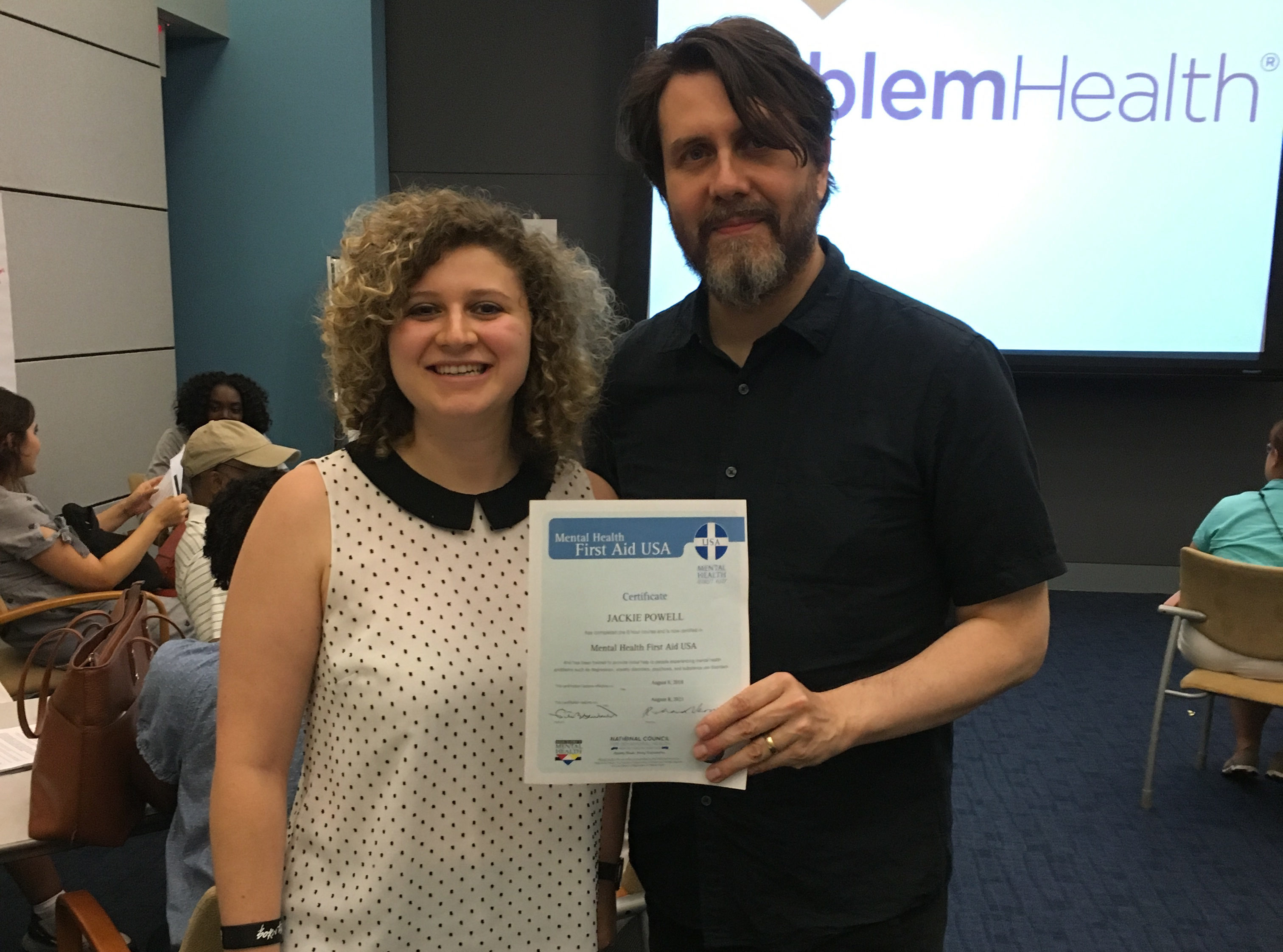

David B. Smith is CEO of X Sector Labs and currently working with the State of California’s Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission to create an incubator for mental health innovation. He is also the husband of Maya Enista Smith, BTWF’s Executive Director.

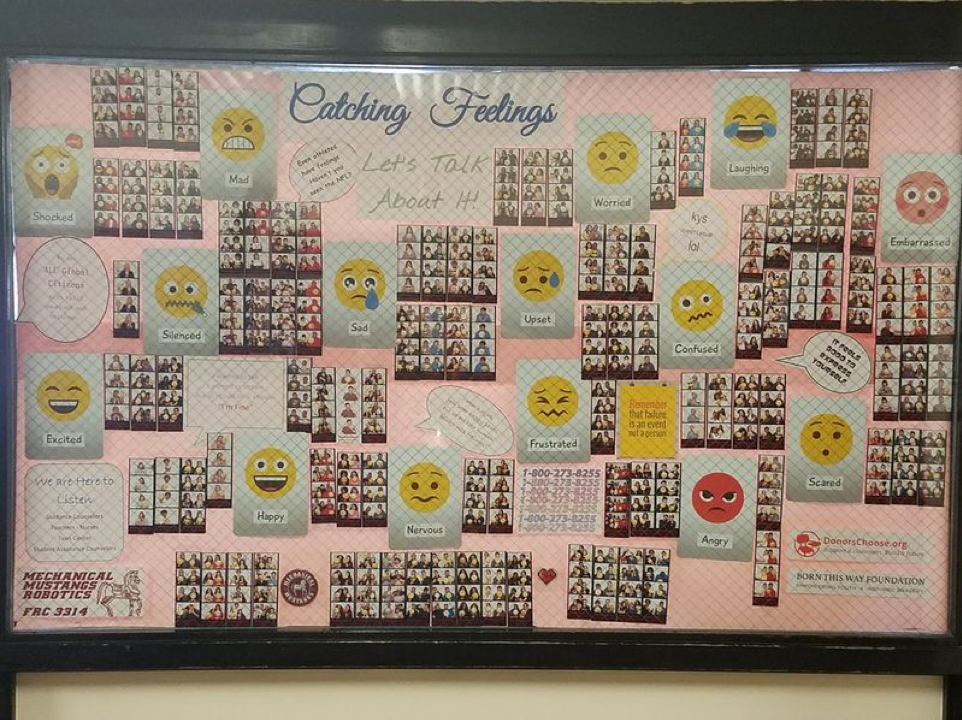

Today’s blog discusses suicide which may be triggering to survivors or to the family and/or friends of victims. If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, please seek help. You can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 24 hours a day or reach out to one of the other resources listed below for assistance.

“I’m sorry to put you through this Dave. I love you. HOOAH.”

Ping! This text woke me up on January 25, 2009. It was from my Dad, and I knew exactly what it meant. I was about to lose my father.

I called him back immediately, and the phone went straight to voicemail. I cracked open my laptop and began a very personal game of Carmen Sandiego. I logged into my Dad’s bank accounts and credit cards to track their last use. To my surprise, I saw a week worth of charges migrating east from Phoenix (where he was living at the time) to Washington DC (where I was living at the time). Was he outside?

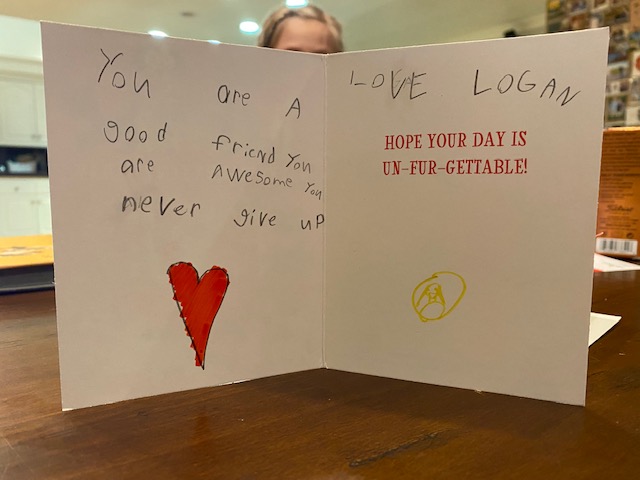

I slammed my computer shut and ran out my front door, hoping to find him sitting on my stoop. He was not. I looked up and down my street hoping to see his British Racing Green Jaguar parked nearby. It was not. I walked down the block to Logan Circle praying to see him sitting on a bench. That prayer was not answered.

I went back inside, signed up for a Zipcar, loaded my puppies in the backseat, and proceeded to circle my Dad’s favorite DC spots like a hop-on / hop-off bus, from the Tidal Basin and the Mall to Arlington National Cemetery.

Out of ideas, hope, and tears, I returned to my car and drove home. I walked through the door, went to my room and laid down. The moment my head hit the pillow, a disruptive knock shook my door and the whole apartment. I jumped up, ran to the door, swung it open, and was never the same.

Two DC police detectives stood in my threshold and simply asked, “Are you David B. Smith?” Inside, my heart burst and fell to the floor sobbing. Outside, I felt like I was in a cameo of Law and Order and welcomed the detectives into the house. They fumbled for a minute trying to the find the words until I blurted out, “Did you find my Dad?”

“A king, realizing his incompetence, can either delegate or abdicate his duties. A father can do neither. If only sons could see the paradox, they would understand the dilemma.” – William Shakespeare

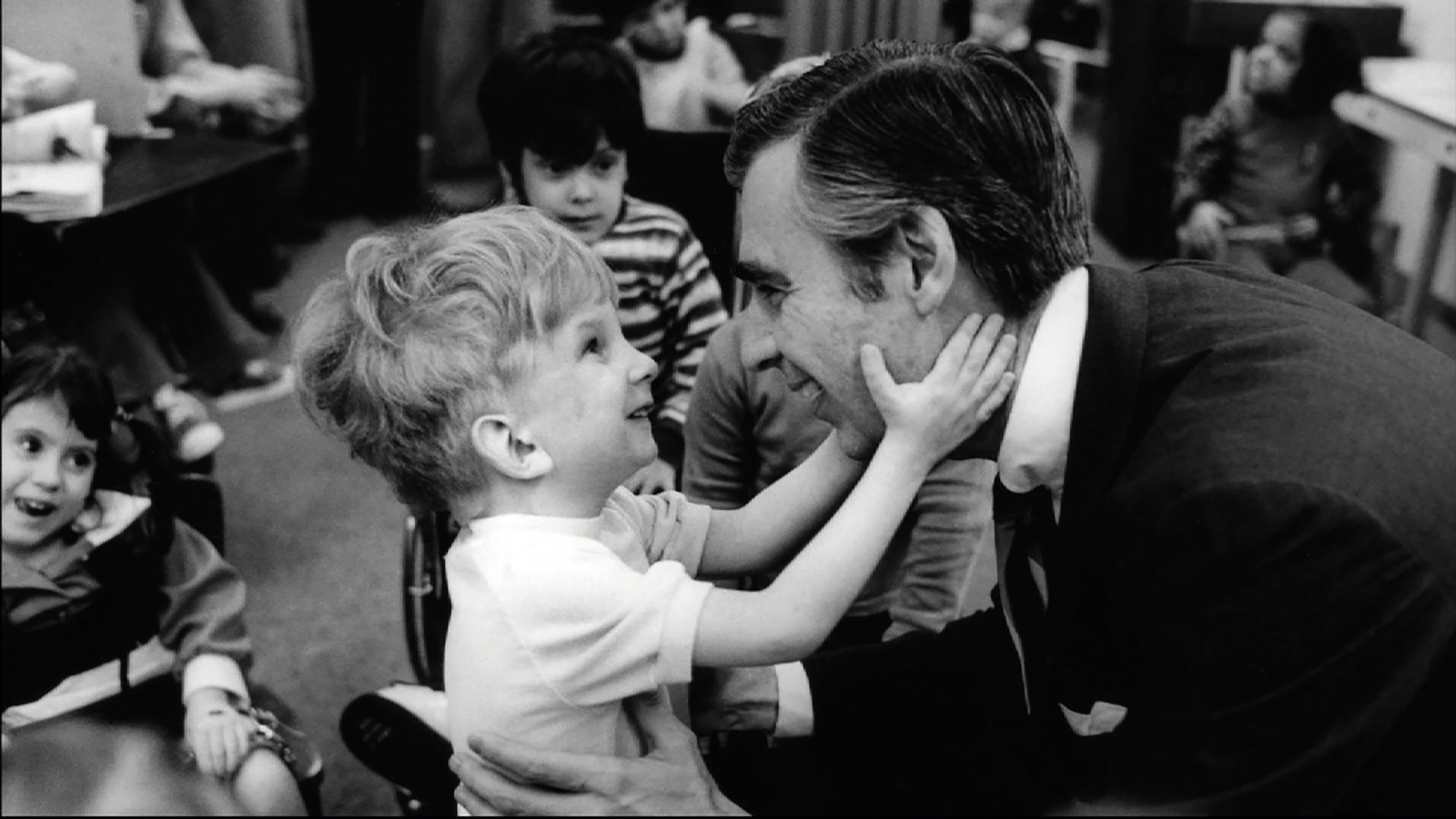

Relationships between fathers and sons have been complex since the dawn of time. Books have been written about why and wars have been fought over it. From my experience, a root cause of this revolves around the seeking and granting of approval – in other words, are you making your dad proud (and will he ever tell you)?

Striving to make my Dad proud was a core motivating factor of many of the triumphs and failures in my life. No matter what I accomplished, the awards I won, the sports I played, it always felt his approval was just out of reach. As a dad now myself, I understand that you always want your kids to be better, to excel, to improve, and to realize their full potential. You want them to accomplish more than you ever could, and this can manifest by holding the worm of approval just out of reach as they leave the nest and spread their wings. However, offering validation for effort and results doesn’t hinder progress, it accelerates it.

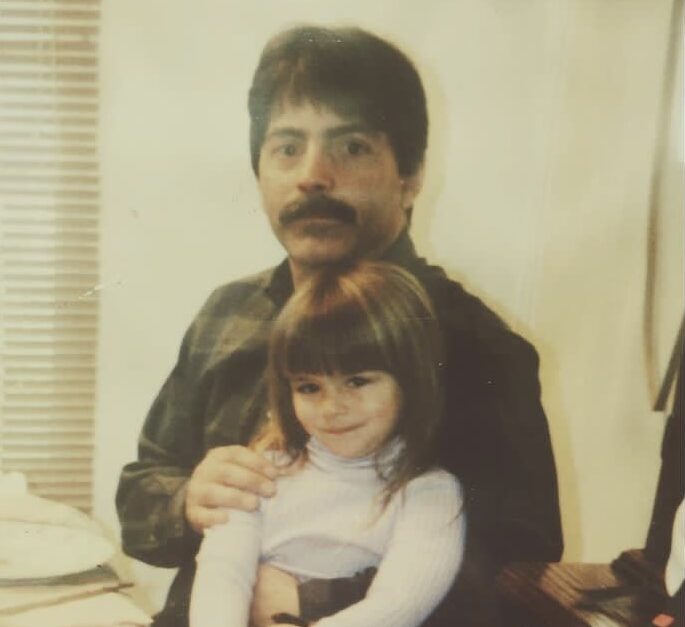

My Dad grew up in poverty, moving regularly, often food insecure, and occasionally homeless. He had a working father, three brothers, and a mother with mental illness. My Dad was a brilliant man. Growing up in the Sixties in California, he had various paths ahead of him but only one true calling. While others were burning their draft cards, he dropped out of high school to join the Army and volunteered for Vietnam. Serving our nation in uniform was an honor and responsibility, a path his father, his father’s father, and his father’s father’s father had followed. Ultimately, he wasn’t sent to Vietnam, yet he served in uniform for two decades.

My Dad retired after 20 years of military service when he was just 39 years old. In the Army, he found comradery, challenge and purpose. Beyond the armed forces, he struggled to find any of those, except through raising his children. He tried law school, journalism, disaster relief, retail, and banking. The lack of pride and purpose he found through his encore career was compounded with growing mental illness.

Growing up, I thought my Dad was half superman and half jerk. At times, he was the most interesting man alive, telling unbelievable stories, dispensing sage advice, speaking numerous languages, schmoozing the room, and taking our family on adventures around the world. Other times, he often felt the world was out to get him and most human interactions were veiled or transparent assaults, and various triggers would send him into spirals of rage. As kids we learned to step carefully, bask in the good days, read his mood, and tune out the yelling when necessary. This was my Dad and my guidepost for all things masculine.

It wasn’t until years later that I came to understand that he was a diagnosed manic, bipolar schizophrenic. While understanding this diagnosis, and more broadly mental health and illness, didn’t excuse the pain his behavior sometimes caused, it did help to provide context. He was fighting a daily battle with the demons in his head and we could only get a glimpse to the status of that battle when he allowed us in.

“All the times that I cried, keeping all the things I knew inside…If they were right, I’d agree, but it’s them they know, not me. Now there’s a way and I know that I have to go away.” – Cat Stevens, Father and Son

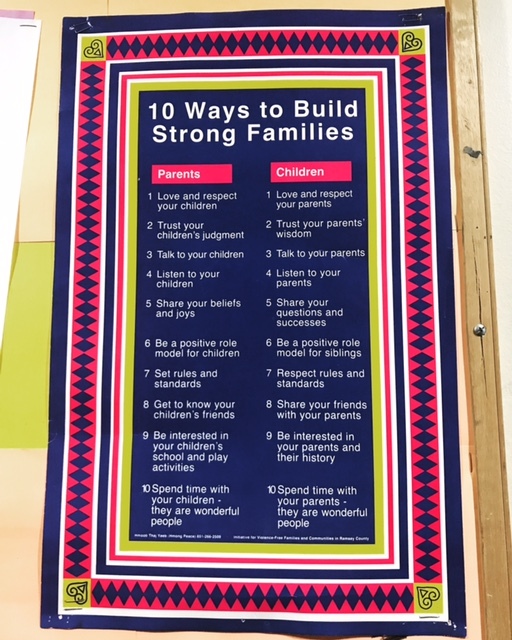

Reflecting back on my relationship with my Dad, I now realize more than ever that healthy relationships are two-way. We both need to give to the other to make the relationship fulfilling. While we understand this in healthy marriages, we often view parental relationships as one-sided with the power, learning and teaching all coming from the elder.

My Dad used to play me Cat Stevens, much more “Father and Son” than “Cats in the Cradle.” He loved the line when the father says, “You’re still young, that’s your fault, there’s so much you have to know.” This often preceded a several hour lecture where he dispensed advice based on his own meandering experiences. A father’s job is to teach, while learning can be viewed as weakness. This inherently puts the father’s known experience in a position of ultimate truth and leaves little room for mutual growth.

As I grew older, our relationship began to change and adapt – from the first time I beat him at chess to graduating from college to winning awards for my social entrepreneurial endeavors – and he began to shift from sage on the stage to explorer along my side. In his own self-debasing way, he’d offer the saying, “You can always use me as an example of what not to do.” He also would add, “The hardest day in a son’s life is when he realizes his father is just a flawed man.”

I miss my Dad every day. I miss how he made me laugh. I miss his lectures. I miss our witty banter. I miss traveling with him. I miss debating politics together. Above all, I miss him when I can’t share a new memory, milestone, or realization. I can’t tell him that he was right. I can’t tell him when he was wrong. I can’t share a video of his grandkids singing patriotic songs. I can’t invite him to go to sporting events. I can’t call him after getting a new job. I can’t call him when I screwed up and pissed off my wife. I can’t tell him I take back hurtful things I said. I can’t tell him I forgive him for those he said. With all his flaws, demons, and rage, I want these moments back and wish he was still here.

If given enough time and humility, our relationships with our fathers complete a cycle. We worship and idolize, we seek flaws and hypocrisy, we embrace and empathize, and we teach and learn together. In the end, Dad needed my pride and approval as much as I needed his. He needed my validation and unconditional love. While he may have known deep inside, I should have said it more. I should have told him and shown him how much he meant to me.

“Pride is not the word I’m looking for…there is so much more inside me now.” – Dear Theodosia

Relationships with fathers are complex, especially when complicated with divorce, lost trust, alcoholism, disappointment, mental illness, lack of accepting who we are, or any other divisive experiences that drive us apart. Not the least of these is realizing our dads are just flawed human beings like everyone else. While our childhoods may have shattered with the realization that the superhero cape was just part of the costume alongside the jolly red velvet, our relationships can deepen through empathy, understanding and a little grace.

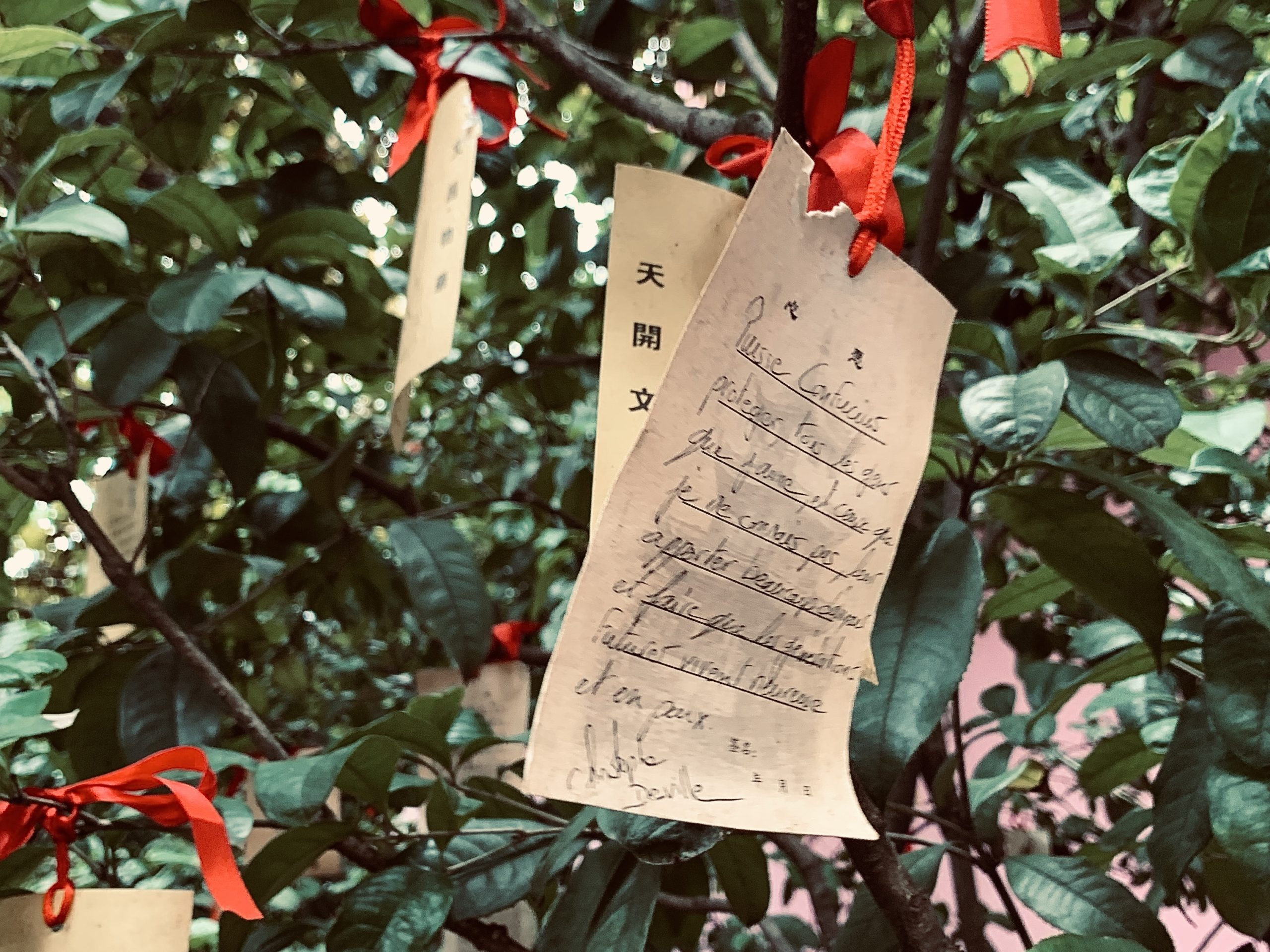

For those who still have a dad present in their lives this Father’s Day, I encourage you to tell him that you love him, tell him your life would never be the same without him, tell him you need him, tell them you are there for him, tell him all of the amazing things he does to make you feel special, tell him you forgive him, tell him you see who he is, and then tell him that you are proud of him.

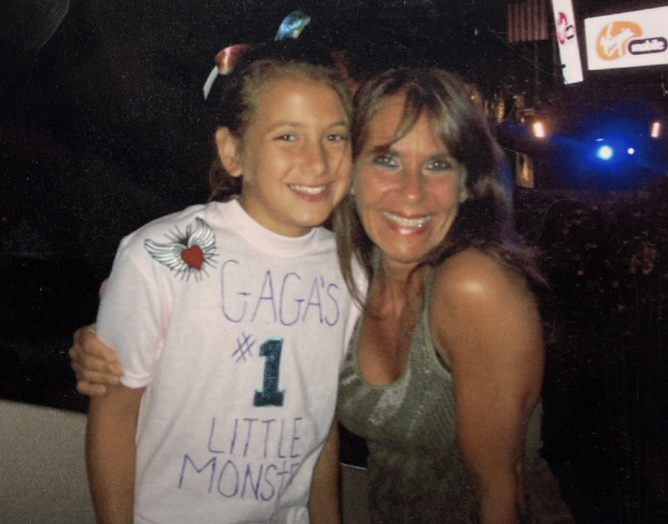

For me, I will focus on my son and daughter and begin the day telling them how proud I am of them. I will do my best to wear the cape and be the superhero they envision me to be. However, I will also tell them (and show them) that their Dad has and will fail. I will ask for their grace. I will strive to never let them down, and I will ask forgiveness when I inevitably do. I will try to be humble and treat them as equal members in our relationship. And, I will do everything I can to live a life and be a Dad that will allow them one day to say, “I’m proud of you…Dad!”

- Get Help Now Resources: https://bornthisway.foundation/get-help-now/

- Suicide Prevention Center Hotline: (800) 273-8255

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741 in the United States

- American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: https://afsp.org/find-support/