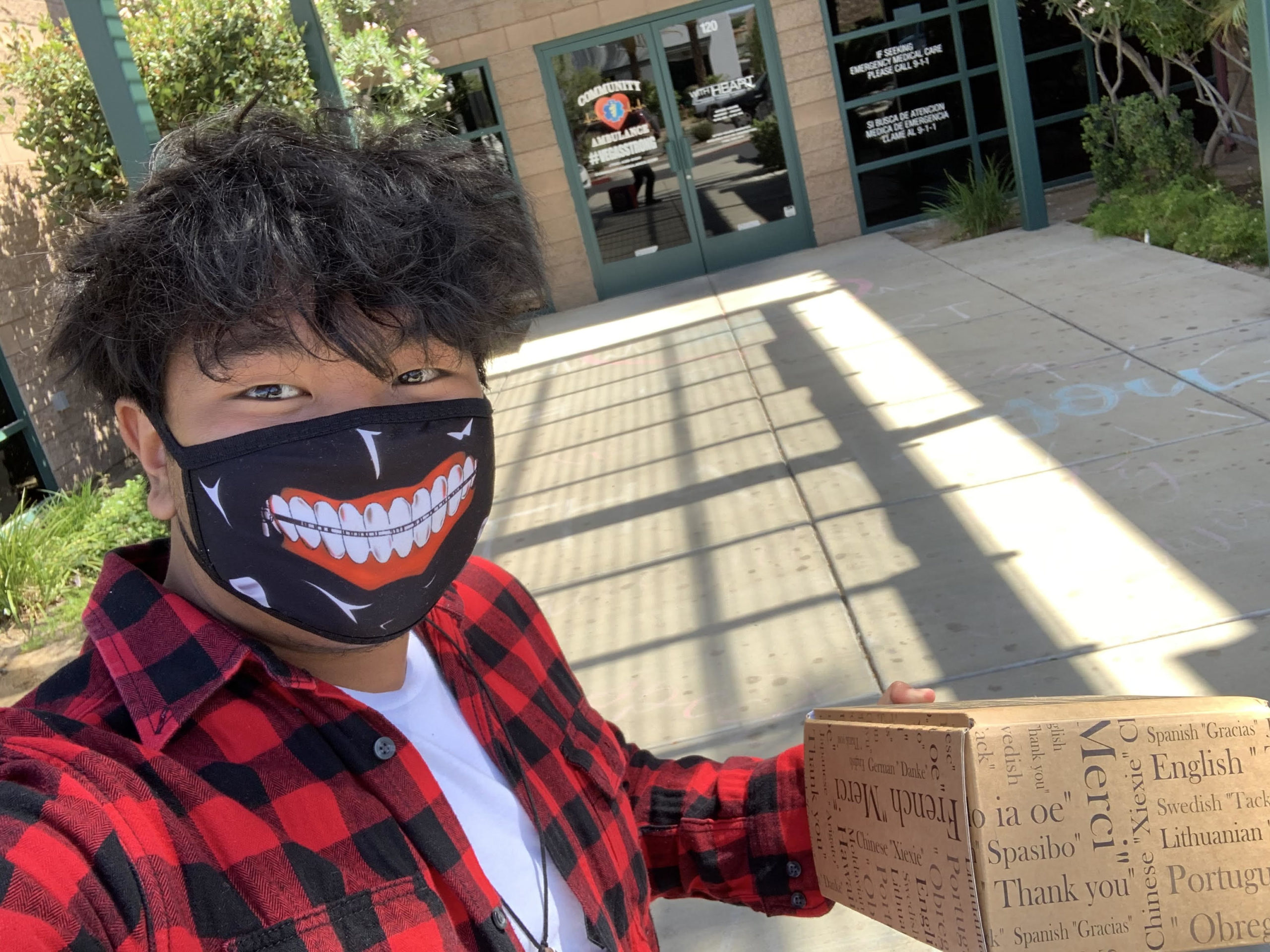

Most people in my life generally only know me by six characteristics: I am a California native, I am a college student at the University of Pennsylvania, I like psychology and brains, I play the bassoon for fun, I enjoy games, and I am passionate about mental health. All of these are some examples of the nice, lighthearted parts of me that make up my mask.

When taken at face value, all these aspects sound like things that can help other people get to know me. They are nice details about myself I can share with people to make conversation entertaining and enjoyable. A majority of people I come into contact with in my daily life are

generally, content knowing just those details about me.

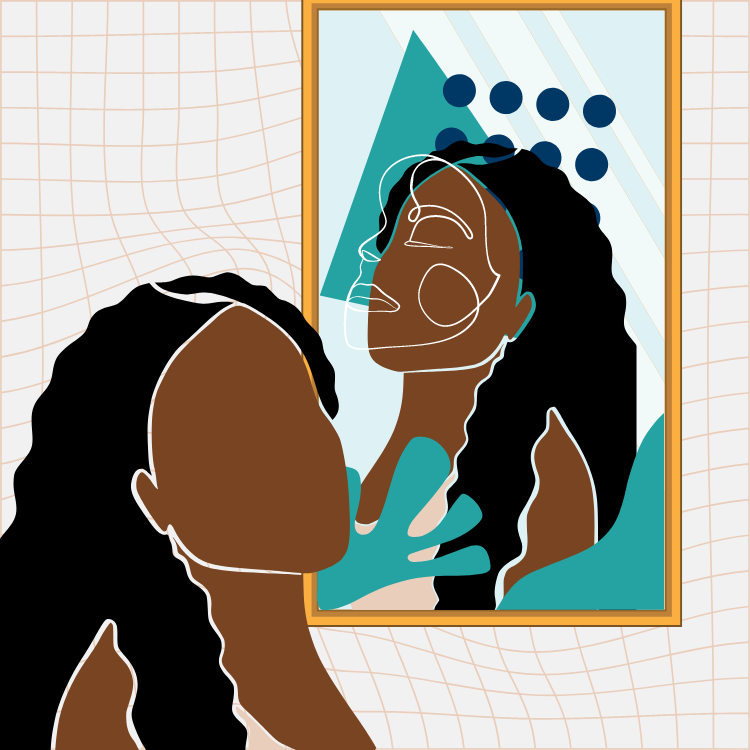

To most people, I am just a quiet and easygoing guy who seems more-or-less like a normal, decently put together college student. There are other sides to myself, however, that I am incredibly self-conscious about projecting.

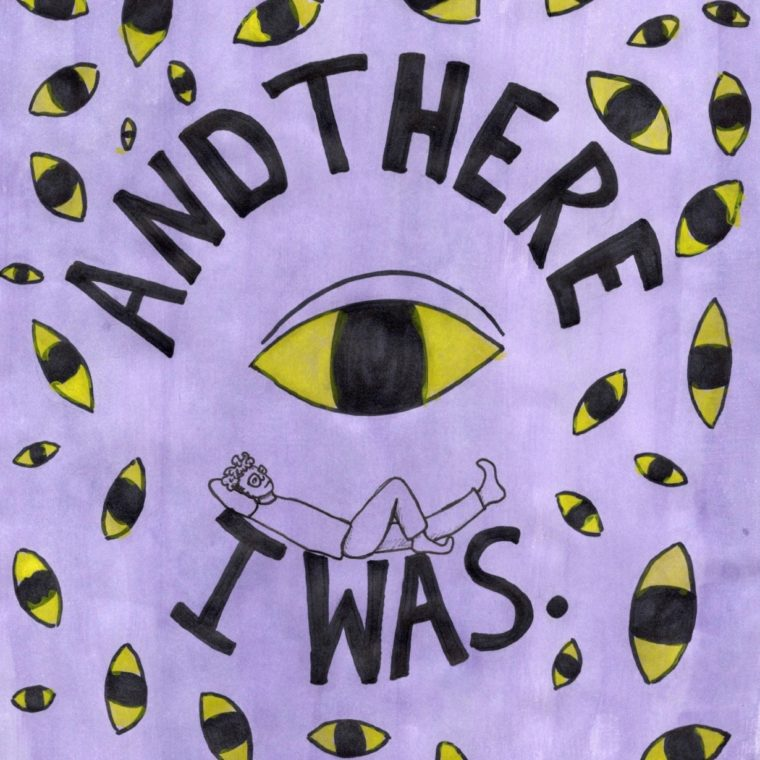

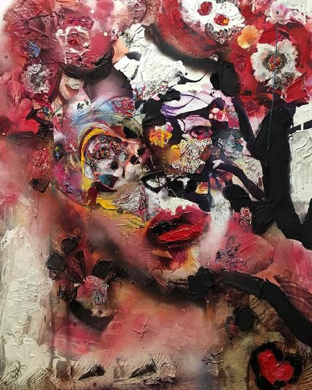

Underneath all of the friendly lighthearted characteristics lies other innate parts of me that I am always tempted to hide behind a mask: the me that is self-conscious for having absolutely no idea of what I want to do with my life in five years when everyone around me seems to have their life together; the me that stays locked in my room during bouts of anxiety; the me that suffers through self-inflicted loneliness and isolation that comes with depression.

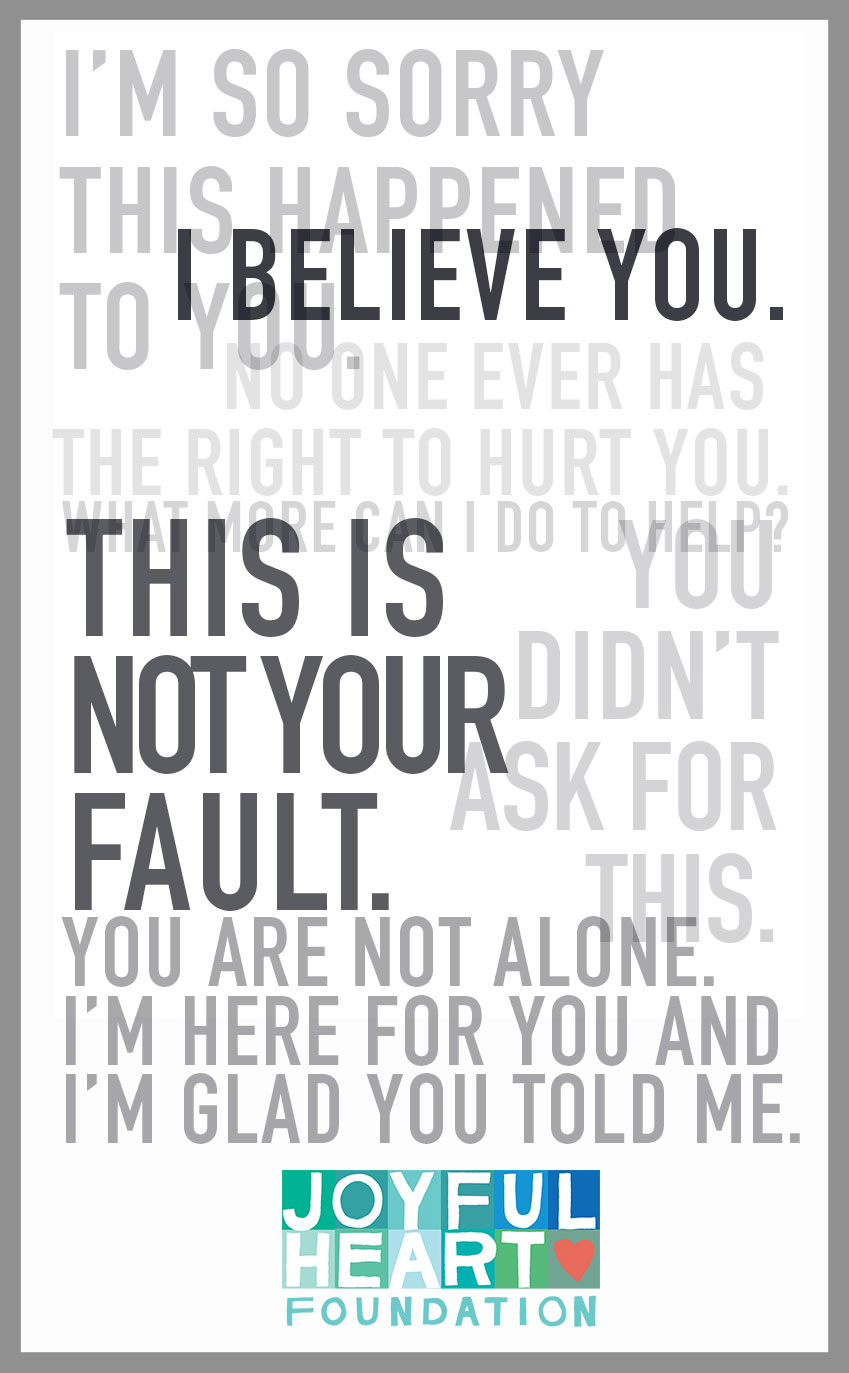

I am afraid of showing these sides of myself to other people because they are ugly and unsettling. Nonetheless, they are still undeniably parts of me. During the few times I have admitted these negative parts outside of therapy, I have often been met with skeptical comments that sound something like, “Oh, but this isn’t really you, Brian. It’s all in your head. you will get over this. Your depression doesn’t define you…”

Sure, these statements may come out of good intention and concern for my overall well-being. But whenever I hear these statements, I feel like the lack of honest acceptance is a sign that I should brush the darker parts of me under the rug.

People look down on those parts of myself because they aren’t characteristic of a respectable well-adjusted person. I seldom feel understood whenever I open up, and usually end up feeling worse for inconveniencing people by having them listen to my negative emotions. I know that the dark side of me gives my life meaning and substance, but I fall into a negative feedback loop of always hiding it and feeling misunderstood.The most heartbreaking part of this whole notion of hiding behind a mask is that I live behind a superficial persona that prevents people from knowing the real me.

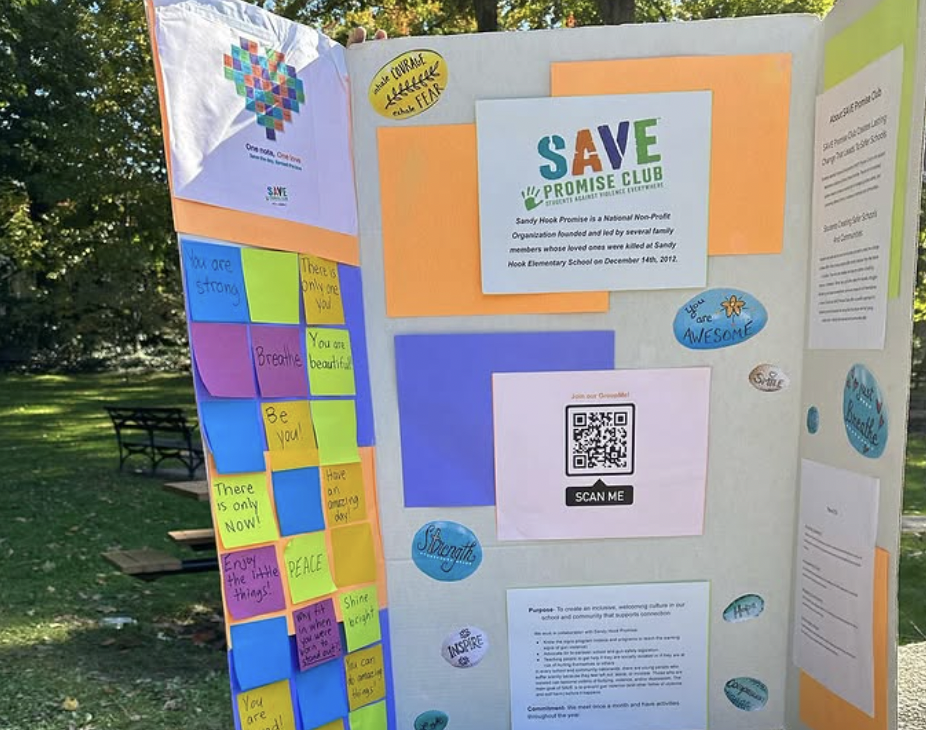

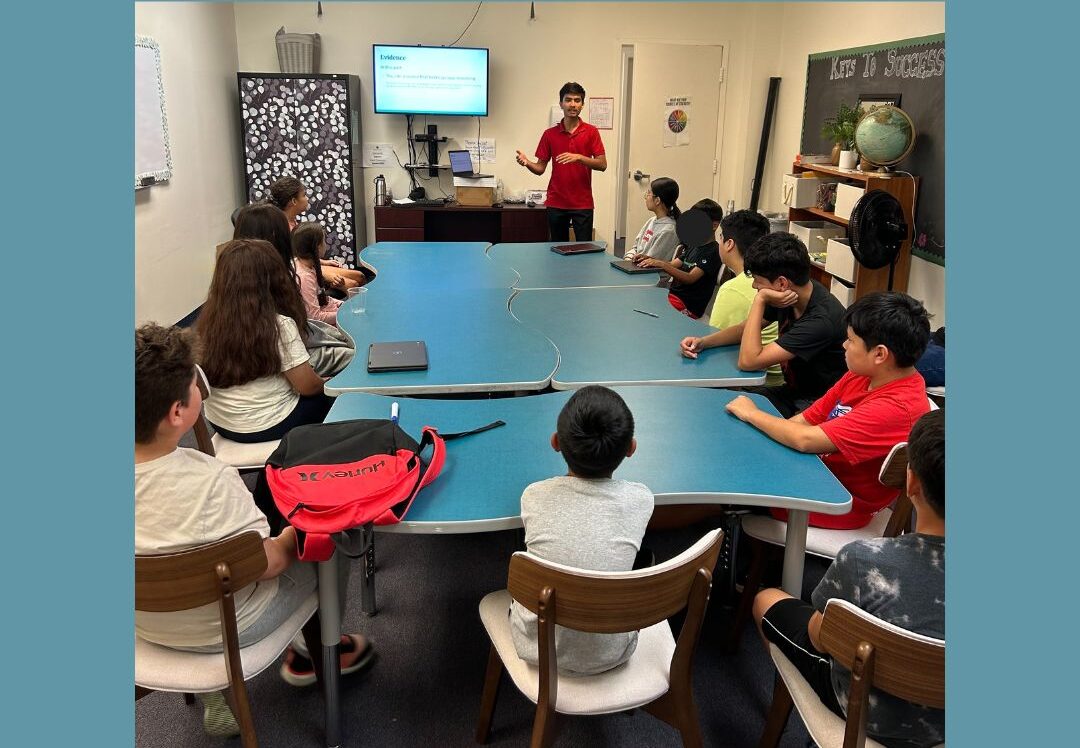

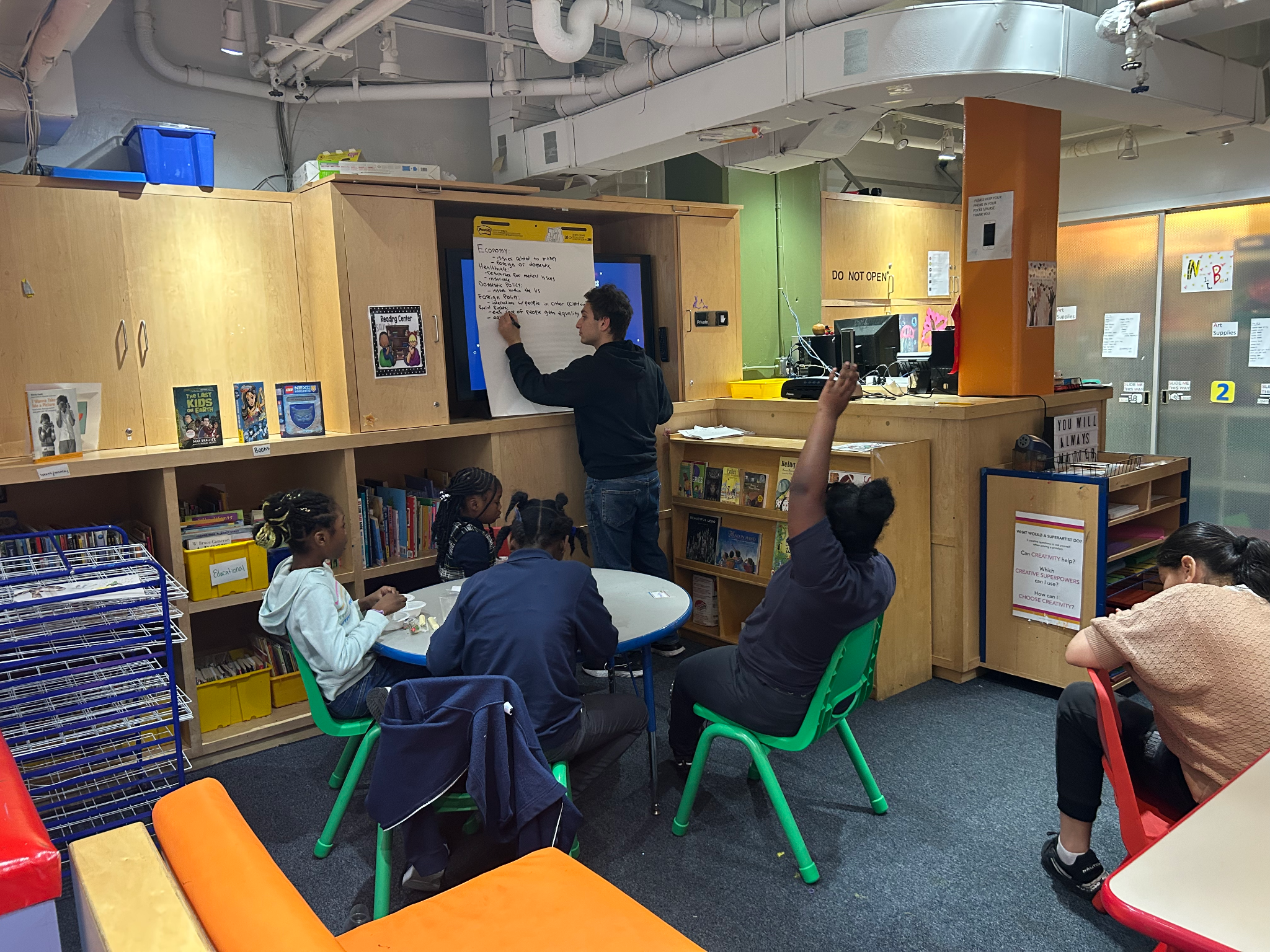

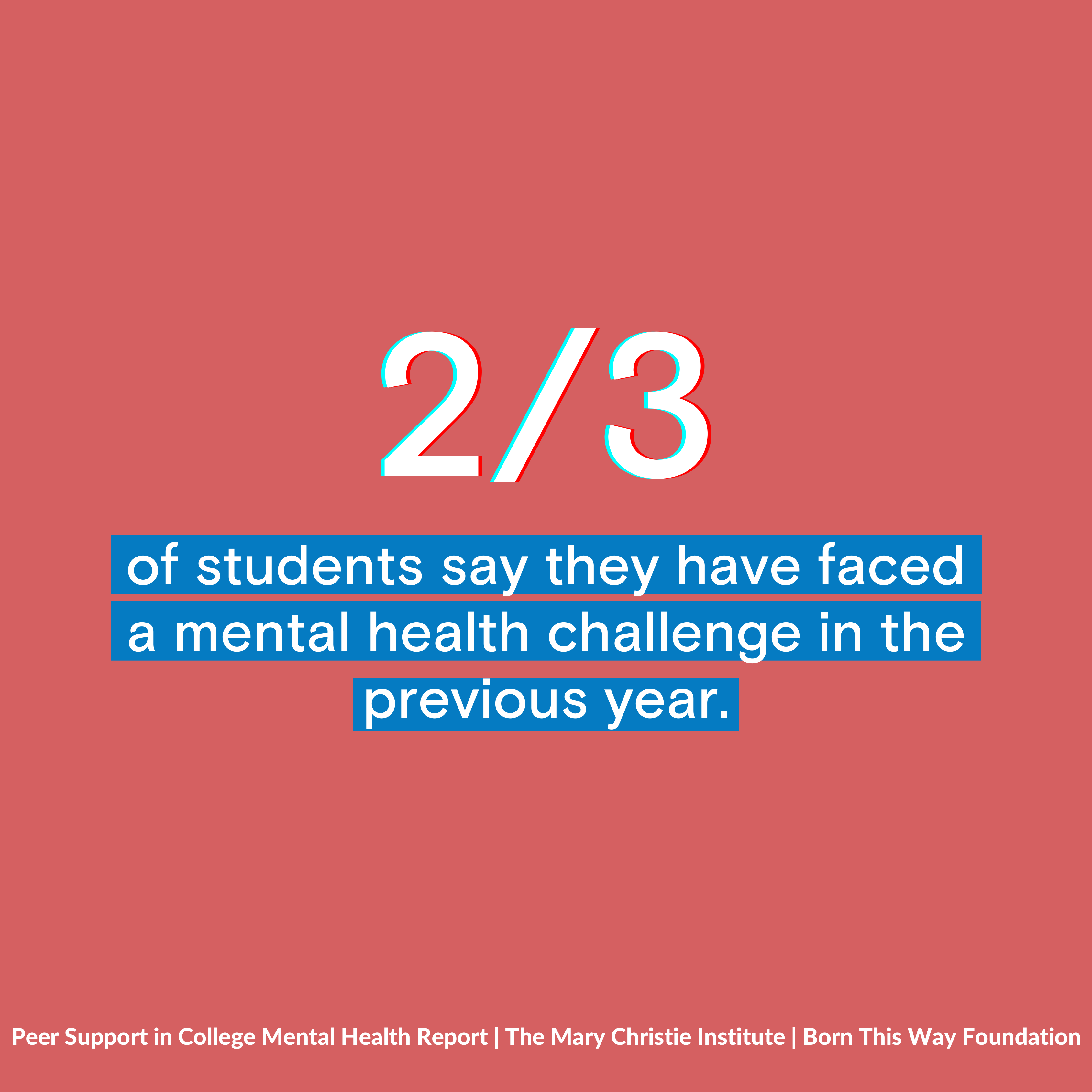

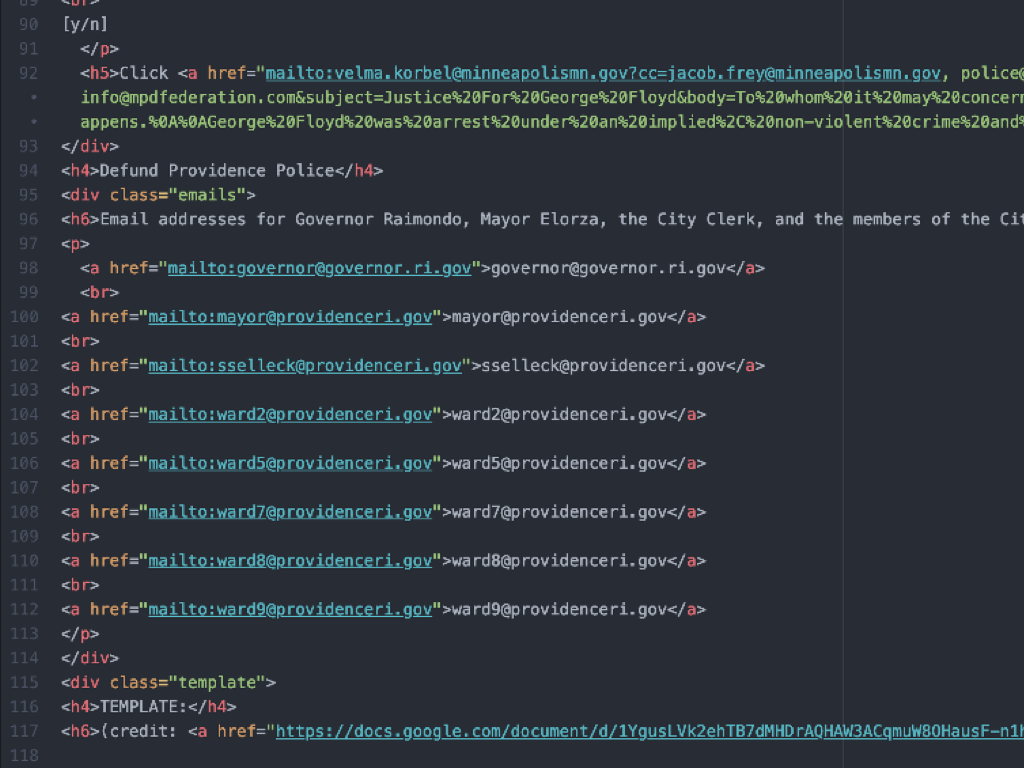

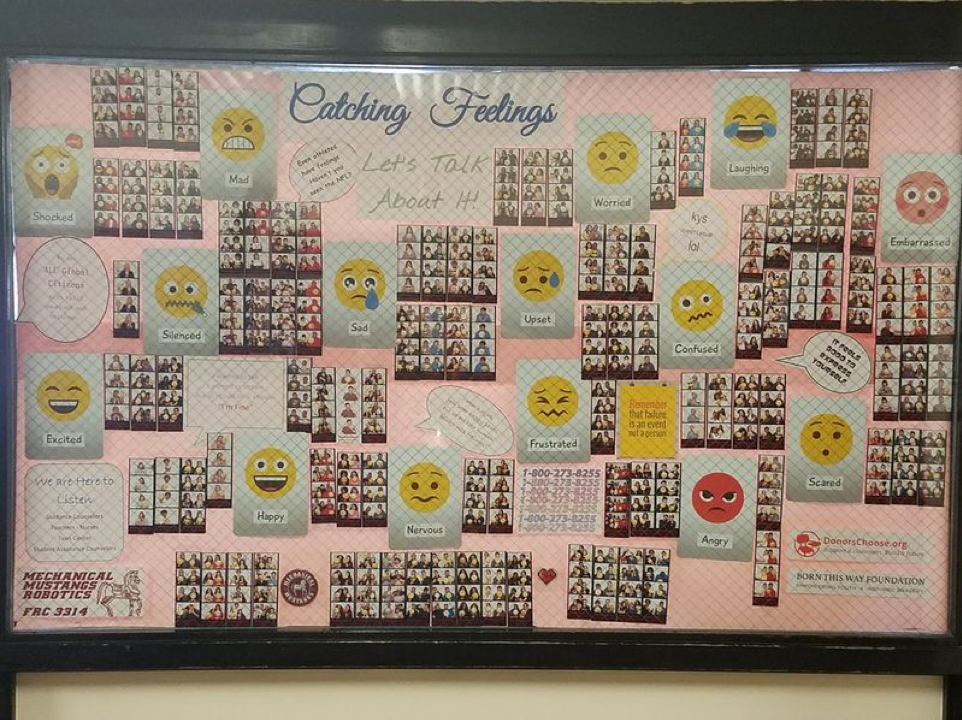

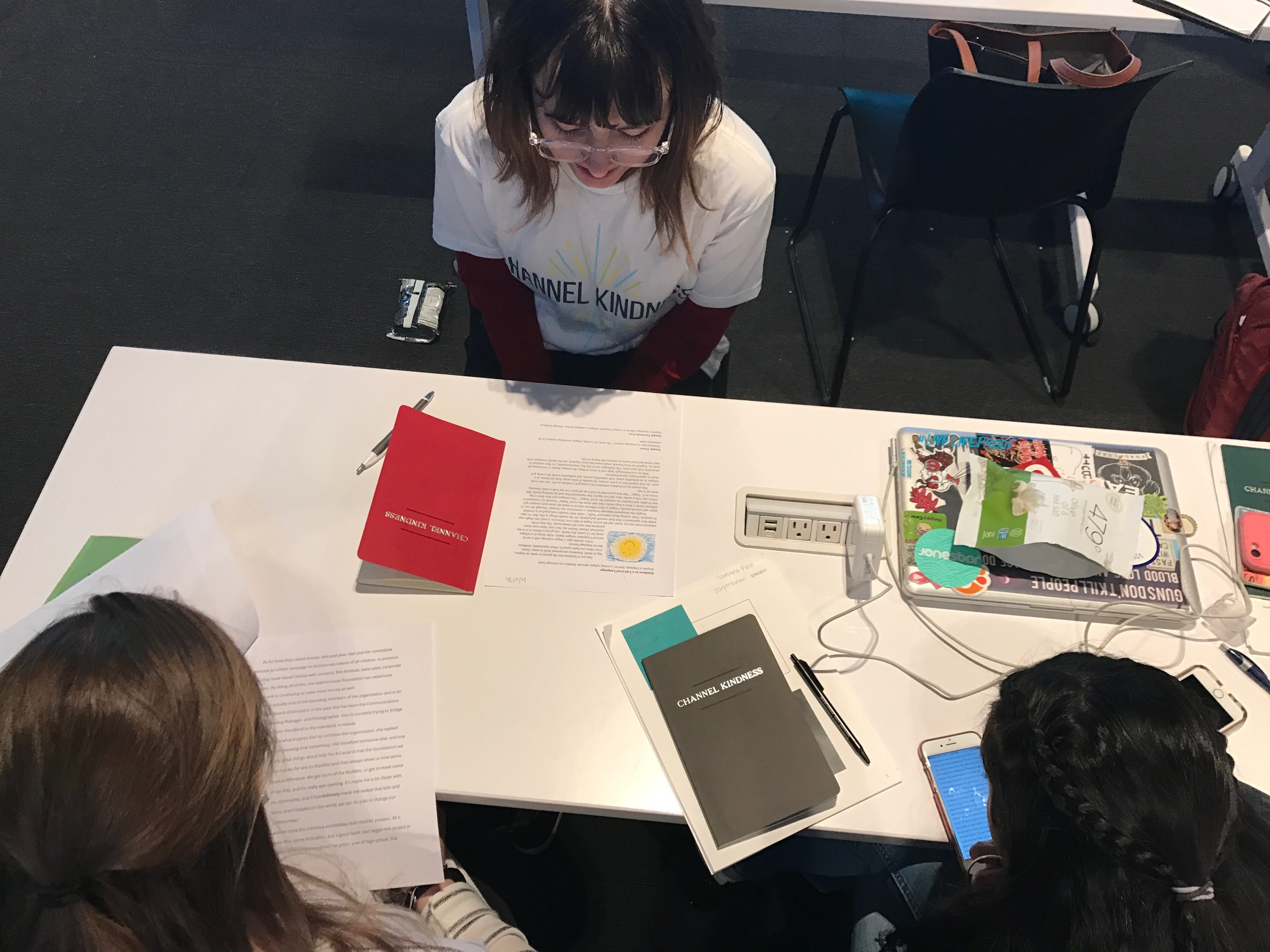

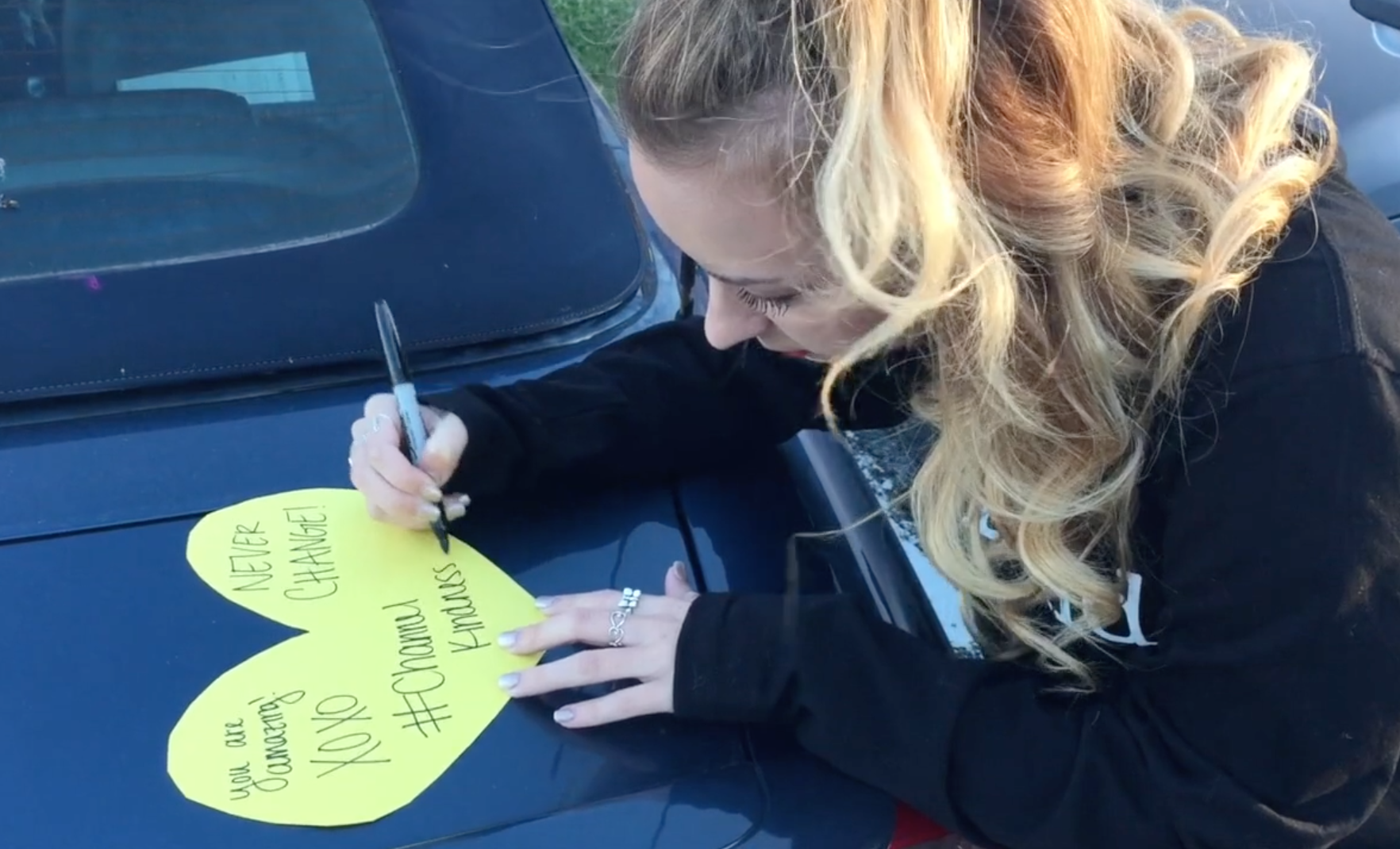

What is even more devastating is that I know I am not the only individual who does this. This phenomenon of living behind masks is especially prevalent in our culture in places like schools, workplaces, and other social environments. In schools, this urge to wear a mask is related to promoting an unrealistic portrait of personal success to your peers. In my school, this phenomenon has been dubbed, “Penn Face,” which a Billy Penn article describes as the idea of “putting on the facade that you’re perfect and your life is perfect, no matter how pressured you are to keep up with school and social life.”

An article from the Daily Pennsylvanian, UPenn’s student news outlet, documents how Penn Face can come as a result of “the need to uphold reputation” in a “breeding ground of competitiveness,” and is closely related to the wider issue of mental health. Other universities have different ways of describing this phenomenon.

A 2003 report from Duke University documented how various female students felt a need to be effortlessly perfect, smart, accomplished, and beautiful without much visible effort. At Stanford University, this phenomenon is dubbed “Stanford Duck Syndrome,” named after the idea of a duck gliding effortly across the surface of a lake, but furiously paddling beneath the surface as it struggles to stay afloat.

Taking all this into consideration, we are forced to ask the question: Why is this significant?

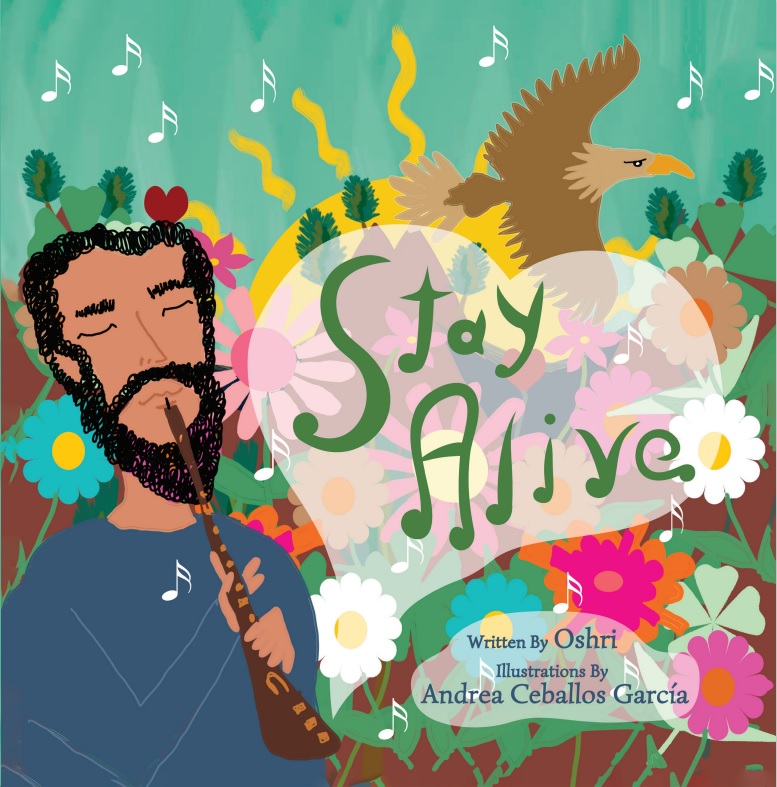

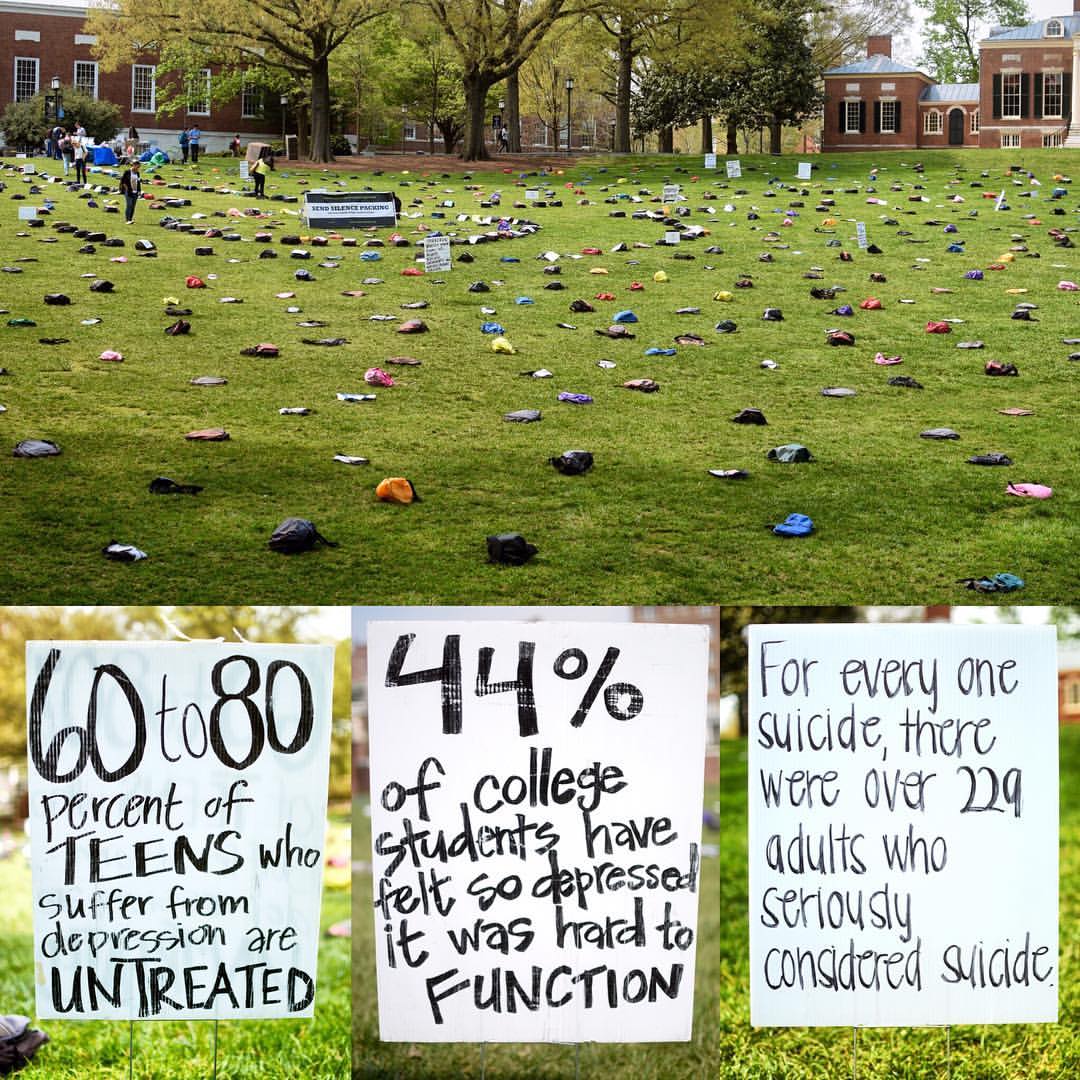

From my experience, this idea of promoting a surface-level persona reinforces an issue that we have to be perfect to be accepted. People feel tempted to only project the best parts of themselves, and the more this happens, the more others feel tempted to do the same. In the most extreme cases, this phenomenon may play a significant role in mental illness and be a major factor in driving people to suicide, as documented in a New York Times article.

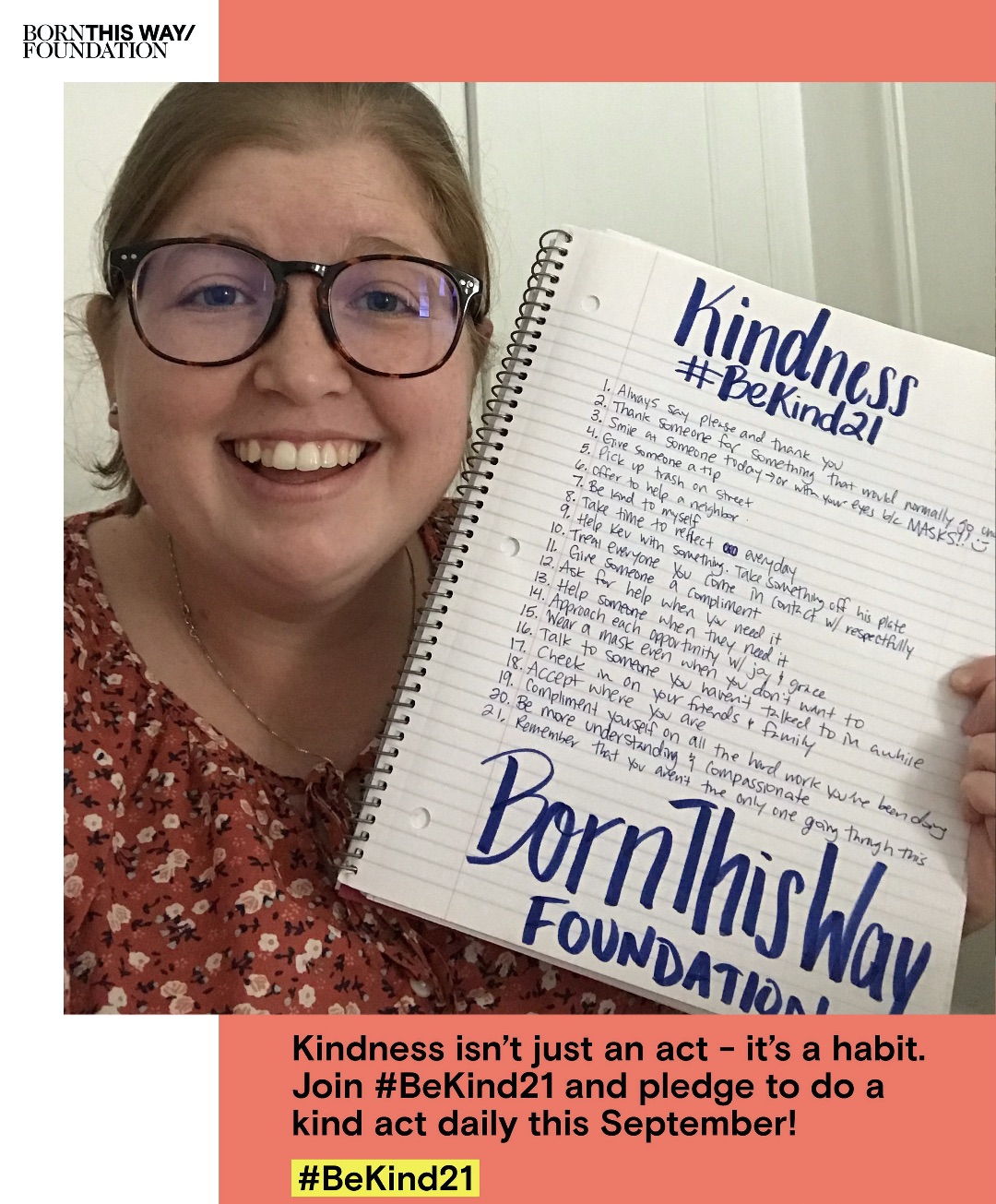

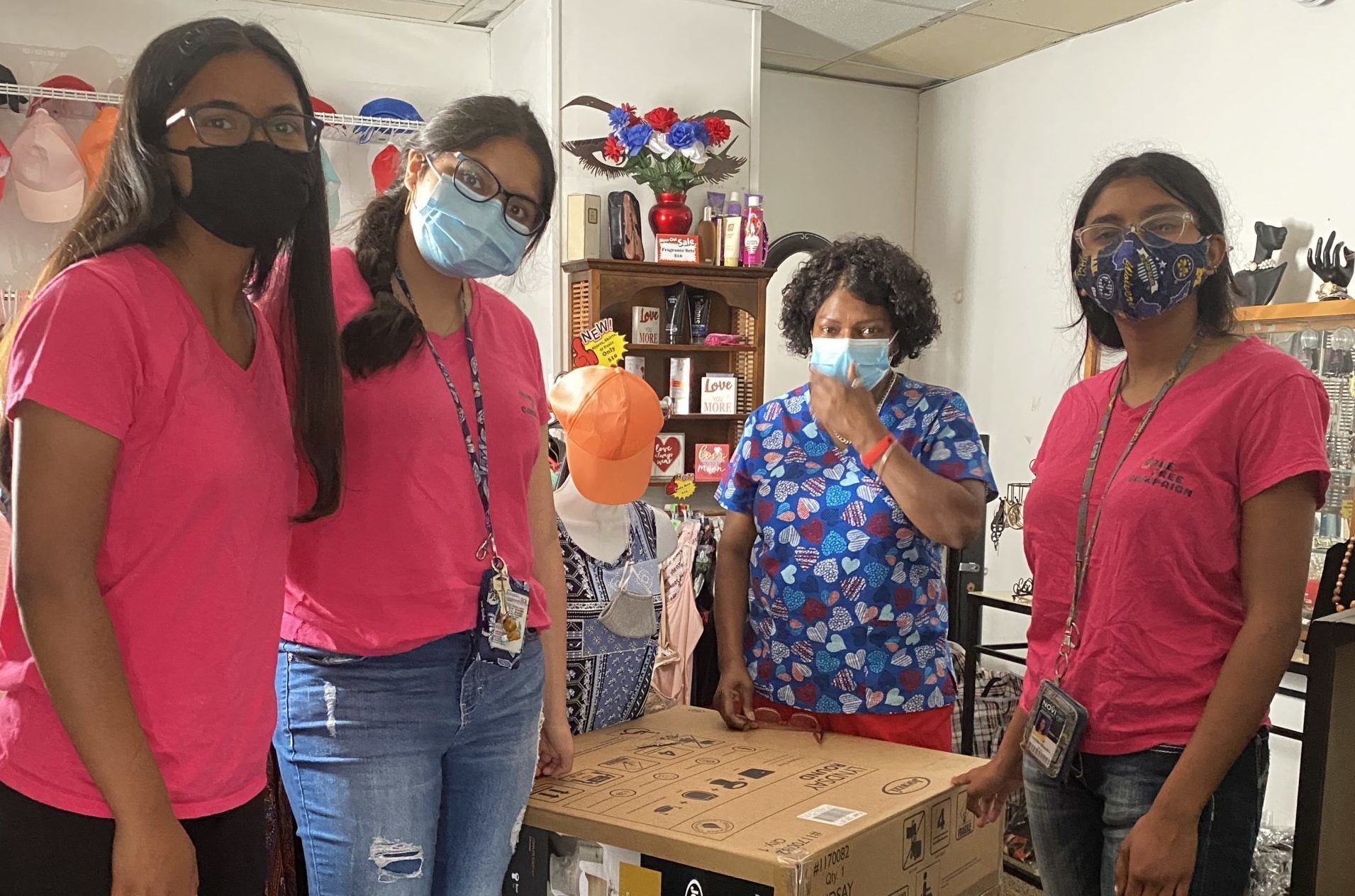

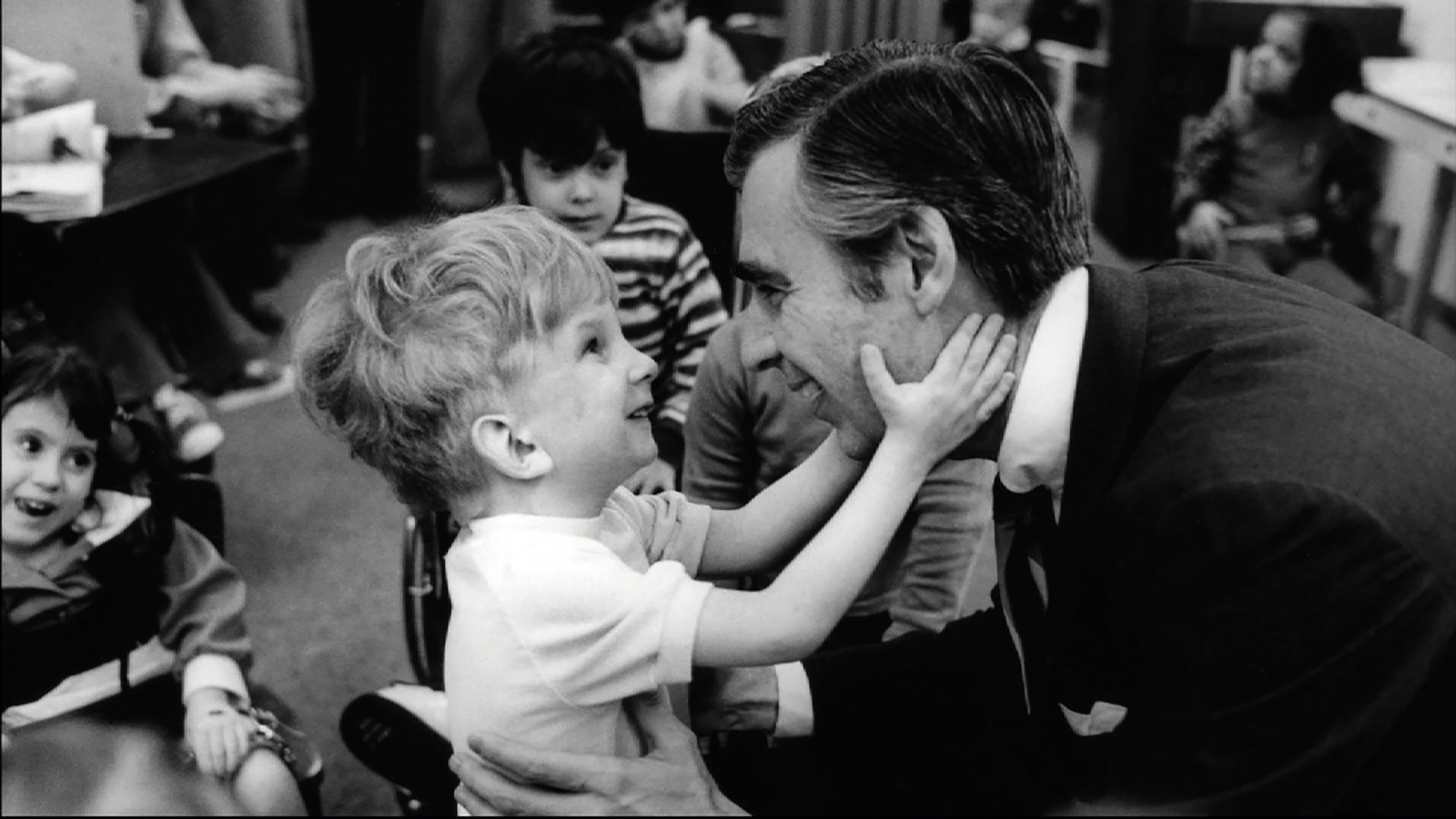

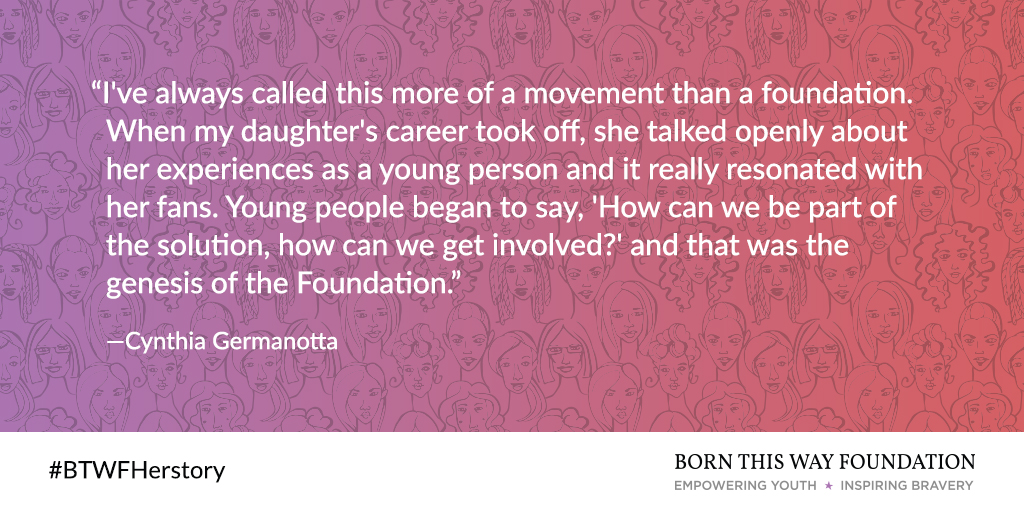

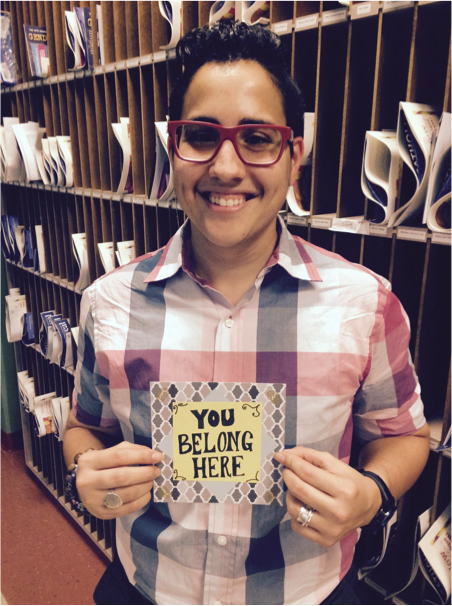

The problem that comes with projecting masks of ourselves is a serious topic we must consider. We need to catch when we fall into habits of displaying a mask out of fear to be on par with everyone else. We need to acknowledge that in many cases, “Penn Face” and “Stanford Duck Syndrome,” stem from deep-rooted insecurities that speak truths about ourselves. We then need to have the courage to confront those insecurities– in my case, I need to do a better job coming to terms with the messy underbelly of my own depression and anxiety. When it comes to changing norms about “Penn Face” and the “Stanford Duck,” we need to learn to be comfortable with ourselves and be more open, compassionate, and understanding toward other people’s lives.

All this can help us take note of what we can do to help ourselves, and by extension, the world around us. A wonderful Ted Talk by writer Caroline McHugh addresses the concept of “interiority,” the ability to recognize yourself as your own person whose life is not predicated on the lives of others. While this solution may sound easier-said-than-done, it nonetheless allows for an extraordinary liberty that paves the way for our own personal enlightenment. I hope to make it my goal to embark and continue on this journey of self-discovery, and extend my heart to all of those who wish to do the same.

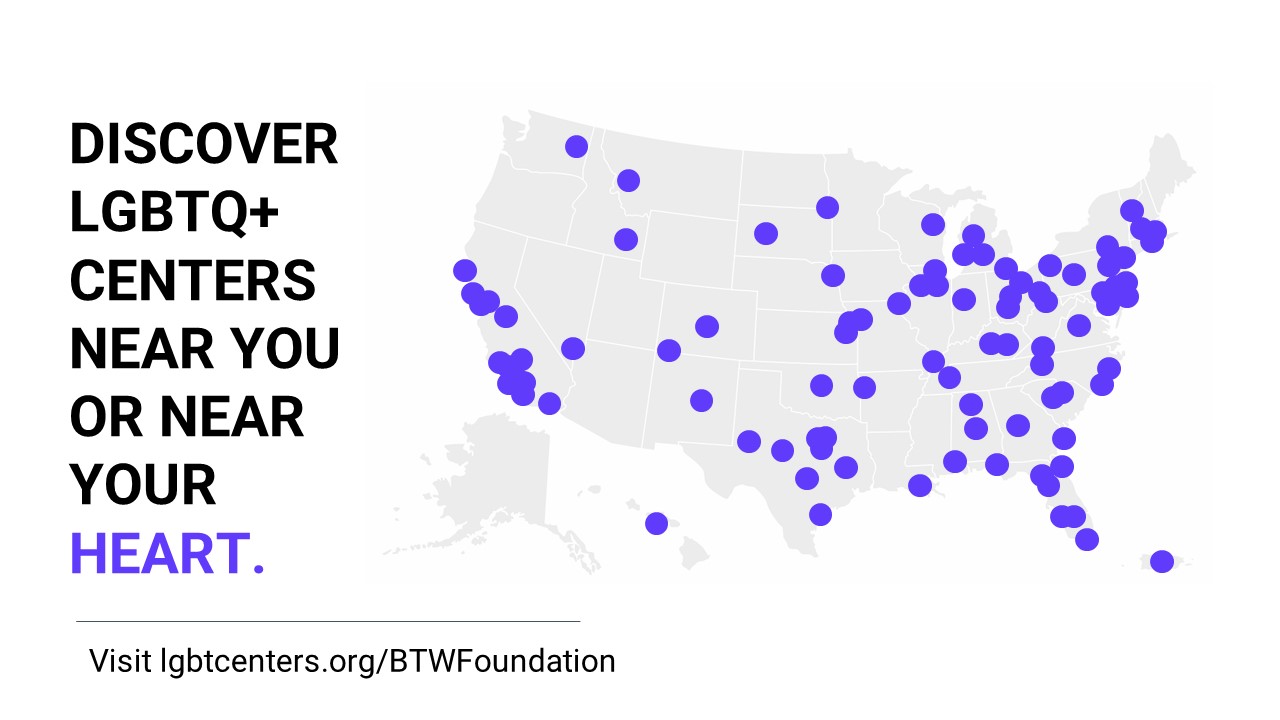

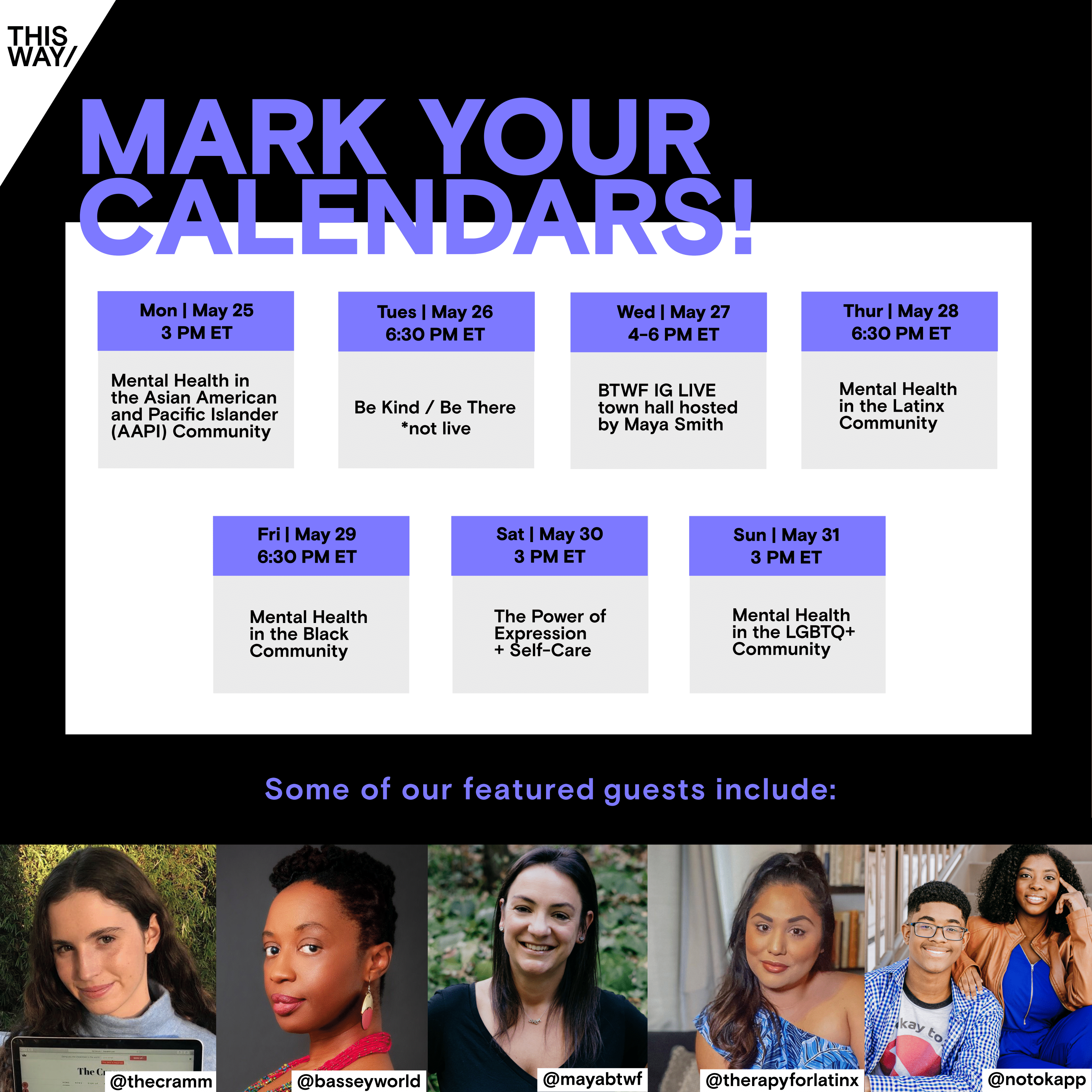

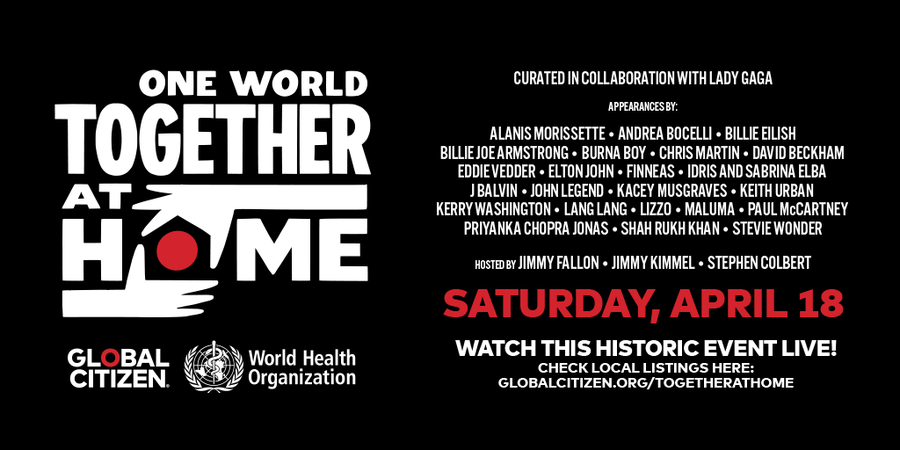

For more information, please visit:

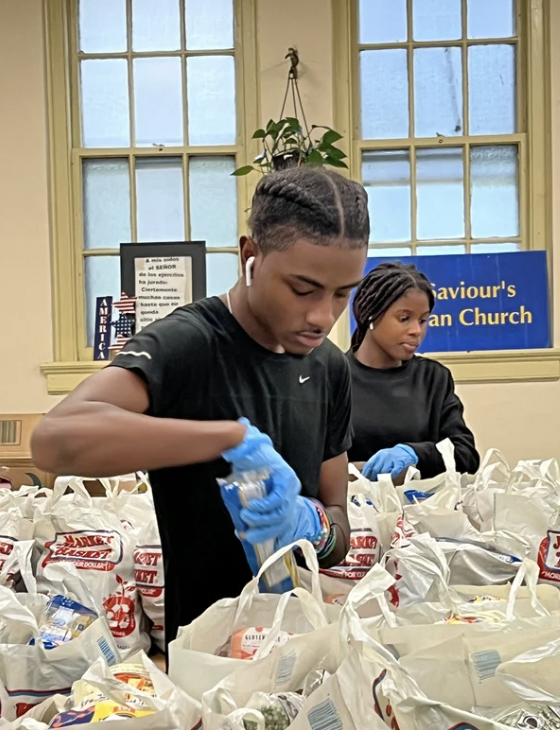

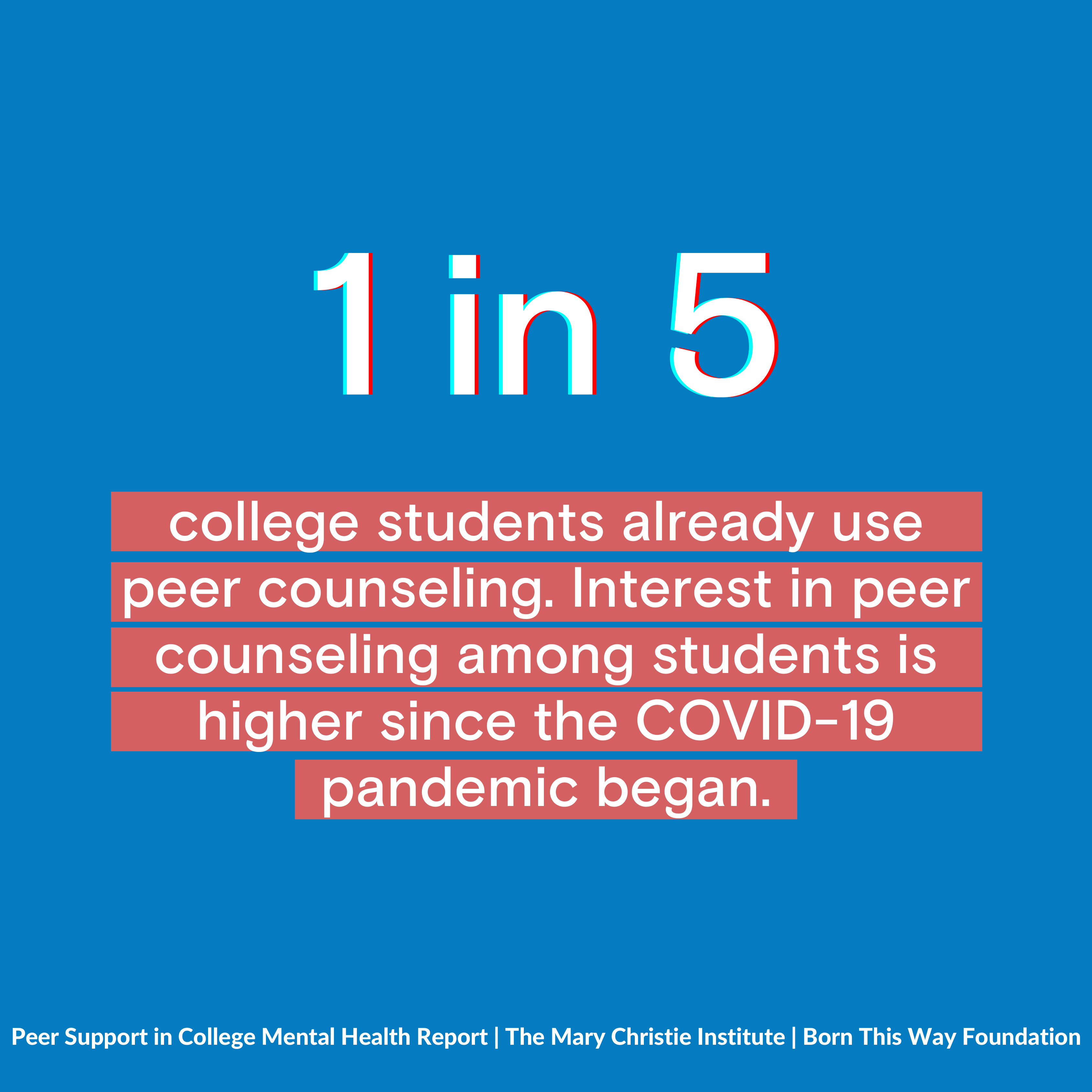

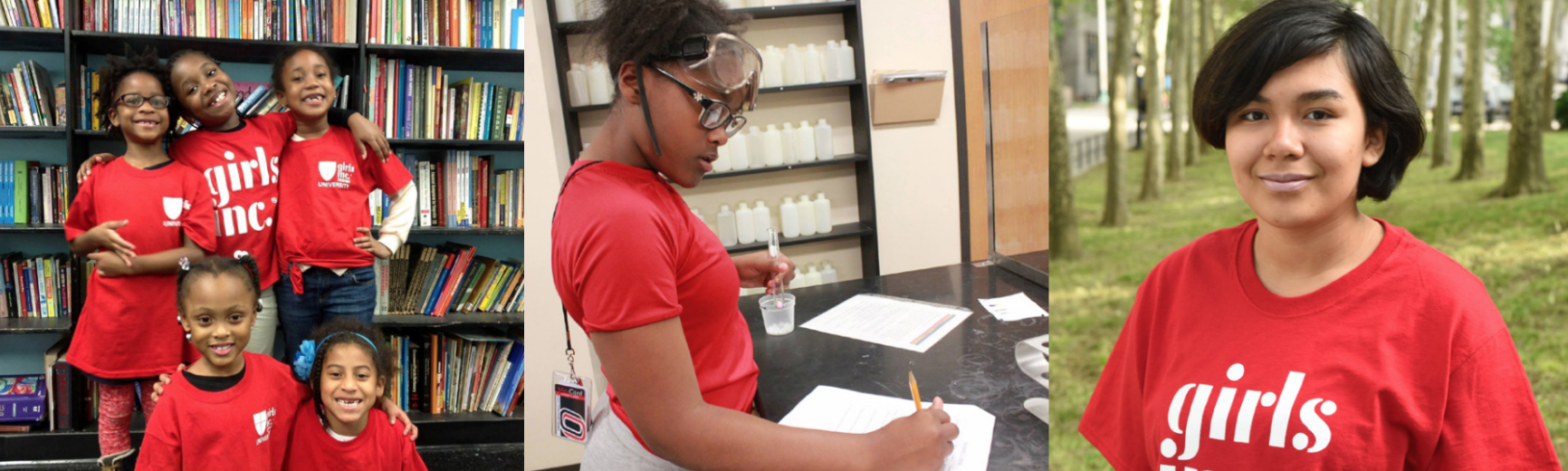

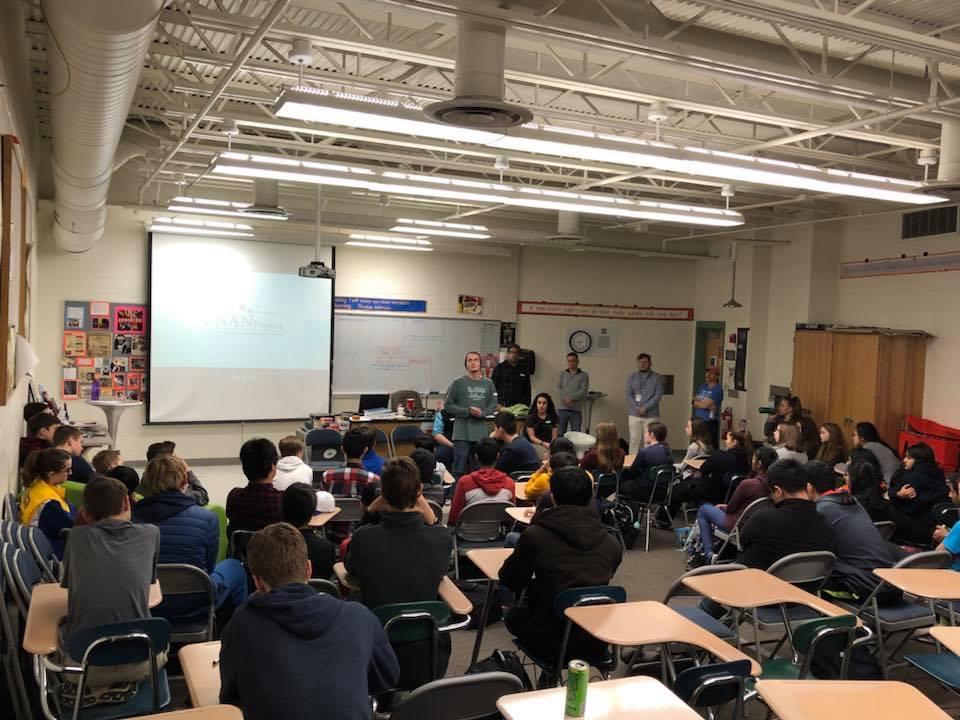

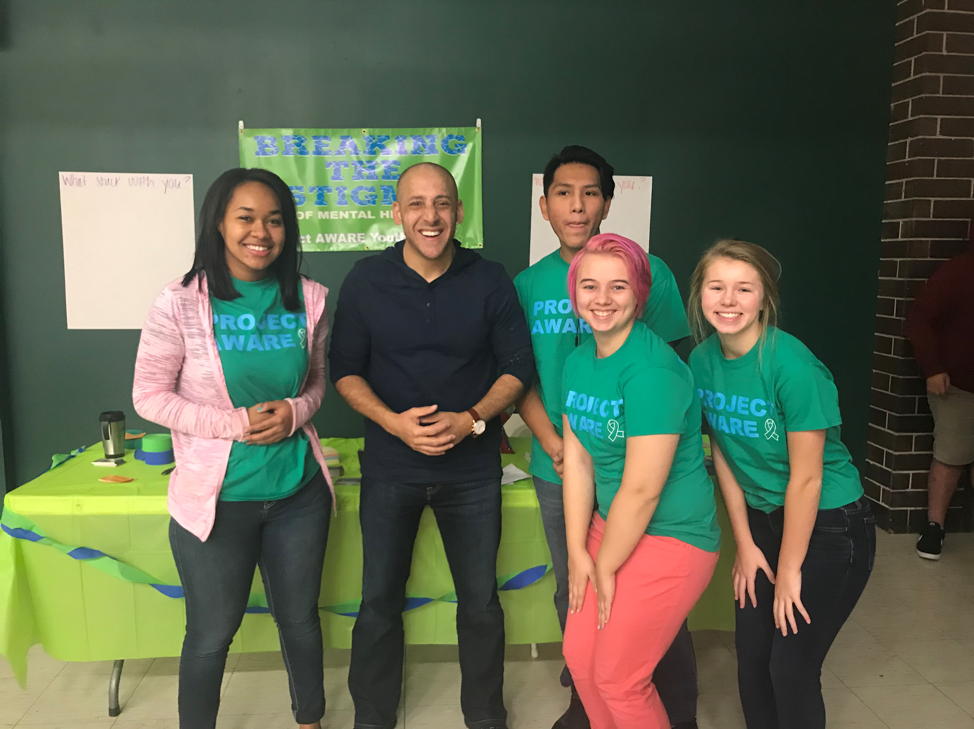

The Reflect Organization — An organization created with the goal of fostering open discussion about mental health and how we can bring about change in the culture of college campuses.

Active Minds — A national nonprofit that has chapters in schools all across the country. It is dedicated to advocating for mental health in college campuses.

The Princeton Perspective Project — An initiative started at Princeton University that brings perspective to student struggles and setbacks.

Penn Faces — An initiative started at Penn that emphasizes personal stories about “Penn Face” and how we can work to combat it.