likely that you will at some point. Most likely in your older age, you’ll experience it. So, if you get it now: what a blessing! If you get it now and you’re able to engage with people like this now, then when your time comes, you will have already been a part of the conversation, you will have already been a part of the community, you won’t be alone, you won’t be left outside. You’re gonna be a part of a community. It isn’t just for disabled people and chronically ill people to talk to each other. We really do need able-bodied people and healthy people to engage with us and be a part of the conversation, not just as allies, but as future members of the community. Because it will happen in some capacity, eventually.

Taylor: Absolutely! It’s really important to understand in all of these conversations that the disability community is vast, and it’s one that any one person can join at any time. Like, it happened for both of us; it was very sudden. And these are not singular experiences. So, as we are coming to the end of our time here, I just want to end on one final question that I like to give all of my guests to reframe us and help us switch our mindset from this conversation for the rest of our day, and that is just talking about one thing that we are grateful for in this moment. If you want time to think, I can go first.

Jake: Yeah.

Taylor: Yeah! For me, I am grateful that I was able to eat breakfast today. Sometimes that makes me a little bit sick, but today I was able to eat breakfast, and it felt great! And so I’m very very happy for that. What about you?

Jake: Well first of all, that’s great to hear. There was a time, I think it was about two years ago–my frame of reference for time is just non-existent; brain fog’s like a major for me–but I think it was about two years ago when I was experiencing what you were talking about, which is just not being able to eat and stuff, and I remember tweeting about it and talking to some other people who were experiencing it. And the joy that people would experience, when you have something taken away, and when you’re able to get it back even in just a modicum of how much joy it brings you, it was really really refreshing to read that from a lot of people who had been experiencing the same thing and seeing some relief, so I’m really glad to hear that. For me, I have so much to be thankful for. It’s really difficult to even pick something, because I’m coming from a tremendous place of privilege. I worked with my friend Owen Rogers for many years–some people may be familiar with him–we did a bunch of videos on YouTube, a bunch of goofy weird stuff together that was just fun, shouted a bunch of nonsense in the woods for hours and hours. He provided me with a job. I mean, I know that I earned it from working really hard together with him, but I just want to publicly thank him again for providing me a job when I became ill, knowing that I was not in a stable physical position, and still allowed me to score music for his first TV show that he got greenlit. That was a really big deal for me then, and now, looking back on it from a perspective where I can understand how much of a privilege it is to have worked remotely as a disabled composer–I don’t know another disabled composer who had that opportunity. I’ve been looking and asking and trying to find someone, trying to build a core community of people who have had that same experience, and I’m really struggling to find somebody. And now, looking at COVID and the way that is, like, I’m just so thankful to him, and to TBS, and Shadow Machine for allowing me to do that, and when I became too ill to do that, they allowed me to be a music consultant on Season 2, and when I couldn’t do that anymore, then they were like, “hey, do you think you could do some punch up writing for Season 3?” The fact that I have been able to work through this pandemic, again, I just have so much to be thankful for. And I’m struggling with the shame and guilt of the fact that I even have those opportunities, but I’m trying to just accept that I’m thankful for them. So, I’m just gonna stick with that, that like, I know that I have a lot of opportunities that many other people don’t have right now, and I’m really really thankful for that and for everybody who’s supported me through it and helped me get there. It’s a dream come true.

Taylor: That story brings me so much joy, to hear that your community has supported you so strongly through all of this, so thank you so much for sharing that. And thank you all for listening to this episode of Channel Kindness Radio! For more content like this, you can find it on ChannelKindnessRadio.org.

Voiceover: You’re listening to Channel Kindness Radio.