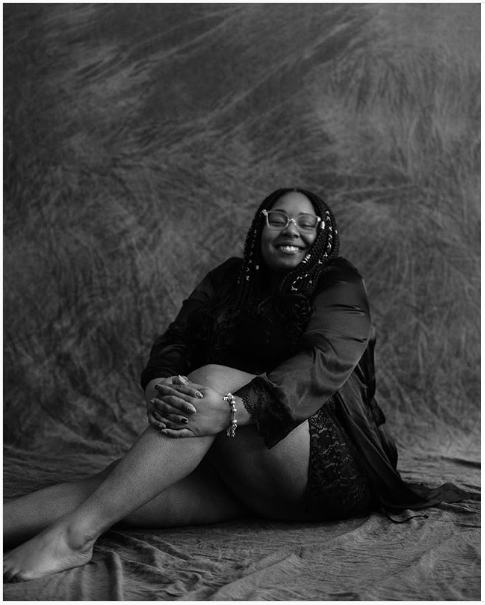

Nethra is an anthropologist, coach, writer, and co-creator of The Lab for Listening. She has a PhD in anthropology from Stanford University and her work is grounded in a unique method that combines Nonviolent Communication (NVC), ethnography, and design thinking.

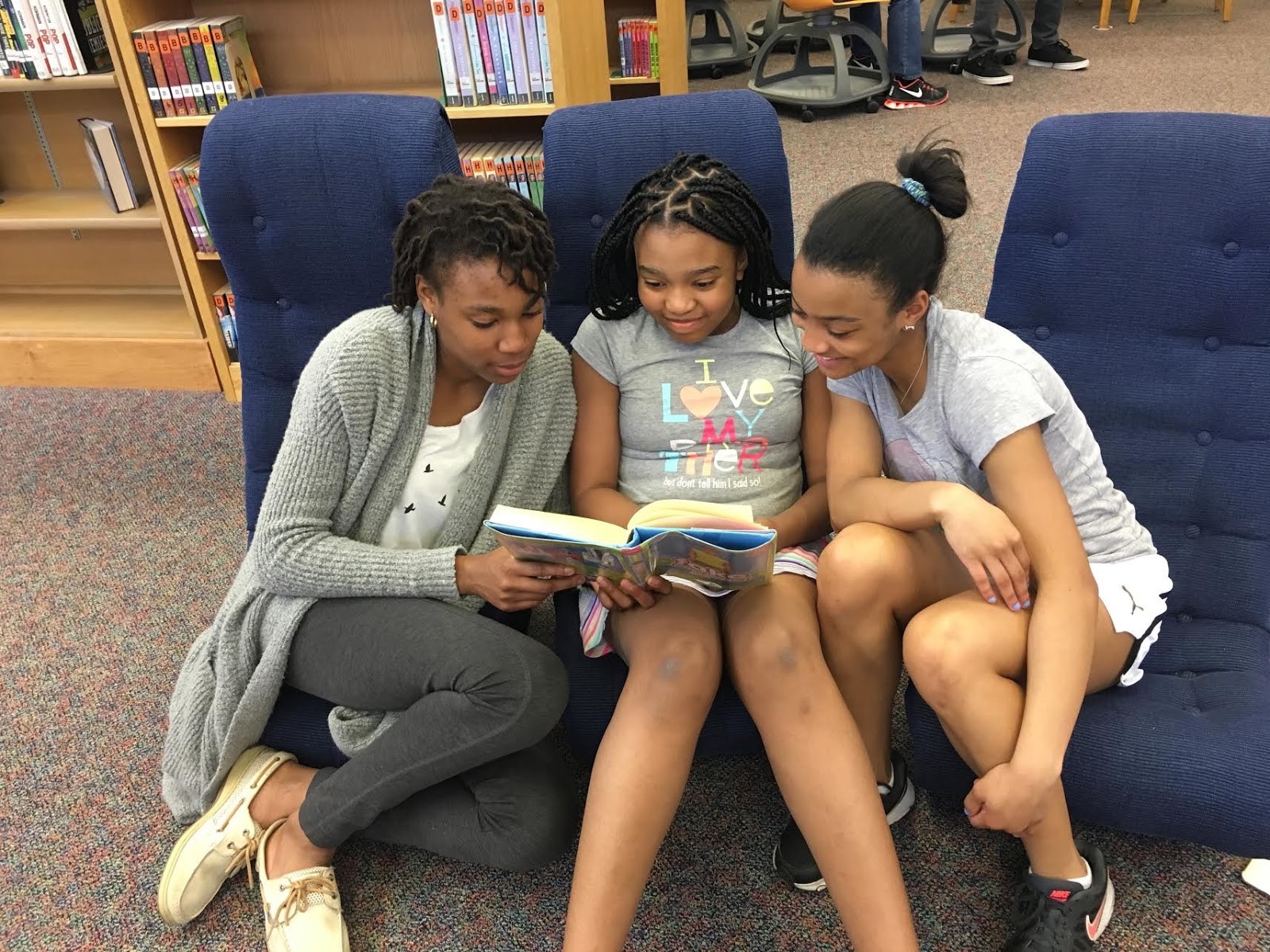

This is a story. When I first met Nethra virtually in early 2021 in what I had considered a “networking opportunity,” I felt a profound sense of calm and warmth wash over me. Despite the digital divide and the challenges/absurdity of building a friendship and connection in the pandemic, Nethra was a fresh departure from the high pressure networking environments I had grown accustomed to. A few minutes into our first conversation, I realized that Nethra saw me as fully human, beyond my professional role and our shared interests as anthropologists. Nethra’s amazing ability to listen for the silences and humanize people inspired and moved me.

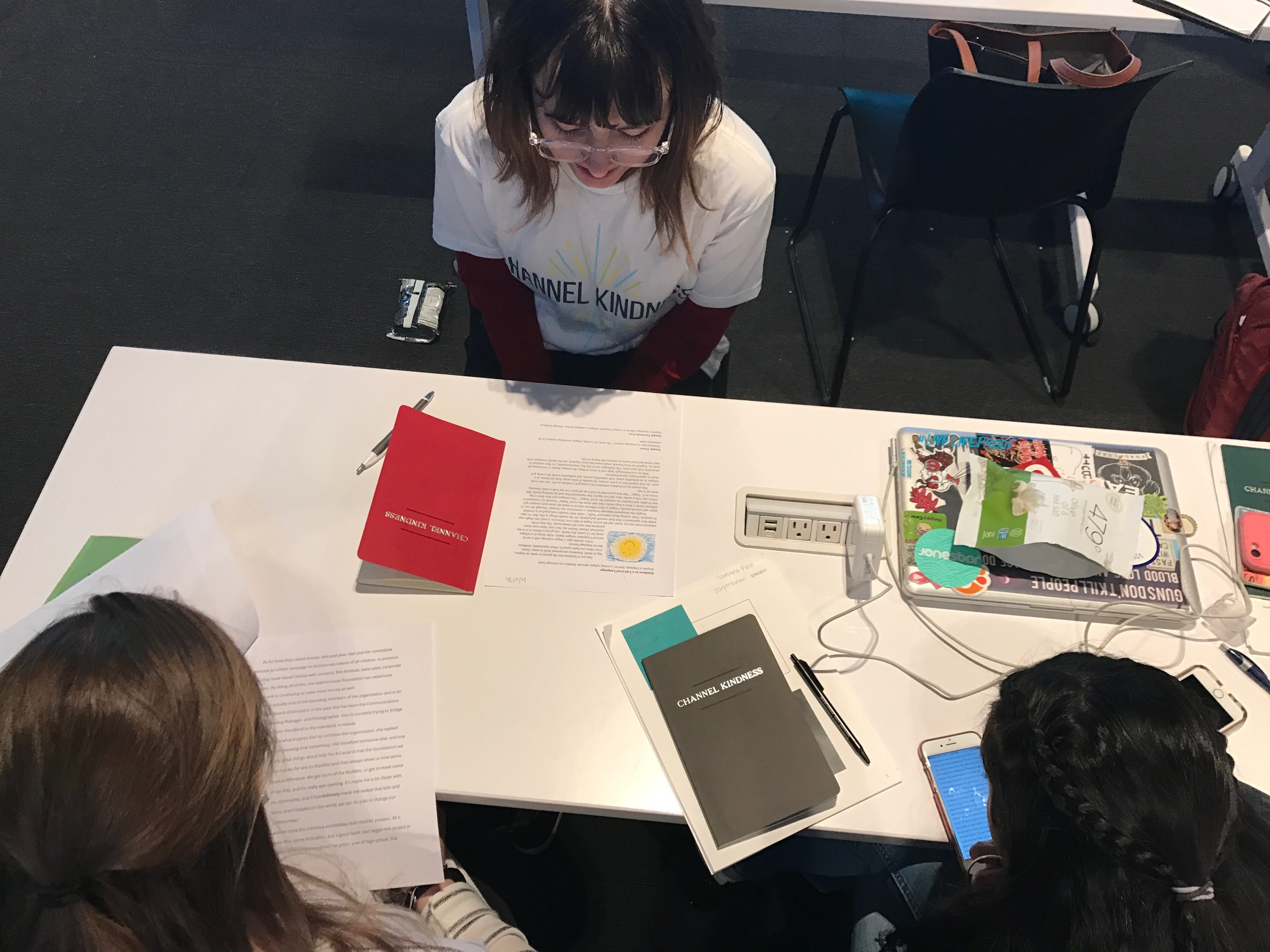

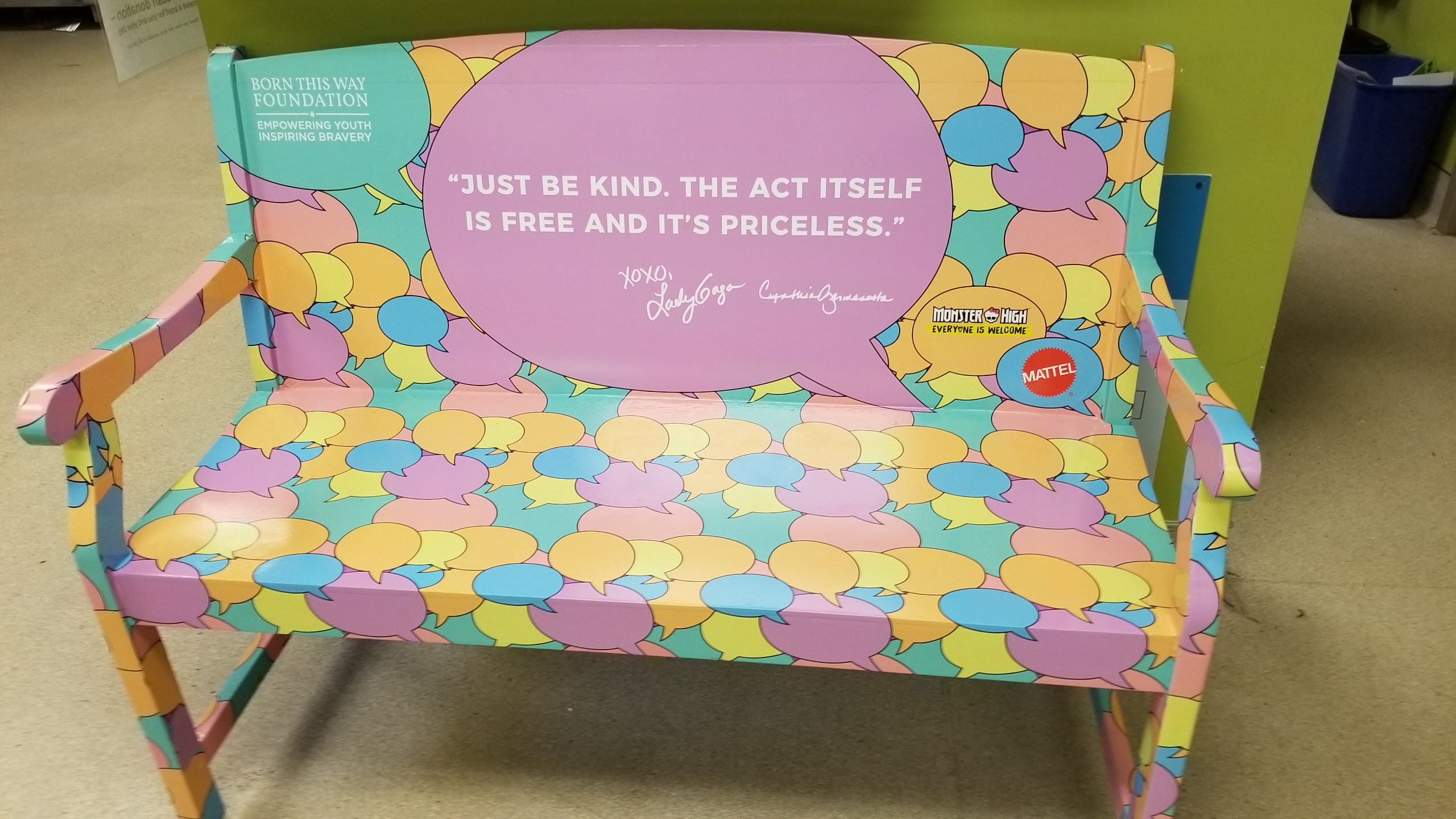

A few months later, when Nethra and I reconnected to chat about her journey and the story of co-creating her new venture, The Lab for Listening, I was once again reminded of the incredible ways through which Nethra continues to practice and extend kindness and empathy in the world.

Nethra’s story and thoughts taught me what it means to be human: to listen with curiosity and empathy, connect with each other in alienating landscapes, and advocate for our needs. Read my interview with Nethra Samarawickrema:

Varshini: I am so excited to chat with you! To get us started, how would you introduce yourself in your own words as you’d like to be recognized today?

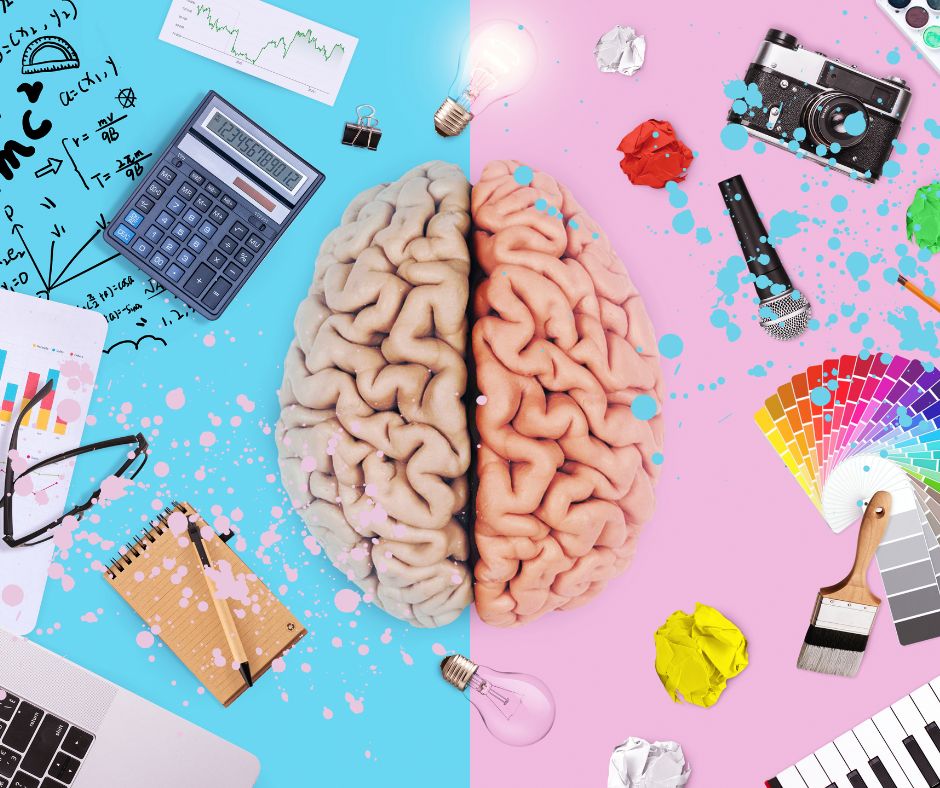

Nethra: I think I’m someone who has always been interested in listening for what’s underneath the surface of things. That is the foundation of everything I’ve done so far. Initially, that’s what drew me to anthropology because I wanted to really understand what the world looked like from different points of view, and I always felt like listening could be a way of seeing the world with new eyes. From anthropology, I learned to decenter the way I see the world and actually meet someone with curiosity. This has transitioned into my individual and group work with people. I have started to see the power of curiosity and empathy. The other part of my life that has been really important is creativity.

Varshini: Tell me about The Lab for Listening. How did you bring so many different approaches– ethnography, human-centered design, empathy, Nonviolent Communication (NVC) into this?

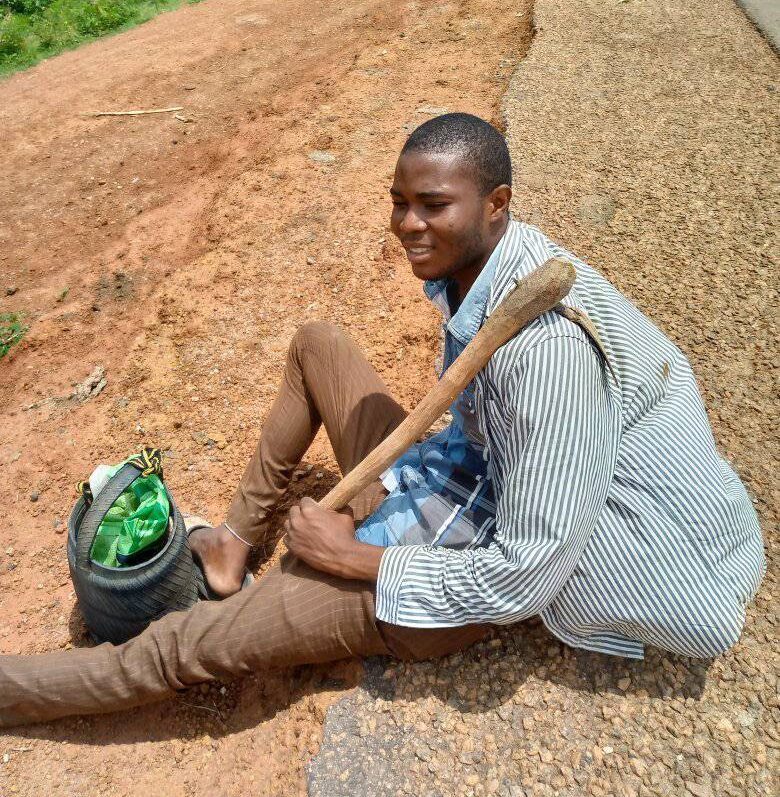

Nethra: The part about ethnography I love the most is doing fieldwork. With fieldwork, I had to listen with all my senses and not only did I have to listen with all my senses, I had to ask how and where do people feel heard. So my research is on mine workers and traders who were in the sapphire trade. If I spoke to the laborers at work, they wouldn’t tell me what their labor conditions are like so it was not just about listening, it was also about asking (myself) “what do I need to do to create the conditions in which they feel comfortable to speak?”

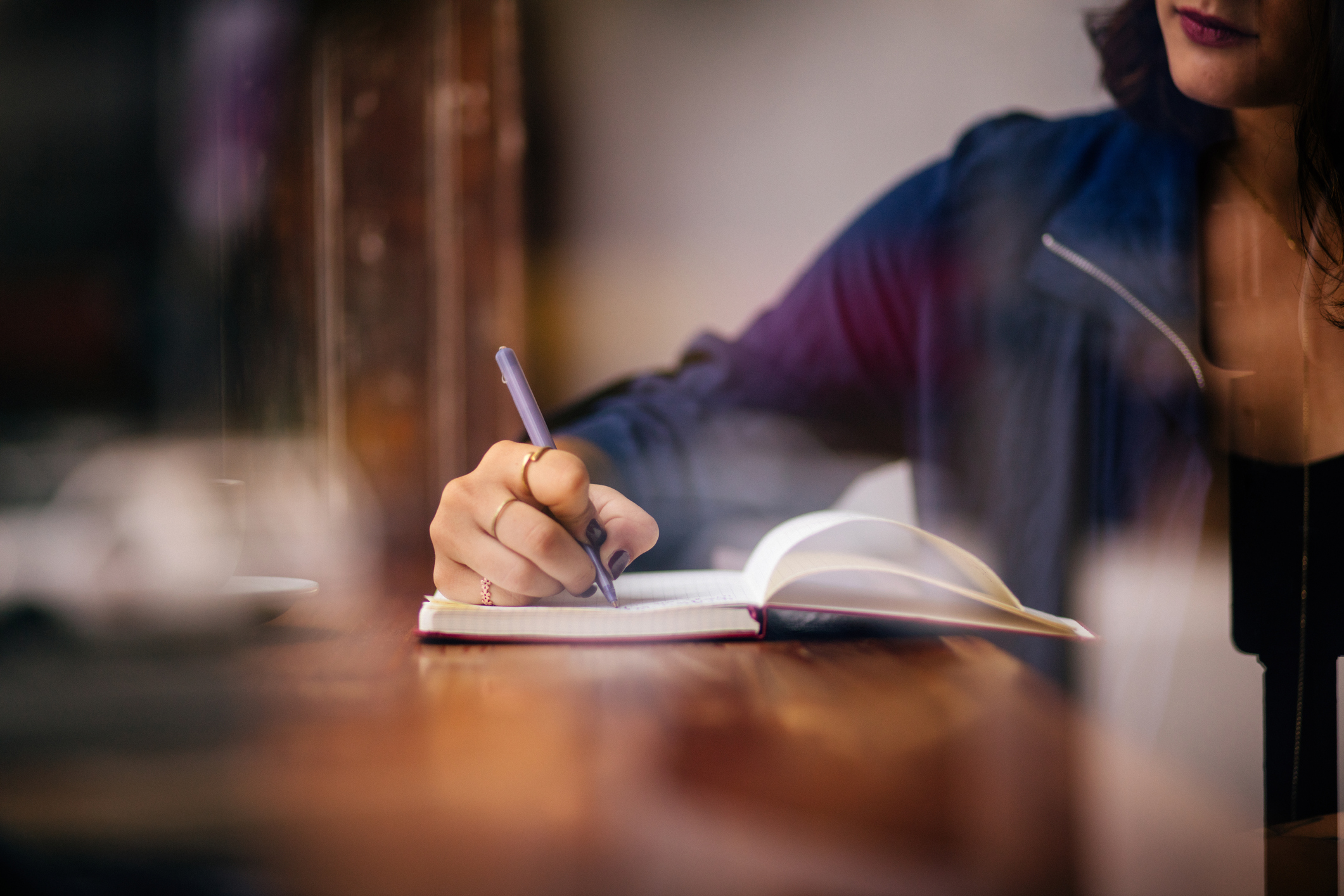

When I came back to the academy from the field, there was such a pressure to “know,” and the discovery part of it felt a bit lost to me because of the pressure to make an intervention that was going to change the field. The writing part of it (PhD program) really shocked me because I found myself stuck, just totally unable to write, spending days in front of the computer — out of fear, not being able to say the things that would get the grants, or the job. I felt stuck. It was the biggest gift of writer’s block I have ever received. It was in getting myself unstuck that I started to find my way here.

I think the fear was that I had to have everything figured out before I wrote. I was afraid of getting things wrong — not being theoretical enough, not having the right intervention, or not having enough citations. The shift happened when I discovered design thinking, and I started reading about writing. I realized that the creative process is a process and that you can actually imagine and not know and discover. That was what drew me to design thinking.

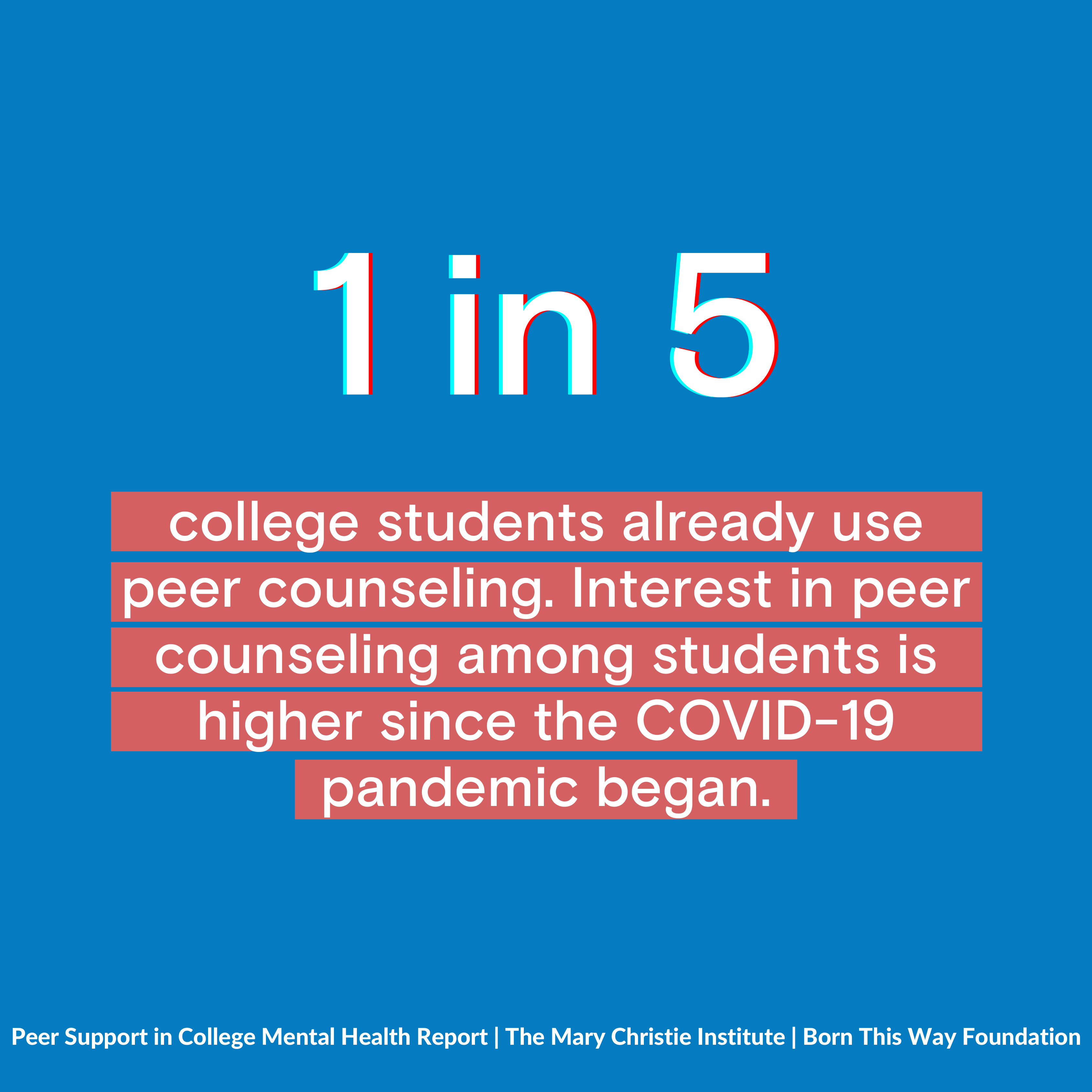

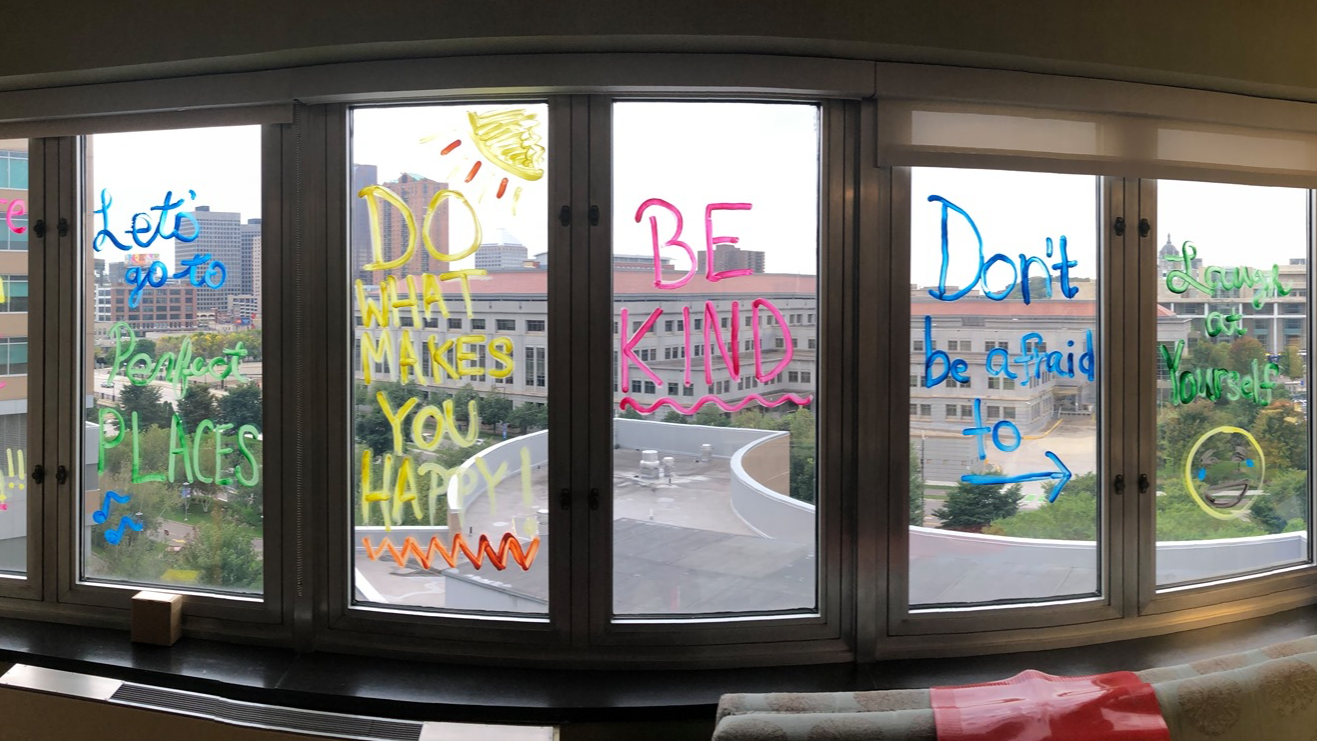

While I was doing this, I was also getting trained in Nonviolent Communication (NVC). I have been practicing it since I was a teenager but I found myself really stressed out in graduate school. Like almost every other PhD student I know, I just had a ton of anxiety, and as a way to self-soothe, I started to go to these classes. One of the things that happened for me that I noticed is that when I would show up at these places, I would be heard. I didn’t have to perform. The people who were practicing these listening skills would listen to me, they would be listening for what mattered to me, and I didn’t have to be anyone or become anyone or have accolades in order for someone to know what’s going on with me. I would just relax, and I would feel safe. It was after these workshops that my best ideas would come.

I started to notice something really odd, that I had so much mental clarity after I was in a space where empathy was abundant. Ironically, when I was going back to academic spaces and conferences, I noticed that everyone was talking but very few people were actually listening. I had a sense of being distressed and it was very odd because the more professional skills I gained, the less confidence I had because the pressure to perform was so high.

Varshini: That’s beautiful. Thank you for sharing that. I especially loved the part about feeling more and more disconnected as you continued to gain professional experience. It’s counter-intuitive but speaks to how a space with abundant empathy is what you need to do your best work.

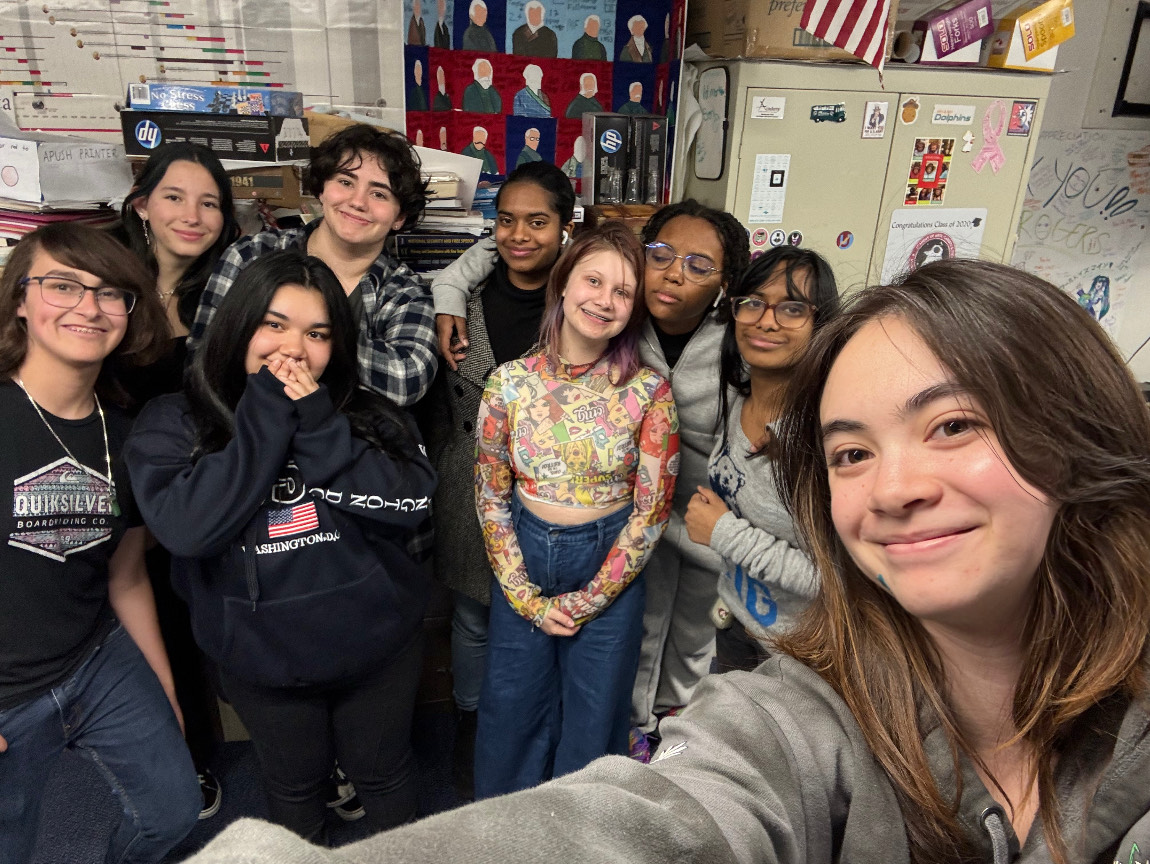

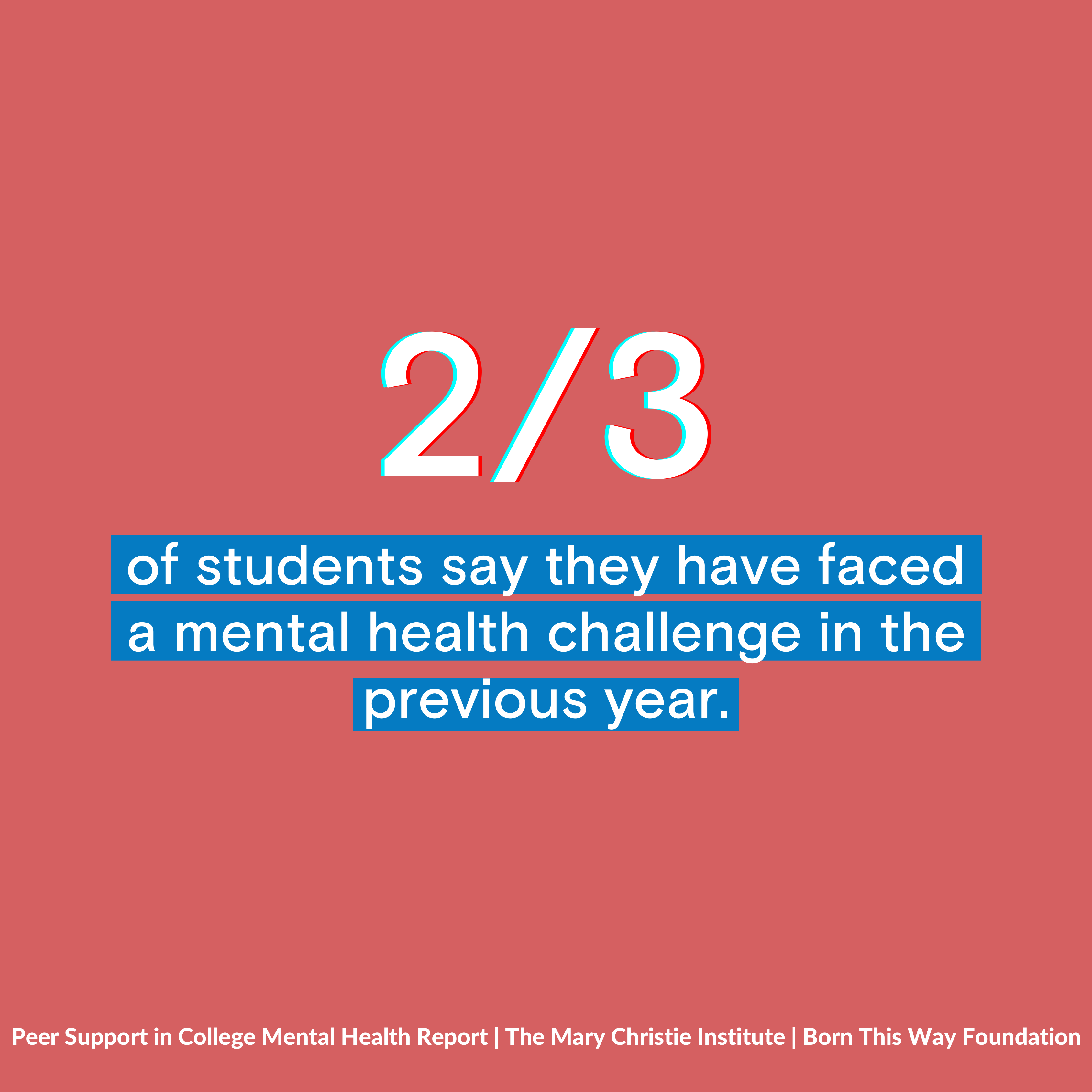

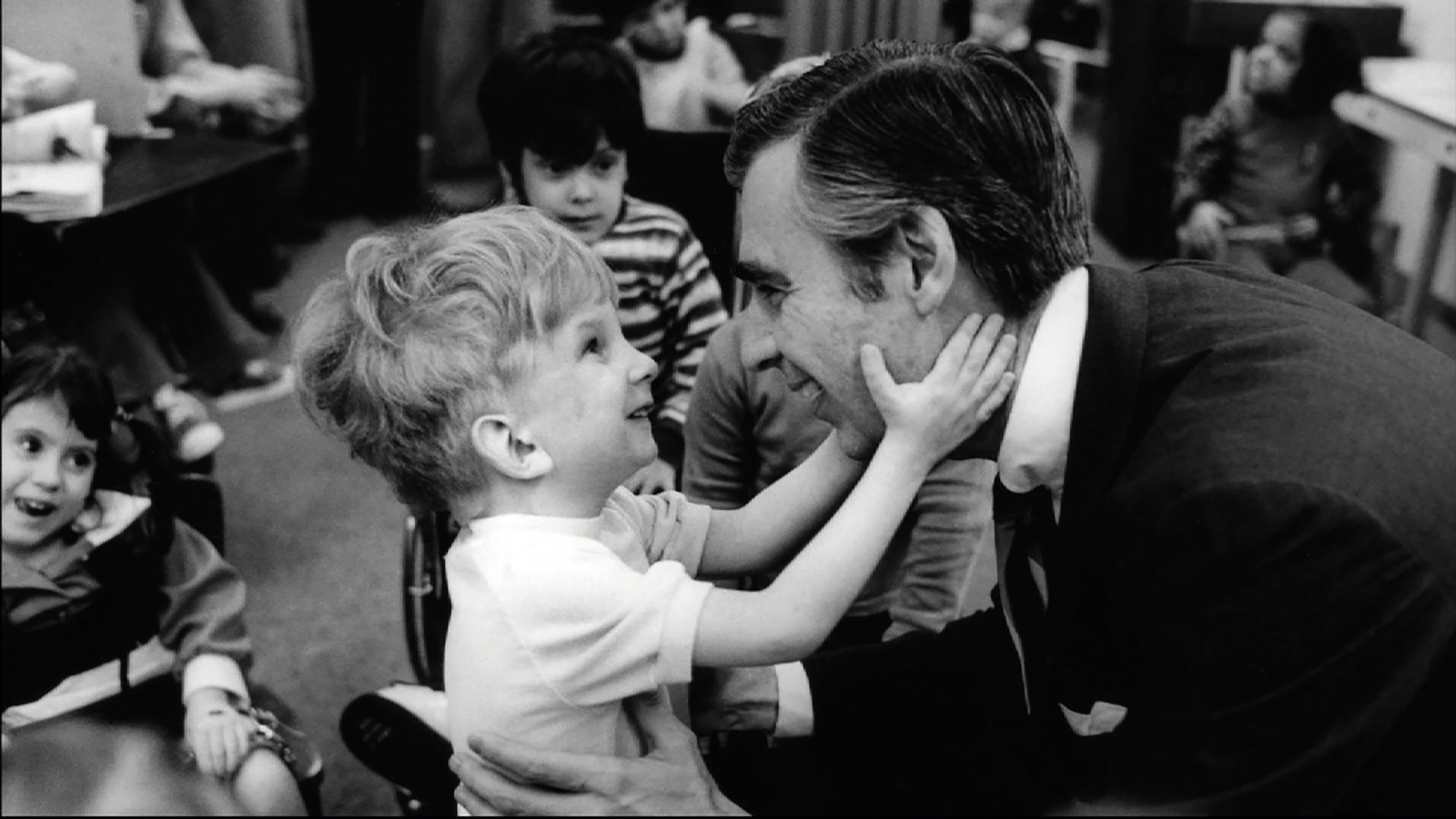

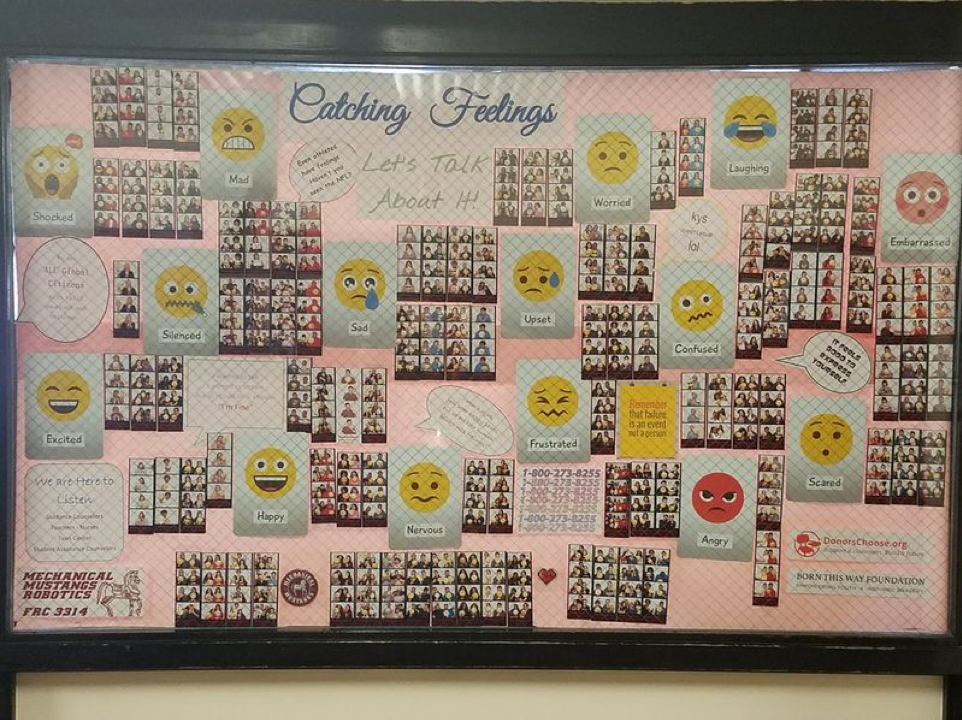

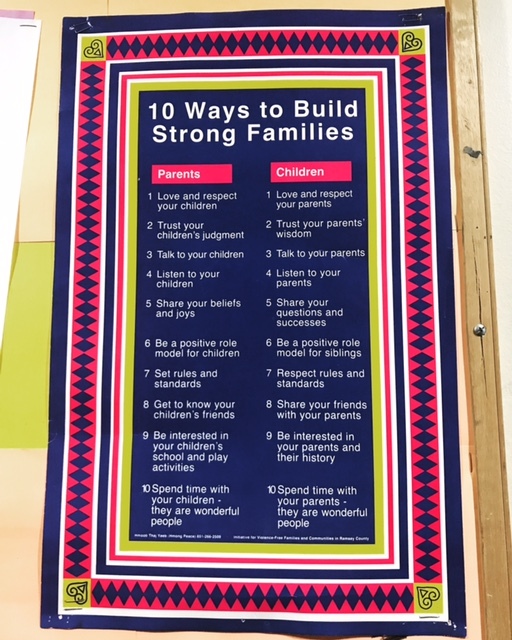

Thinking about this from a broader and youth-based perspective, I was wondering if you could talk to me about the role and capacity of empathy in people’s lives. What kinds of changes have you noticed in people when they practice and receive empathy?

Nethra: I think that empathy helps people become unalienated from their needs and the things that make them feel alive. There are so many definitions of empathy. For me, what really feels true is what Carl Rogers says when there is deep empathy, the person has both a sense of safety and a sense of freedom to express whatever is happening for them. Or as Winnicott says, you hold space and provide an unobtrusive presence in which people can explore themselves and discover new things. That’s where I think empathy and creativity come together. I really do think that when judgment is suspended and people have the space to explore and experiment, new ideas can come up when people are not triggered, when there is no punishment or harsh criticism, then our minds can go to places where they may not have gone before.

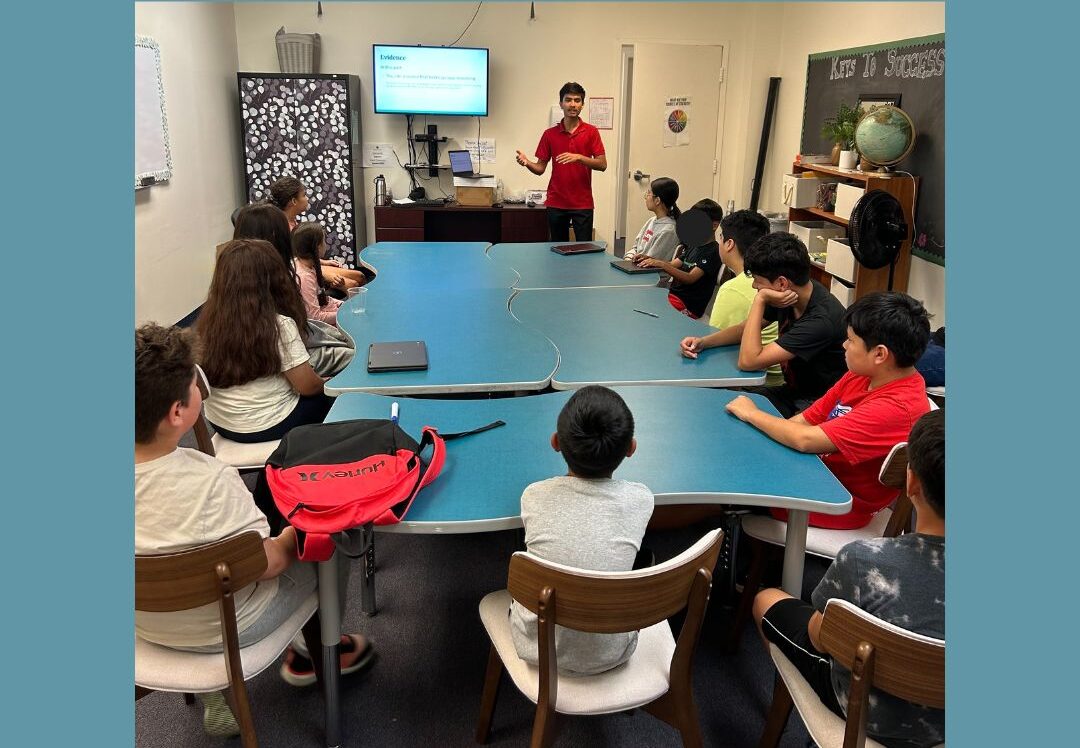

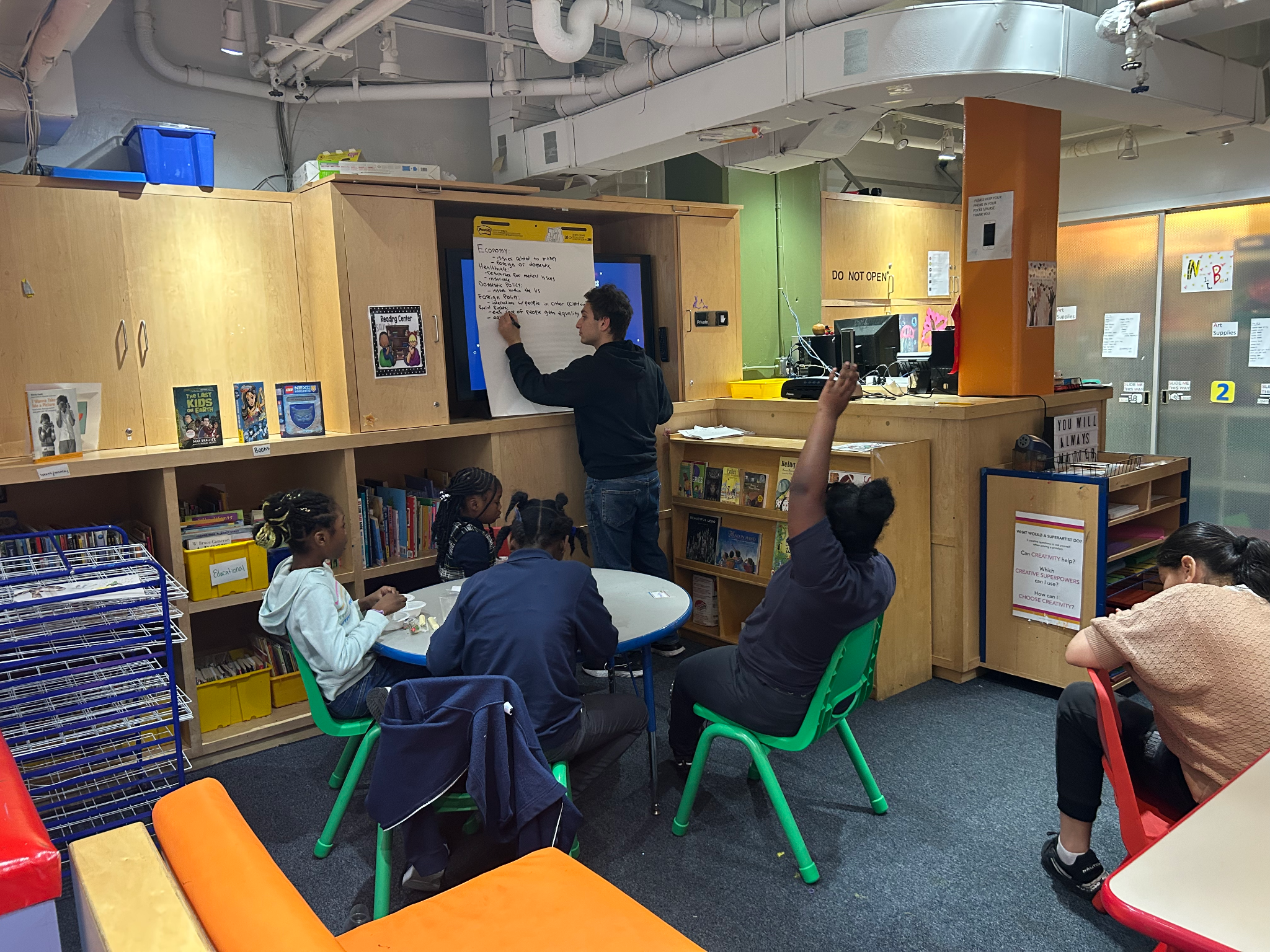

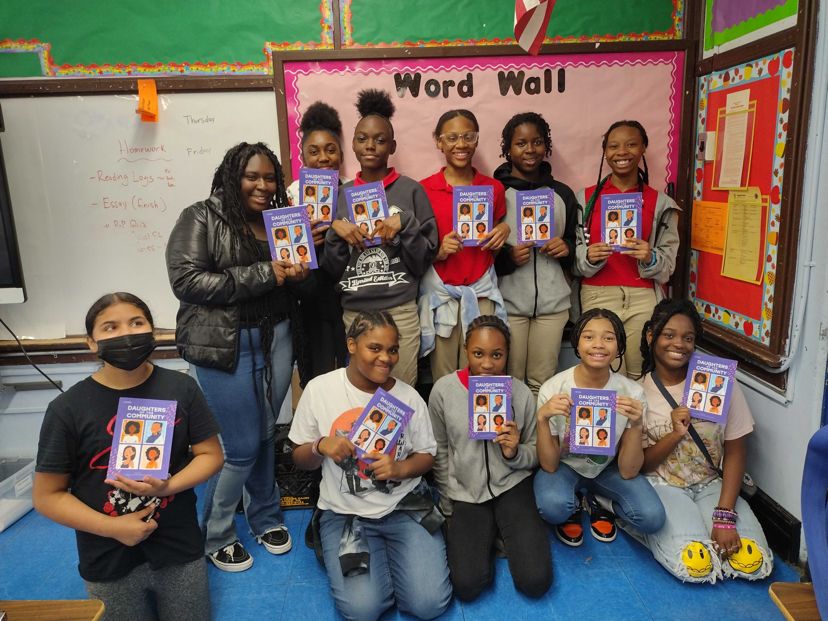

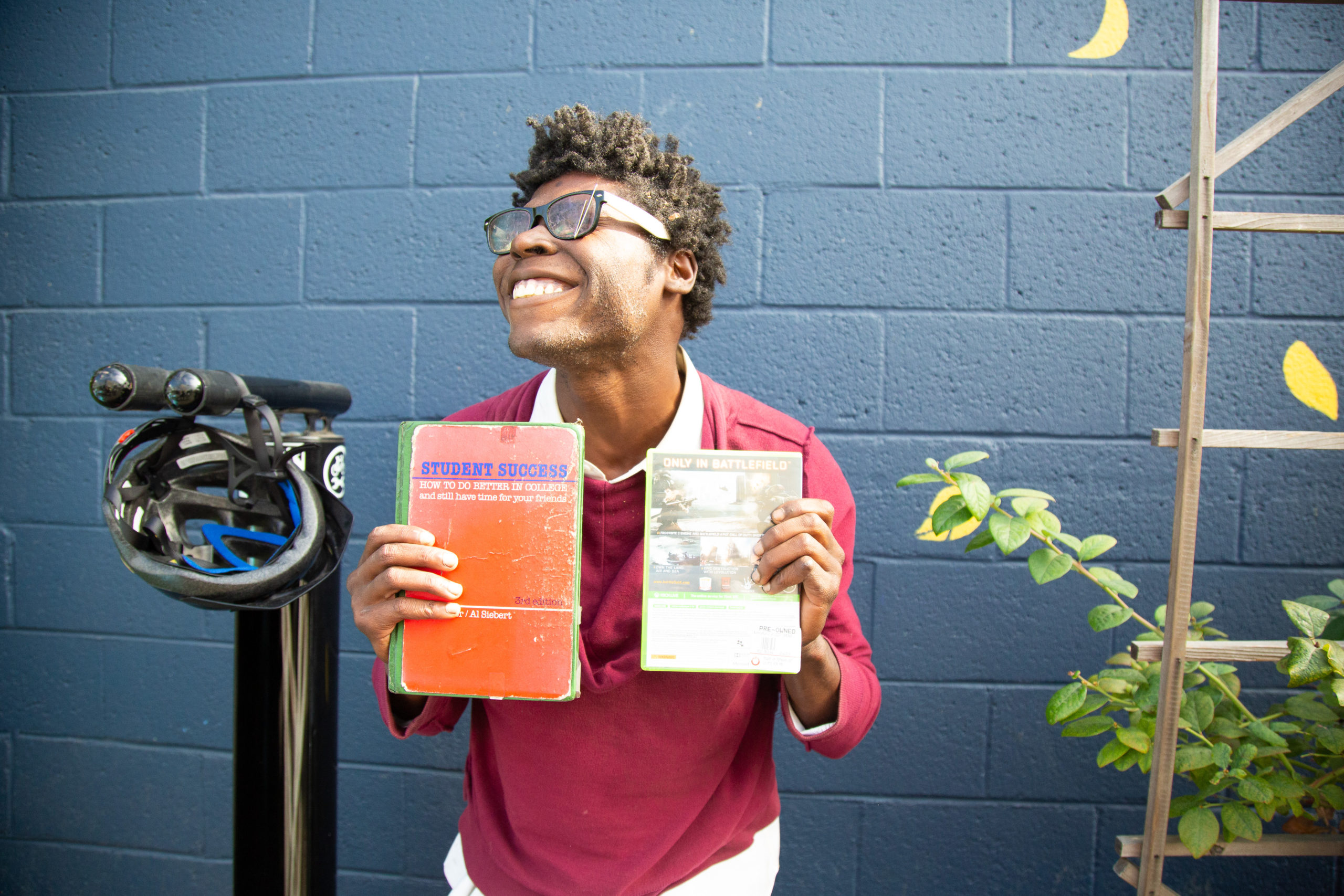

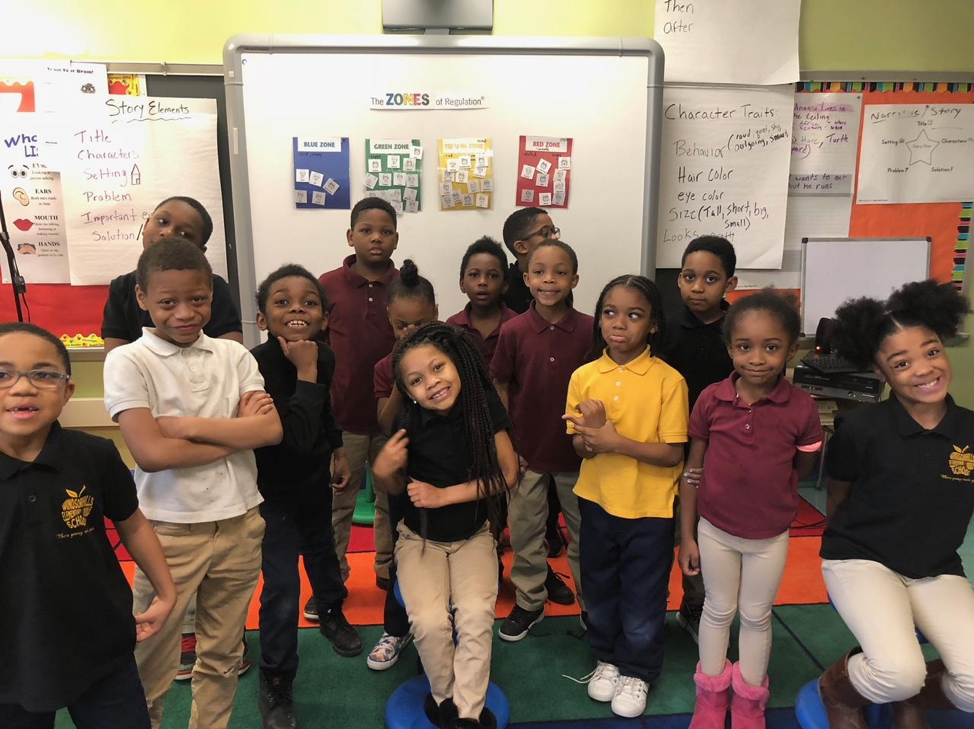

In education, I don’t think the role of a teacher is to teach or impart knowledge but to create a space where discovery can happen. Especially for young people, the most important thing for us to protect is each and every person’s curiosity and their sense of agency to explore their curiosity and their sense of permission to explore the things that bring them alive, which I think gets systematically curtailed as you enter institutions.

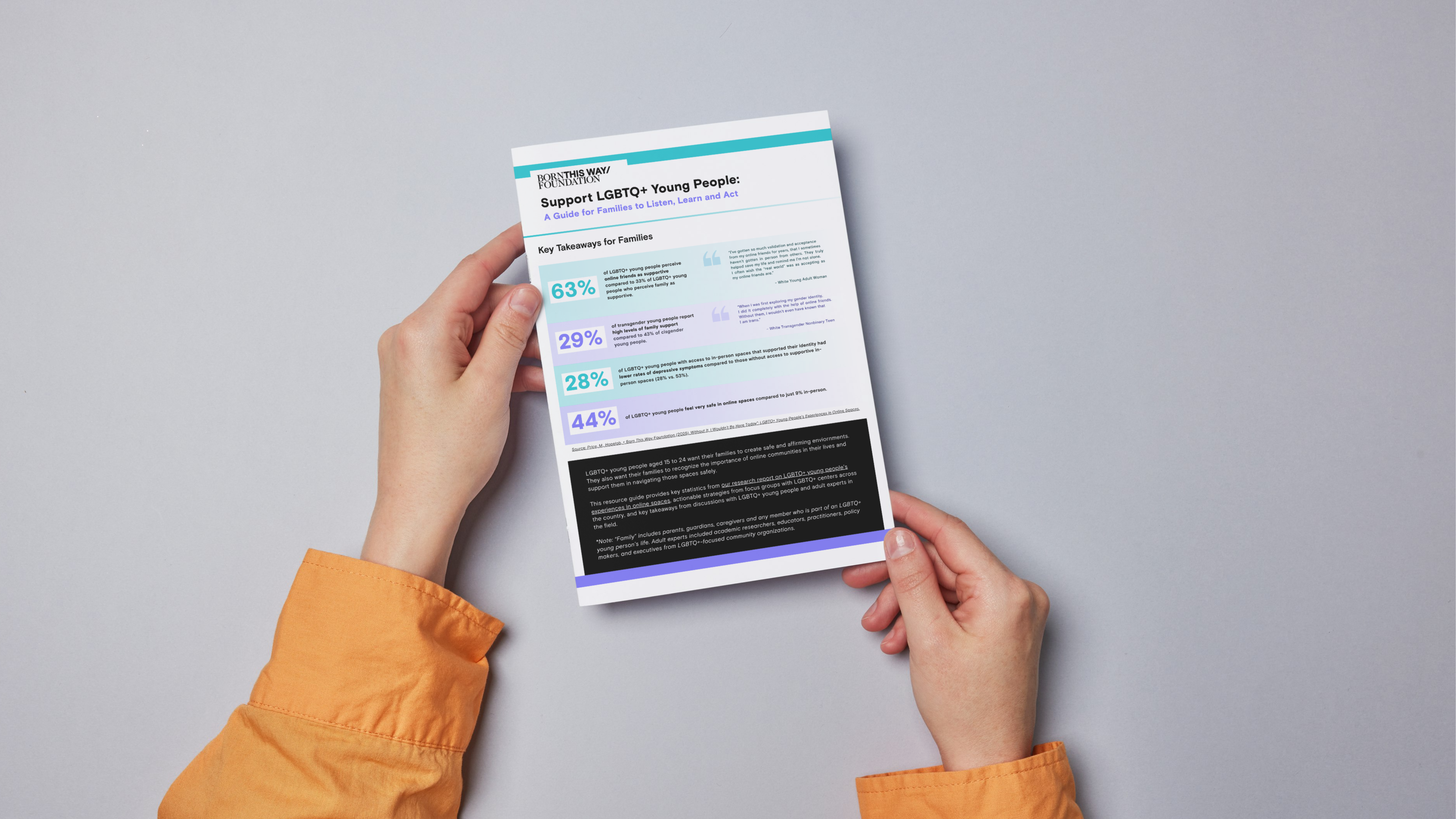

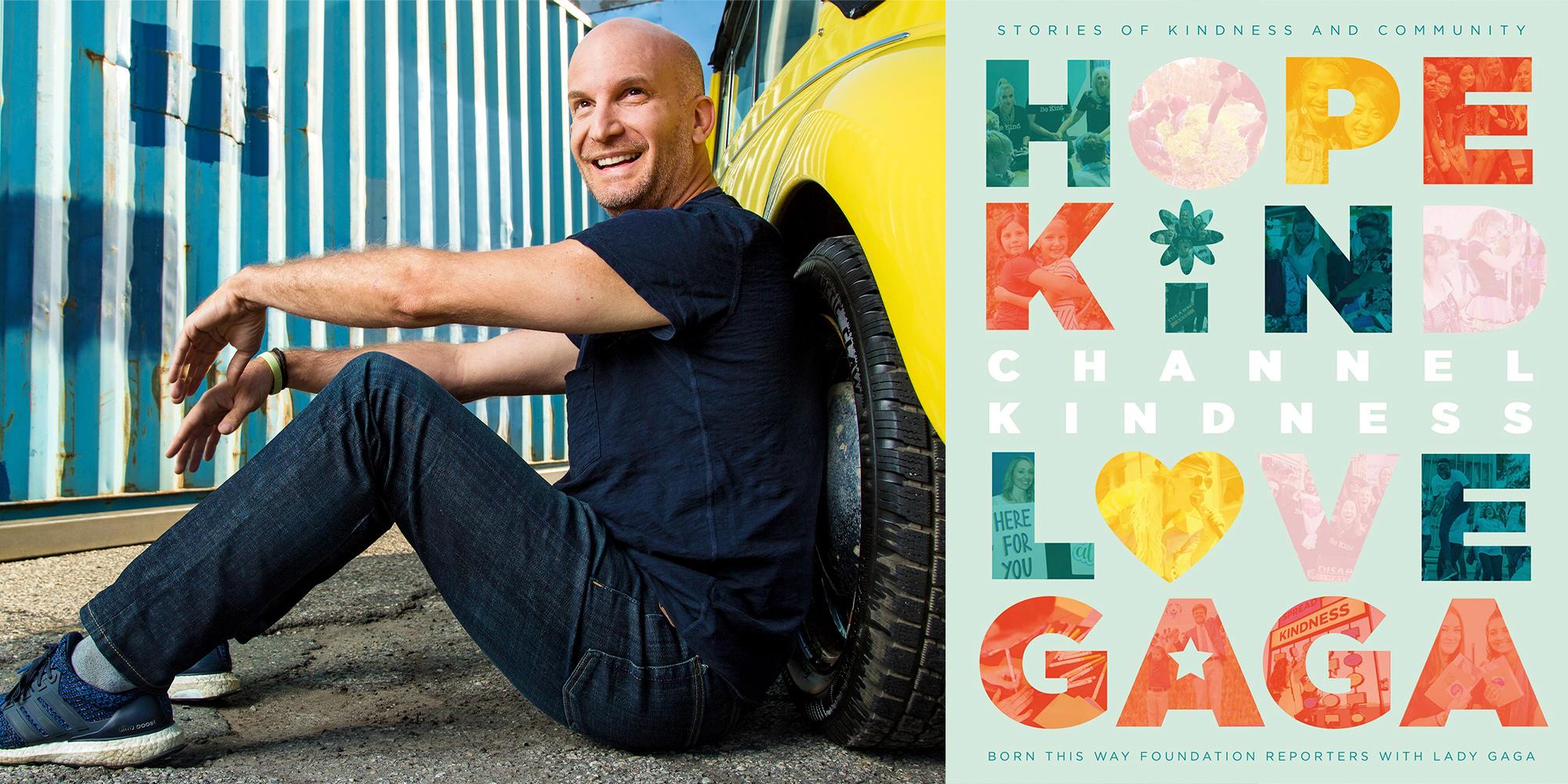

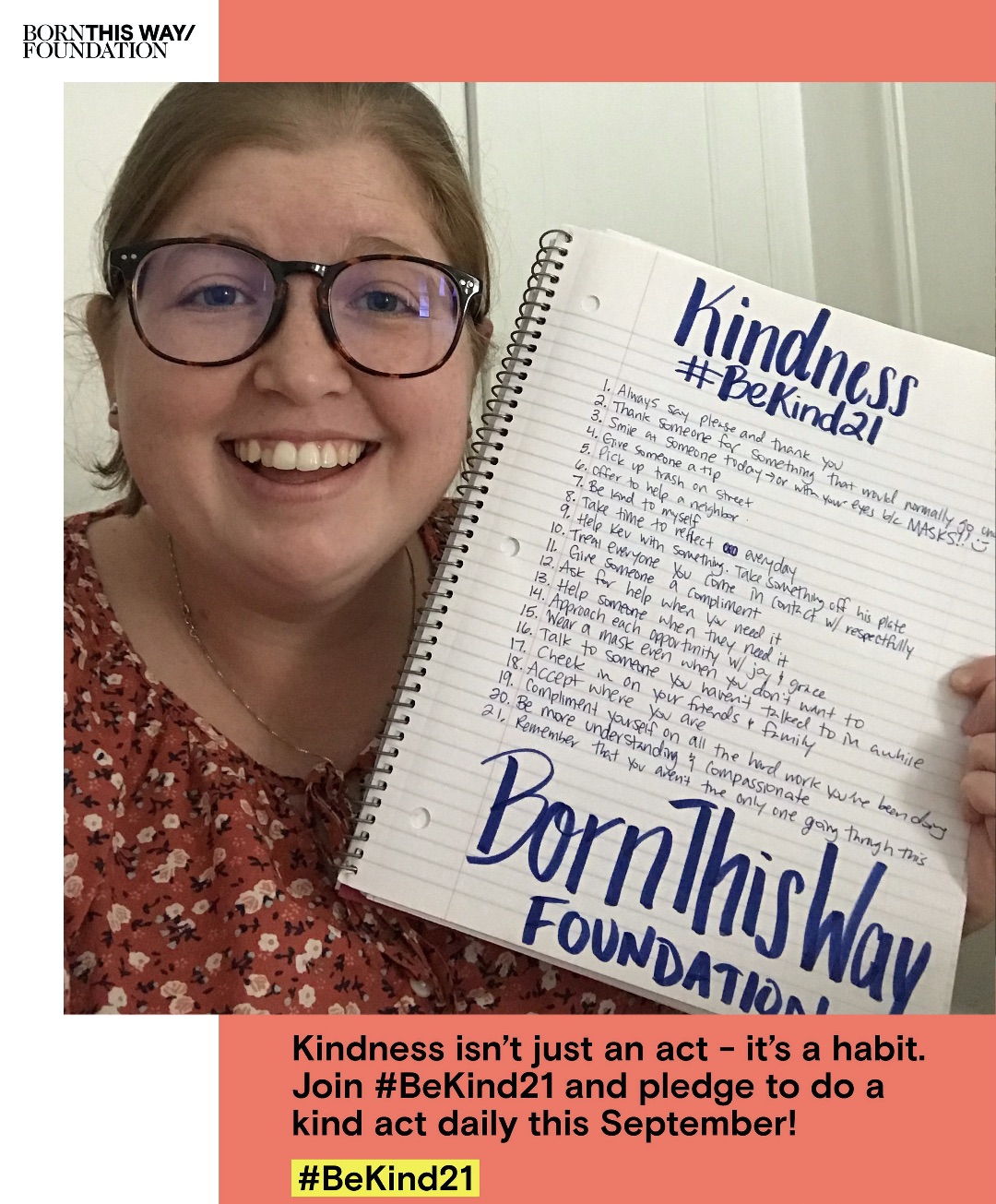

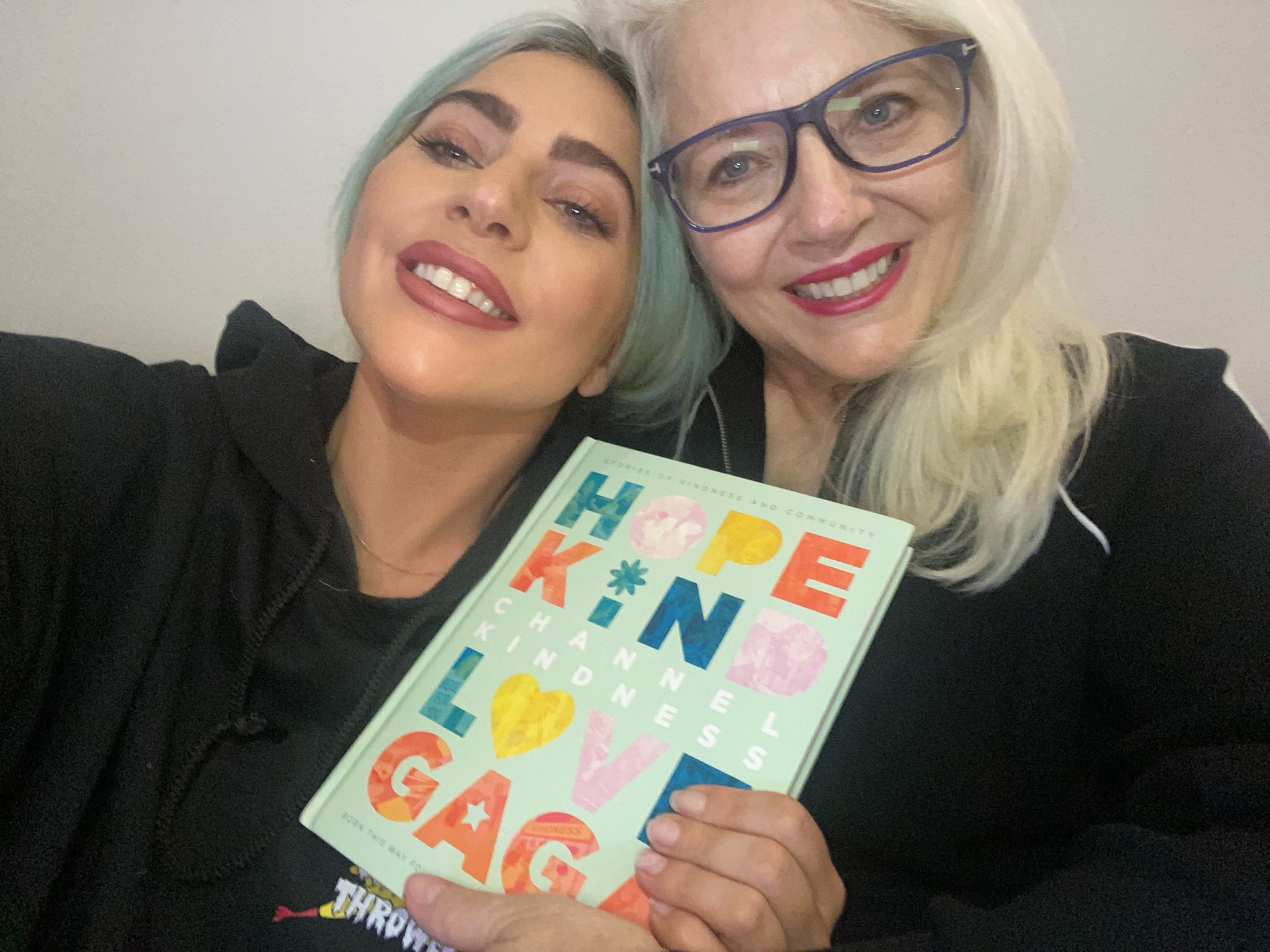

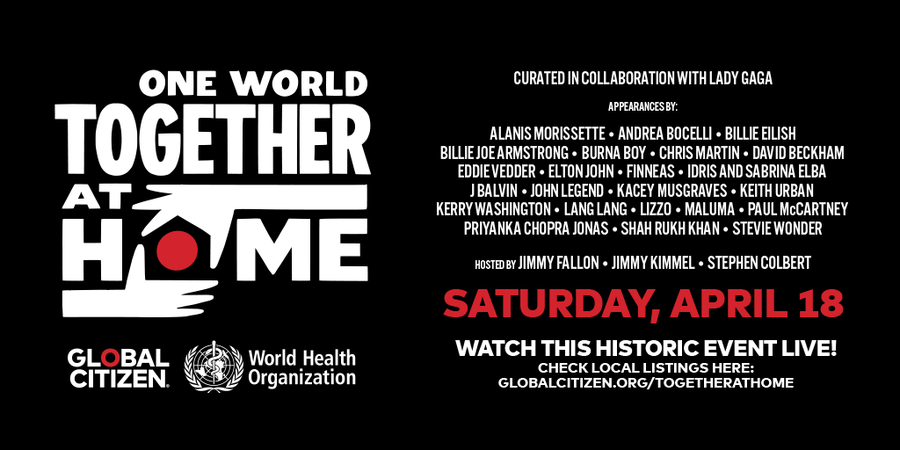

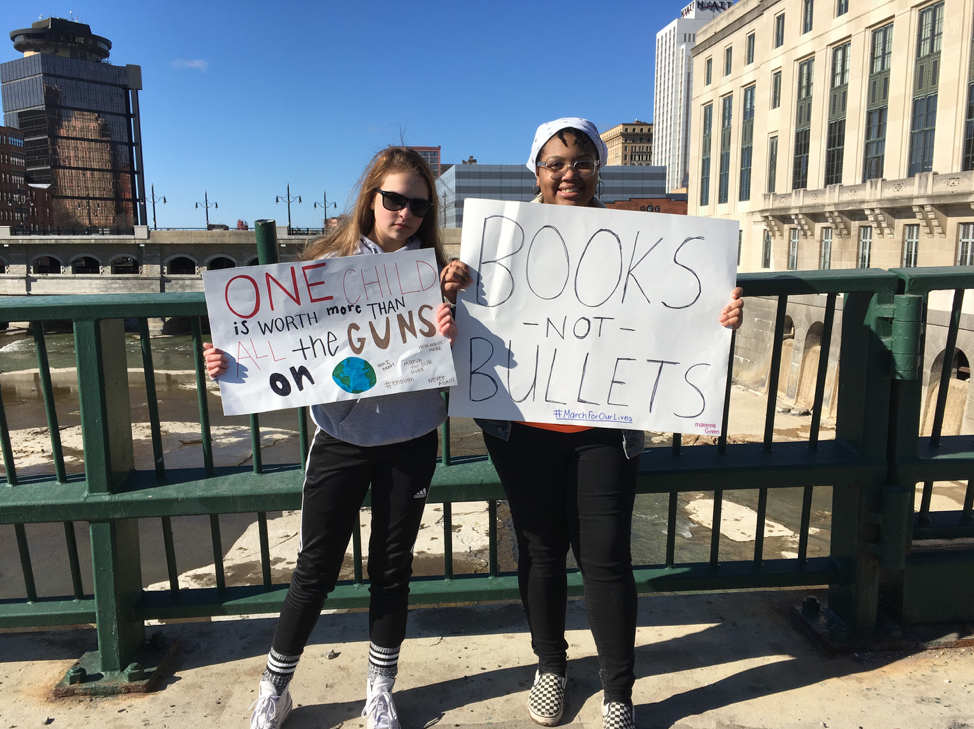

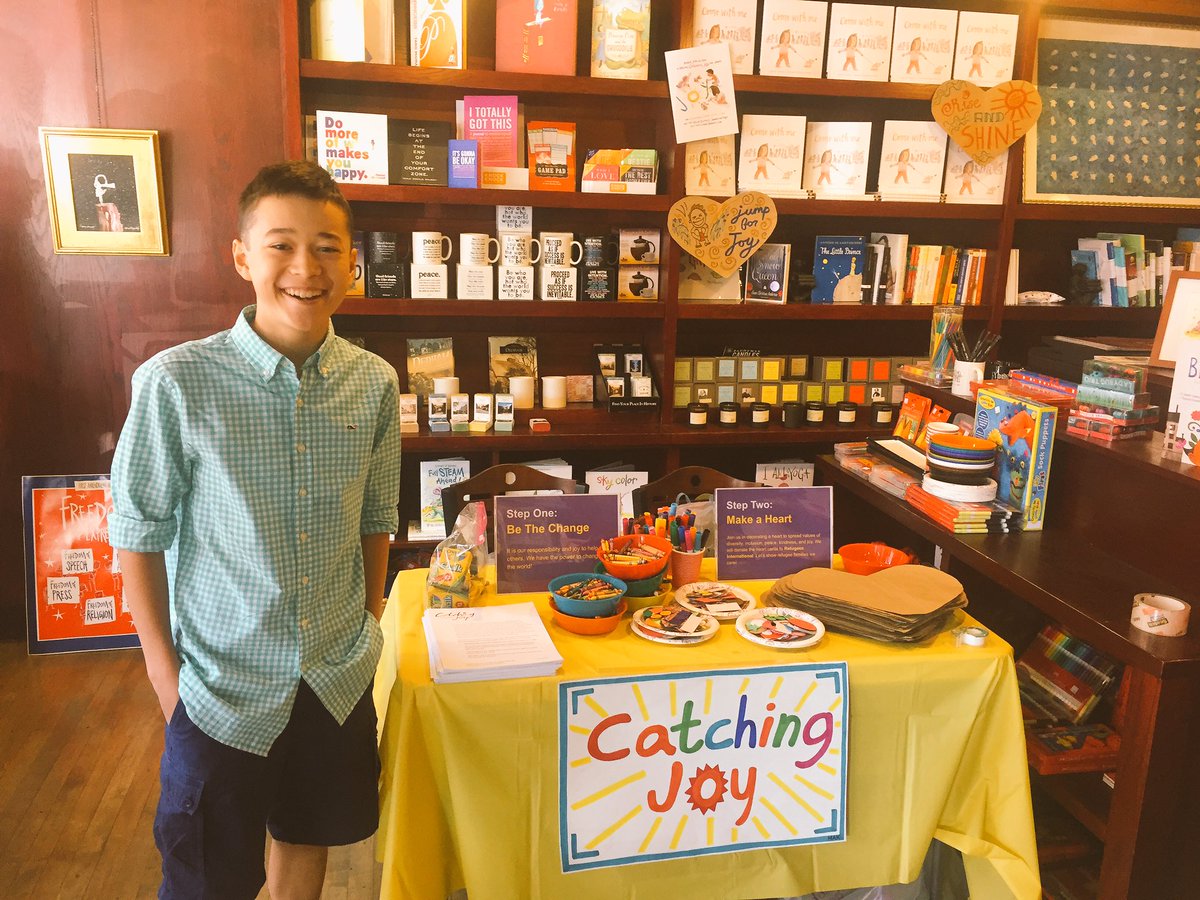

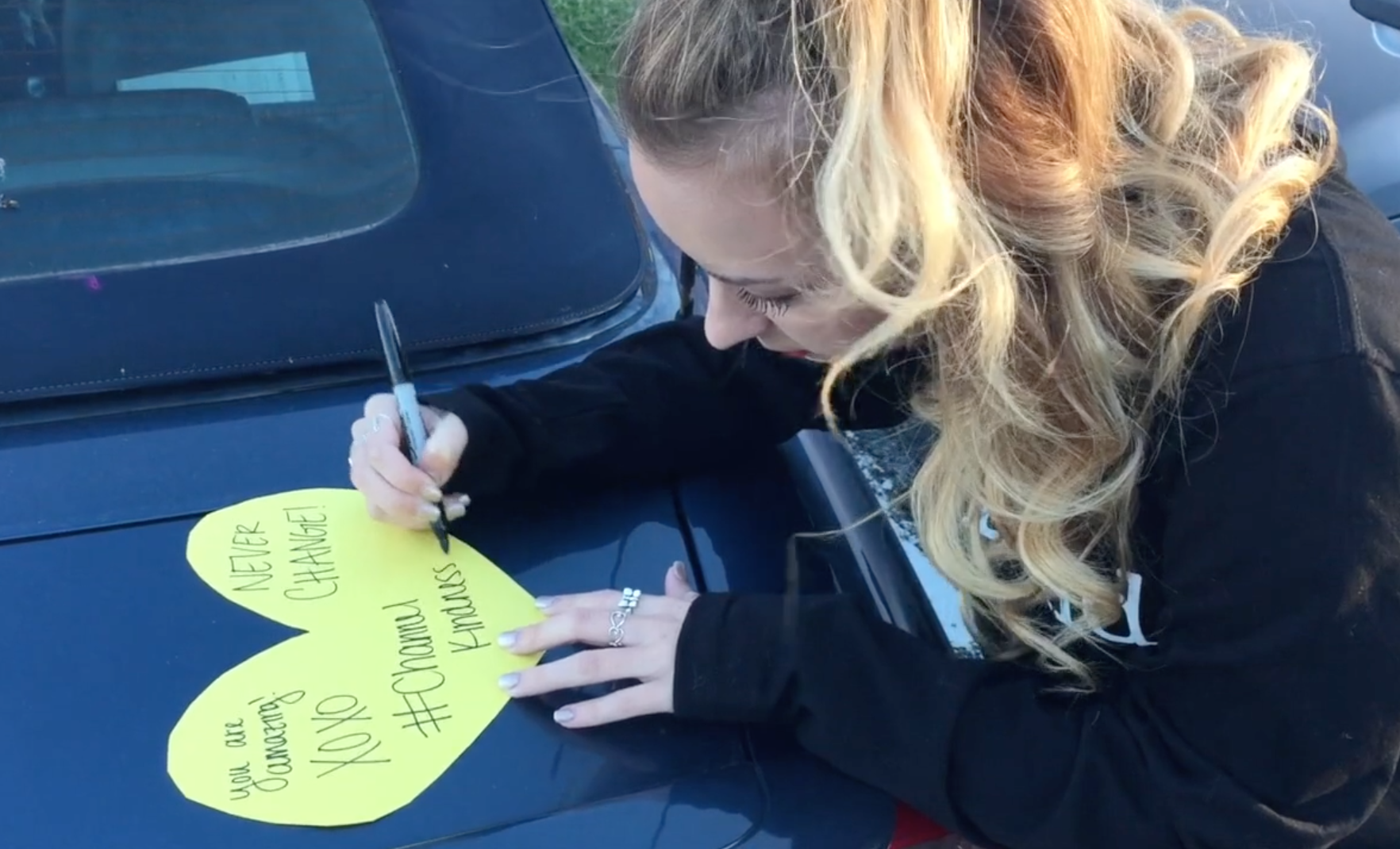

Varshini: Yes, and having that courage to explore things that are alternative and divergent! We at Born This Way Foundation are all about inspiring kindness and bravery. Could you talk to me about what kindness and bravery mean to you? Could you also share an anecdote of when someone’s kindness impacted you?

Nethra: I think in terms of bravery, this past year has been a lesson for me in following what matters to me in the space of the unknown. Just because how you are going to make something happen is not clear, it doesn’t mean that it’s not possible. I learned this most powerfully in co-creating the Lab for Listening with Yuri Zaitsev.

From day one, we stepped into the scariness of not knowing the outcome of our projects and embraced the experimental quality of it all. Over time, we learned we didn’t actually have to know where we were going with our work. We have gained comfort with the messiness of praxis and a sense of wonder in trying a range of ideas out and watching, like children, how they play out. By paying very close attention to what is unfolding in front of us, and adapting accordingly, we have discovered things we could not have imagined when we started out.

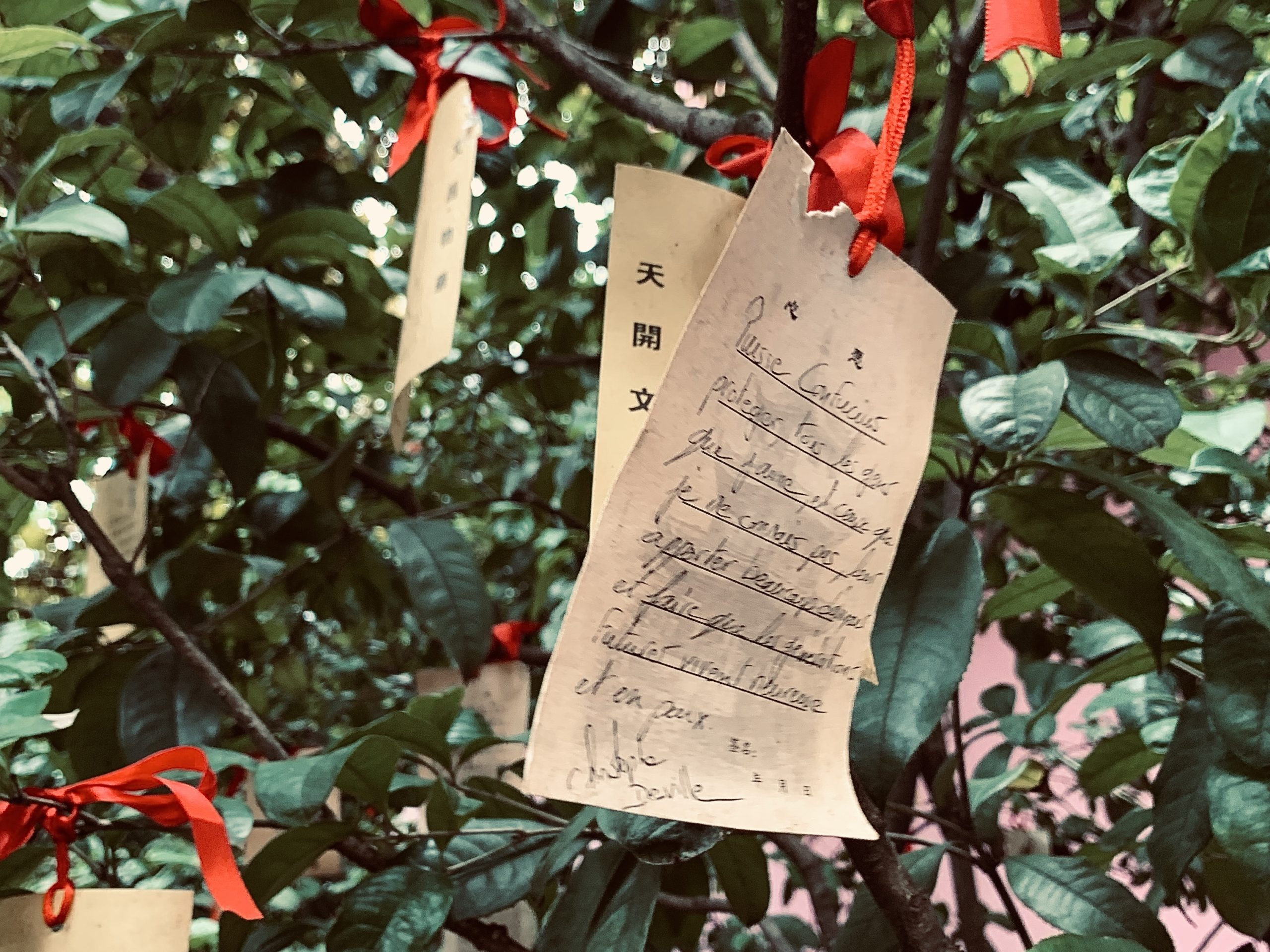

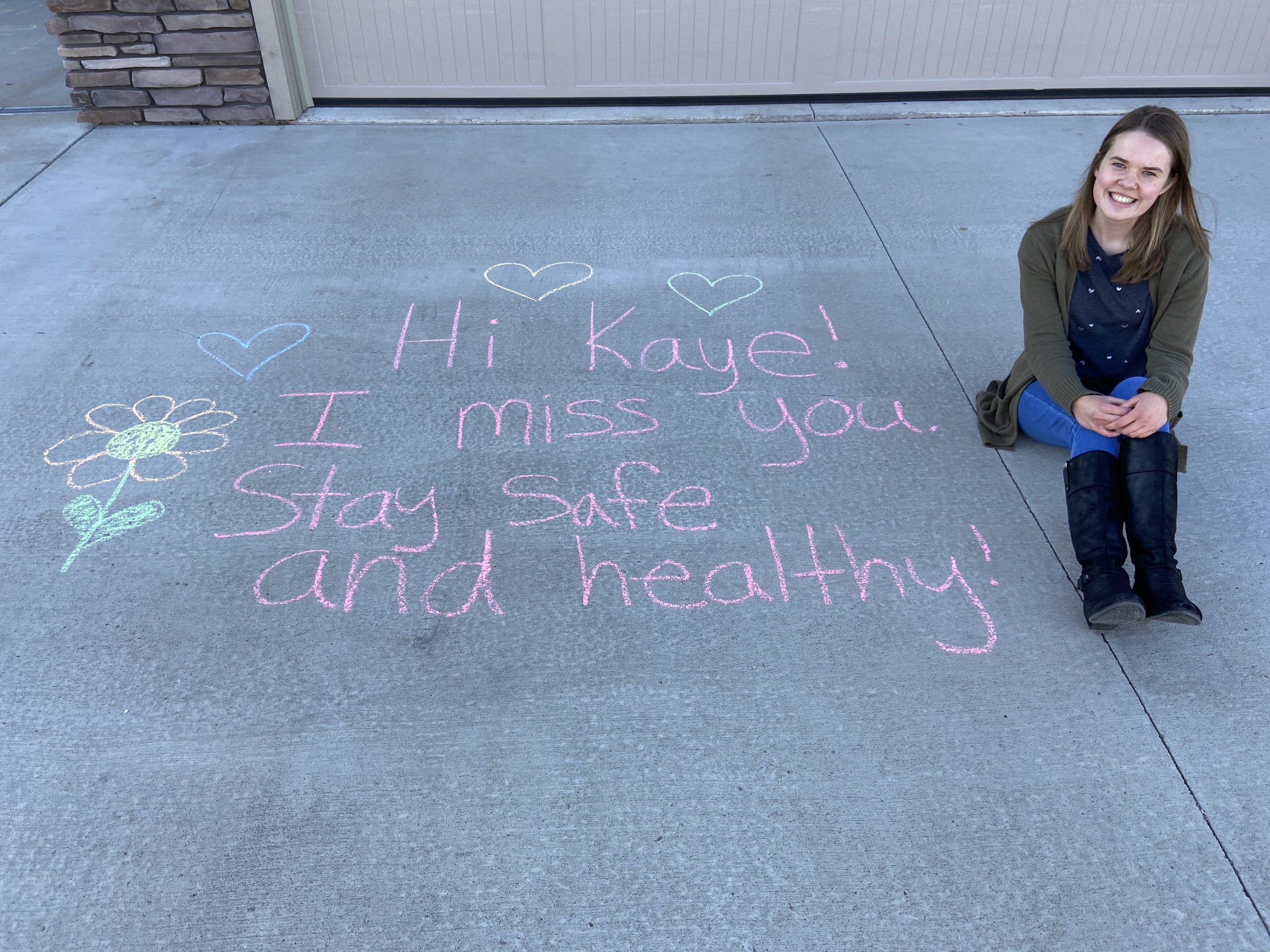

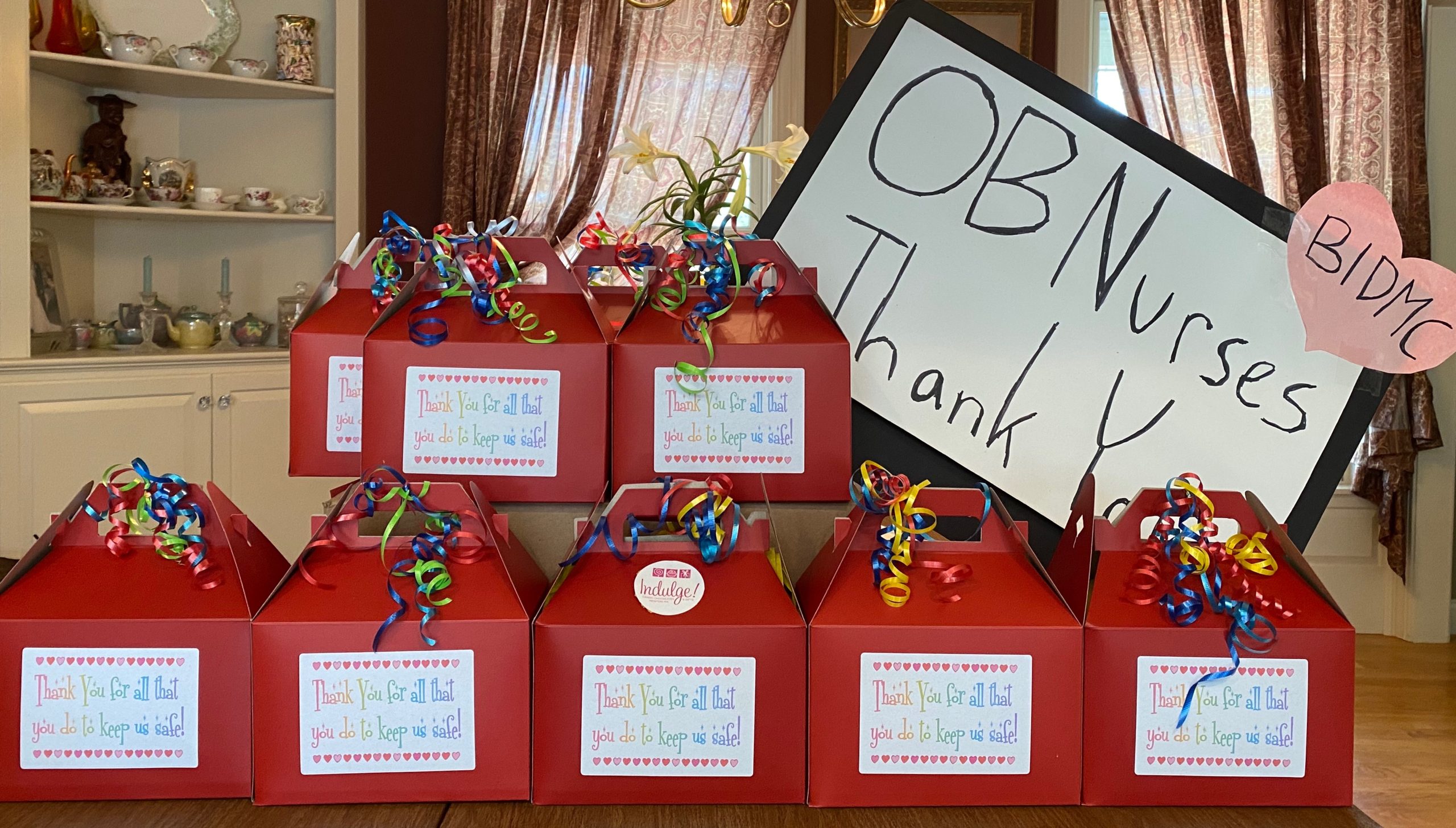

In terms of kindness, for me stepping into the unknown was made possible because I was held by my community. Three friends who belong to the Dark Skies feminist ethnography collective encouraged me to pursue my desire to facilitate spaces for writing that centered safety and pleasure. One of my friends told me when I was starting my coaching practice: “You matter too much to me to let you fail, so take your risks, and we’ll face it together.” Another friend said to me, “As long as I walk this earth, you are not alone.”

It was my friends’ faith that I should follow my own “yes” that enabled me to do work that supports the people I coach and teach in following theirs.

To learn more about Nethra and her work, please visit The Listening Lab.